Aerobatic superstar Sean D. Tucker will be inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame on July 19.

By Di Freeze

Sean D. Tucker hates talking about himself. What the charismatic aerobatic superstar—who will soon be inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame for his accomplishments—does like to talk about, is flying. On one particular morning, two weeks before his birthday (April 27), he explains why he was so caught up with thinking about flight that he forgot a scheduled interview.

“After I fly, I start thinking about the whole process, mentally critiquing,” he says after profusely apologizing. “So, I got on my bicycle and I started riding. About two miles into the ride, I’m thinking, ‘Uh, oh.'”

The scenery in the Monterey Bay area, where he lives, is perfect for a long, reflective bike ride.

“I go mountain biking up in the hills five or six days a week when I’m home,” he said.

Tucker explains that his air show performances require him to be as fit as possible, and to practice, practice, practice.

“It’s just part of the regime, especially on this level of flying,” he said. “I practice three times a day. Handling the G-forces constantly is really hard on the body. The fitter you are, the better you can withstand the G’s; but also, the fitter you are the better recovery you have from injury. Because you’re constantly injuring yourself—throwing your neck out, throwing your lower back out, pulling a muscle. It’s really tough in terms of how you have to breathe, what your body’s going through—high negative, high positive, high negative, high positive—and to do it close to the ground, you need to be very technical. The only way you can be that technical is through practice, so you’re always beating yourself up to make sure you can do it safely.”

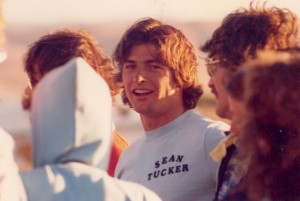

Sean Tucker, the second oldest of seven children, recalls that his father, who would become an aviation trial lawyer, often took the family for outings at Meadowlark Airport by Huntington Beach. “We’d watch airplanes land for hours and hours,” he said.

Tucker’s strenuous regime, which includes weightlifting, seems a little overwhelming to some of his friends.

“People think I’m weird,” he admits. “Since I’m home, yesterday, after practicing three times, I got to walk 18 holes with my buds. About 5:00, they say, ‘Want a beer?’ I say, “No, I gotta go to the gym.’ Because I spent four hours golfing, I got behind the power curve, and I had to go get my massage. You have to make a commitment to this stuff.”

Tucker, who has exercised six days a week for as long as he can remember, says he’s gotten more fanatical as he’s gotten older.

“I’m realizing how important it is,” he said. “In your 20s and 30s, you can recover easily. Eleven years ago, when I was 44, I broke open two vertebrate doing high negative G’s in aerobatics. I thought it was career ending. I was very lucky to find the right docs. We didn’t do surgery; we did some cortisone, but to actually have it totally healed, be pain-free, was a year and a half. That was a real wake-up call to me, as to how fit I need to be to play this game. When you’re young, your body can adapt. As you get older, you have to make a conscious effort to keep your body young, in terms of diet, exercise, the proper amount of rest. If you don’t, you can’t play the game. And I looooove the game. I looooove the flying.”

Compelled to the sky

Physically active since childhood, Sean Tucker exercises five or six days a week to stay fit for his performances. He practices his routines three times a day.

Tucker, born in 1952 in California, credits his dad for introducing him to flying. His father was a pilot, but he laughs and says he wasn’t necessarily a “good one.”

“I mentioned that in a Reader’s Digest article last year,” he said. “My poor mom; she really thought my dad was a great pilot. He was a great lawyer who had a tremendous amount of love for flying.”

Tucker recalls that although they had very little money, their hard-working father found pleasant pastimes for him and his siblings.

“As a family, we’d go to the beach and have picnics out at Meadowlark Airport by Huntington Beach,” he said. “We’d just watch airplanes land for hours and hours and hours.”

Once Mr. Tucker became an aviation trial lawyer, he started taking flying lessons.

“He really had to learn how to fly then,” Tucker said. “He got his instrument and his multi, but because he was representing the aircraft manufacturers in crashes, I think he was scared, too. I remember him sitting in the airplane; it would be cool, in the fog, and he’d be pouring down sweat.”

During high school, Tucker began working for his father as a file clerk.

“When nobody was looking, I’d sneak in and look at all the aircraft wrecks,” he laughed. “It’s pretty cool until you see a body in there, and then you really get freaked out.”

Sean Tucker tried skydiving a handful of times but quit when a friend died on his first jump. After conquering his fear by getting a pilot’s license and taking aerobatic lessons, he took up skydiving again, jumping 500 times to “make sure he could do it.”

Because of his mother constantly bringing up crashes, and his father, who died eight years ago, defending them, Tucker was a “very fearful flyer.” Still, he went up with his dad when he was in his early teens.

“Something really compelled me to the sky,” he said. “I just wanted to be there. I remember that first flight. It was dark in the morning, and then we poked through the overcast in the L.A. basin. The sun was just coming up over the High Sierras. I’ve never been closer to God in my whole life. It was awesome. Flying machines mesmerize me to this day.”

Tucker recalls that his father rented a Comanche.

“He also built a Volksplane, but it never flew,” he laughed.

He wasn’t the only sibling who took to the sky.

“My brother Bill is an air rescue helicopter pilot,” he said. “I’m the second oldest of seven kids and he’s the youngest.”

Conquering fear

While attending UC Santa Cruz, Sean became interested in crop-dusting. He loaded for a group of World War II veterans, got the opportunity to fly a Stearman and sprayed his first field in 1978. He later bought a helicopter for his crop-dusting business.

Tucker said that before he decided to take flying lessons, he attempted to delve into the world of skydiving.

“When I was 17, a friend of mine talked me into going skydiving,” he said. “We were going to do it as a father/son thing, but my dad chickened out. I went and I liked it, but it scared me. I had seven jumps, and I talked another friend into it; on his first jump, he died. At that time, it was static line controls. He panicked and wrapped himself in the chute before it opened, when he was falling through the sky. After seeing that, I didn’t want to be a skydiver anymore.”

Still, Tucker didn’t abandon the sky.

“I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll just try flying,'” he said. “But what I learned from my father, in terms of being a scaredy-cat, kind of got into my DNA. Facing that fear was tough.”

Tucker said that when he decided to work at getting a private license, fear made him dangerous.

Sean Tucker flew his first air show in 1976. Initially, he flew four or five shows a year, while he continued to crop-dust and do whatever else he could to “fly airplanes.”

“I knew I would go into a full-scale panic attack and freeze at the controls if there was ever an emergency,” he said. “If I even stalled the airplane or banked it over 30 degrees, I would freeze. I really shouldn’t have passed my check ride. I just lucked out. The guy blinked when I was recovering from a power-on stall, when my eyes were probably closed. It was that bad.”

To conquer his fear, Tucker took aerobatic lessons with Amelia Reid in San Jose, Calif., at Reid-Hillview Airport (RHV).

“I was always honest about my emotion,” he said. “I told her I was scared to death. She said, ‘Let’s work on it, talk about it.’ We talked about rolling an airplane. I thought I was going to have a heart attack when she was getting ready to do it. We rolled it, she let me roll it, and the rest is history. The airplane didn’t fall out of the sky, didn’t spin in, didn’t do anything dangerous. It was totally under control. That’s when I fell in love with it. I had 55 hours as a freshly new private pilot, and I didn’t want to do anything else but learn that art form.”

Tucker continues to be enamored with the art form.

“Probably even more so, because I understand it more—why I get to do it—than when I first began,” he said. “I’m more excited about the opportunity now—every opportunity. Like this morning’s flight. We practice as if it’s a performance. And when we’re at a performance, it’s just a practice setting, with all the incumbent emotions about sharing the magic and trying to provoke and inspire people.”

Tucker says this art form is the “third dimension.”

“On the ground, people are used to the x-axis and the y-axis,” he said. “That’s how they think of things. People walk straight or they turn left or right, or go backwards. But to go up, you have to go in the z-axis. Air show pilots are on the z-axis. The better you can perform and choreograph a sequence on the z-axis that people resonate with, the more powerful are the performances. That’s the coolest part: learning the z, baby!”

Jumping in

In 1979, Sean Tucker had to bail out of his S-2A. At the time, he was attempting to beat the existing record of 13 inverted flat spins, held by Art School. Tucker did 45, but then couldn’t recover.

Once Tucker had taken his aerobatic course, he decided to face skydiving again.

“I jumped 500 times, to make sure I could do it,” he said. “How I got into it was a sad story, but your experiences are what mold and shape you. Fear is one of the most powerful emotions there is. When you conquer that fear, you become stronger. I fell in love with what I was afraid of, and that’s how I faced myself. So it was a good thing in the end.”

Tucker’s 10-hour aerobatic course provided him with a certificate he cherishes to this day.

“When I could successfully loop, spin and roll, and land a tail dragger, I could solo the airplane,” he said. “I got a little card that said I was an aerobatic pilot. It was the best card I ever had. I was so proud of that.”

Tucker said he did everything he could to get money to fly.

“I’d beg, borrow and steal, and I got student loans, and just did nothing but fly those airplanes,” he said.

A weld break in flight forced Sean Tucker to bail out of his S-1C, which had replaced his S-2A. In 1985, he acquired an S-2S.

In 1973, while attending junior college in Santa Cruz, Tucker put up ads to take people on aerobatic thrill rides.

“I started a business called Tucker’s Freeflying Service. I put ads on campuses,” he said. “I was really busy. I was looking to cover the cost of the aircraft, so I could keep building time and experience. While I was going to college, I put on 900 hours in a Citabria from Amelia in two years.”

Traveling to a different beat

Although Tucker went to UC Santa Cruz with the aim of being a lawyer, he said that didn’t quite work out.

“I was supposed to be a lawyer because that’s what my dad was,” he said. “Instead, I went to work for crop-dusters.”

Tucker enjoyed loading for this group of men who were “larger than life.”

“I fell in love with these World War II guys and the way they fly,” he said.

Tucker was four classes away from graduating with a sociology degree when he had an opportunity to fly a Stearman.

“I said, ‘That’s what I’m going to do,'” he recalled. “My parents were a little disappointed, but by that time, they knew I was travelling to a different beat of the drummer.”

After becoming the U.S. National Advanced Aerobatic Champion in 1988, Sean Tucker committed himself seriously to being a full-time air show flyer. In those days, while unsponsored, he performed in more than 30 air shows a year.

Tucker didn’t spray his first field until 1978. By then, he’d already flown his first air show and gotten married. Tucker said that since he’d participated in his first show in 1976, a year before he got married, it wasn’t a surprise to his new in-laws.

“Colleen’s parents couldn’t say anything—that’s this guy’s a wacko,” he laughed. “They didn’t put odds that we’d make it, though.”

Tucker said that making money crop-dusting interrupted his “bad habit of aerobatic flight.” But, looking back, he confessed that he hadn’t yet gotten to the point of being a very good air show pilot.

“I had a lot of passion, but I was still pretty dangerous,” he said. “We weren’t making much money flying these shows—$500 here, $1,000 there. I wasn’t on the circuit; I flew four or five shows a year—California, a couple in Mexico—and worked for the crop-dusters. I hadn’t started spraying yet. I was bartending and waiting tables, doing anything I could to fly airplanes. But the old guys in those days used to tell me, ‘Sean, you’re a little too wild. You have to settle down.’ I used to think, ‘What do these gray-haired guys know? They’re just chicken!'”

Abusing flying privileges

Tucker fondly recalls his first airplane, a Pitts S-2A.

“I bought it from Curtis Pitts,” he said. “He was a good friend of mine, and I really respected him. Every biplane I own, no matter how highly modified it is, is always going to be called a Pitts. These are custom built. We buy parts from the Pitts factory—a few here and there—but they’re far from factory-built Pitts.”

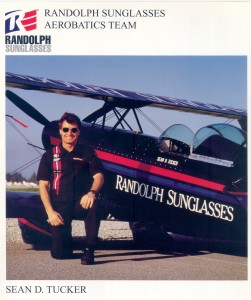

After being on the air show circuit for three or four years, Sean Tucker got his first national sponsorship: Randolph Sunglasses.

In 1979, after “abusing” his flying privileges, Tucker had to bail out of his S-2A.

“I call that the crash of ’79,” he laughed. “Some guy at some backcountry air show in Dos Palos, Calif., was going to pay me $500 to do 30 inverted flat spins. The most anybody had done was Art Scholl; he did 13. I made 30. Then I made 40. At 45, I was going to hit the ground, because I couldn’t recover from the inverted flat spins. I got the center of gravity so far out, because I was leaning so far outside the airplane, that my feet couldn’t reach the pedal to stop the spin.”

Tucker said that after that day, he looked at his future and it wasn’t very good.

“I was just starting to make some money crop-dusting,” he said. “Colleen didn’t think I had much of a future air show flying, so I took the insurance money, and after I paid off the bank, I put a down payment on a helicopter. I knew that at least I could support my family crop-dusting on the helicopter.”

For a while, Tucker didn’t buy another aerobatic airplane.

“I had to support a family and buy a house before I could go live my dream again, because I made a commitment to another human being,” he said.

When he decided it was time to re-enter the arena, he bought a Pitts S-1C from a crop-duster in Maryland.

“It had a pretty paint job, but it was poorly constructed and had some bad welds,” he said. “I was flying it too hard. I jumped out of that airplane when a weld broke.”

I’m good enough

The sponsorship of Randolph Sunglasses of about $150,000 allowed Sean Tucker to support his family and be a full-time professional.

A year later, in 1985, Tucker spent $32,000 on an S-2S.

“After the second one, I knew I wasn’t going to buy a homebuilt airplane, and I was going to look over every weld,” he laughed. “In those days, you could afford to get a loan and buy these airplanes. A regular guy could afford to have that dream. I bought my first one, brand new, for $23,000. I bought the second one, the bad one, for $18,000. Now, my show machine is worth $350,000.”

After buying the S-2S, Tucker informed Wayne Handley, an air show performer he worked with who also had a Pitts, that he was going to enter an aerobatic competition.

“I told him I was going to do this competition to learn how to do it right, to be mentored properly and also get a trophy,” he said. “Once you get a trophy, you have a credential.”

Tucker worked earnestly, becoming the U.S. National Advanced Aerobatic Champion in 1988.

“I got my trophy and put it on a brochure,” he said. “I went to ICAS—the International Council of Air Shows—and said, ‘OK, I have a trophy; I’m good enough.’ That’s when I started seriously committing to being a full-time air show flyer.”

In those days, Tucker performed in more than 30 air shows a year.

“I wasn’t sponsored, and it took that much to make it pay for itself when I was still crop-dusting full time,” he said.

The first sponsorship Tucker obtained was from Lycoming, which agreed to be his engine sponsor.

“It really helped when I started getting a free engine every year, instead of spending $35,000 building one,” he said. “I had only been on the air show circuit for three or four years when I got my first national sponsorship; that’s a short amount of time.”

The sponsorship of Randolph Sunglasses of about $150,000 allowed him to support his family.

“I could be a full-time professional,” he said. “I could keep striving to perfection, to learning this art form. It allowed me to really take a leave of absence from my helicopter company and not be a burden, to where they had to pay my salary.”

Randolph Sunglasses sponsored him for a couple of years, followed by MCI.

“MCI came along, and that was $350,000, and then it got up to $650,000,” he recalled. “I was with them for four years.”

Tucker said the timing couldn’t have been better for his next sponsor, Oracle Corporation.

“I was just finishing up with MCI,” he said. “Oracle had sponsored Wayne Handley, but he had a crash a couple years prior. Larry Ellison still wanted to do something in the air show business. He’s a pilot and he really liked it. He had his pilot contact me. He said, ‘Send me a one-page proposal.’ I did, and he said, ‘I want to do it.’ That’s how it all started, and we haven’t looked back since.”

Saying good-bye

After being sponsored by Randolph Sunglasses for a couple of years, Sean Tucker developed a partnership with MCI that lasted about four years.

In 1992, Tucker became the first aerobatic performer to receive the Art Scholl Memorial Showmanship Award and the Bill Barber Award for Air Show Showmanship—the two most prestigious awards in the air show industry—in the same year. Four years later, in 1996, he bought an aircraft he would fly for the next 10 years.

His awards in that decade included the 1997 General Aviation News and Flyer Reader’s Choice Award for Best Male Performer; Undefeated Champion of the Championship Airshow Pilots Association Challenge, 1998-2001; International Council of Airshows Sword of Excellence and World Airshow Federation Champion, 2000; and induction into the USAF Gathering of Eagles, 2001. In 2003, the National Air & Space Smithsonian named him one of the 25 “Living Legends of Flight.”

He explained the process that resulted in the aircraft he flew to stardom: the Oracle Challenger.

“First, you start with something that works and then you start adding on,” he said. “The Pitts design was a great design. I’m the flying guy. I’m not the smart guy, but I have access to some of the best. The effort’s a collaboration of some great designers, great builders, and I get my input as a flyer.

“Steve Wolf, one of the finest aircraft builders in the world, built my wings. I have eight ailerons on them (instead of the traditional four). Steve conferred with Curtis Pitts on it. Steve also did the windscreen. Delmar Benjamin, who built the Gee Bee, designed the cowling. We kept changing and modifying the tail; that was from Eddie Sauerman.”

The tail on the airplane was modeled after the tail used on high-performance remote control airplanes. The job of making the plane constantly better and faster goes to his quality assurance person.

“The goal was to have this biplane have just as much performance as the new state-of-the-art monoplanes,” he said. “I still love the romance, the fabric of the biplane. People know when they see a biplane at an air show that it’s supposed to be there. It harkens back to the old barnstorming days.”

A 380-hp Lycoming engine turning a Hartzell three-blade propeller powered the 1,129-lb. Oracle Challenger, capable of a top speed of 300 and flying backwards at 100. Tucker was measured so the plane could be built around him. The skin was composed of lightweight fabric similar to sail cloth, allowing Tucker to feel the wind. The biplanes’ wings were wired for smoke generators and pyrotechnics. A camera that could be mounted on any of the four wingtips provided a bird’s eye view of the pilot’s aerobatic maneuvers.

His intense “Sky Dances” required that the engine and wings be rebuilt at the end of each season. Tucker said the Oracle Challenger was just getting broken in when he had mechanical trouble on the way to Sun ‘n Fun in April 2006.

“When I’m transiting my own airplane, I still practice twice a day,” he said. “We stopped to see my friend, out in the middle of nowhere. His airport is in Kasada, Red River Parish, Louisiana. We spent the night there. We were going to stay there the whole day so I could practice, because we weren’t planning to go to Sun-n-Fun until the next day.”

Tucker recalls that he was practicing 10 to 15 feet off the ground, over a swamp area, when he had a mechanical failure.

“I lost control of the aircraft at 225 miles and 7.4 G’s pull,” he said. “That’s a moment when you know you’re instantly dead. It’s a horrible, weird feeling, to know you’re dead. That’s the first thought: ‘I am going to die. I am dead.’ ”

But Tucker was fortunate that the problem happened while in a pull.

“The airplane was going up, but it was porpoising up and down,” he said. “I had no elevator control, and then the tail would make it go down, up and down. The stick wasn’t working anymore, so I decided to try to fly it with the trim. On that Pitts, a little bar on the side of the fuselage controls the trim tab. Once I knew I wasn’t in imminent peril, I grabbed a hold of the trim tab. By flying it with the trim, it kept going up, and then I knew, ‘OK, I’m not going to die immediately.'”

As Sean Tucker was finishing his commitments to MCI, Oracle approached him. Tucker and Larry Ellison made an agreement, leading to a long-term relationship that continues today.

Once he got through 1,000 feet, he was able to breathe a sigh of relief.

“I thought, ‘At least I have a shot at living now,'” he remembered. “I checked my fuel and called my team. I told them just to be quiet so I could think about trying to see if I could land, because I didn’t want to kill the airplane. Ten years and a million bucks in that thing; I loved that piece of equipment! It was the finest flying machine I’ve ever flown in my life—with so much tender love and care. I had already jumped out of two previous ones; I know what that feels like. That’s not fun.”

Tucker’s intent was to try to slow the aircraft down.

“I was trying to manage the controls to where I could get it in a three-point attitude, so I could land it with the rudders and the trim tab and a little bit of power,” he said. “Soon as I slowed down enough, nose just right, it’d immediately take another dive. It would gain four miles an hour, and it would do it on its own; I’d lose control of it.”

After 12 to 15 minutes of that, Tucker knew it wasn’t going to work.

“I knew I had to let her go,” he said. “Brian Norris, my operations coordinator, got the sheriff and coroner out there. We closed some roads. Then, we were just trying to figure out where I would jump out of this airplane. The last thing I wanted to do was jump out and have the airplane land on some poor guy’s pickup truck, after he just got a raise and got a diamond ring and asked his girl to marry him.”

According to Sean Tucker, the Oracle Challenger is a collaboration of some great designers and builders, but he gets his input as a flyer. “The goal was to have this biplane have just as much performance as the new state-of-the-art monoplanes,” he said.

After being directed to a certain farmer’s field, Tucker headed in that direction.

“I found the field,” he said. “Initially, I took it up to 9,000 feet, thinking I’d jump from high to give me more time. But then I couldn’t visualize where the airplane would crash. So I took it back down to 5,000 feet. I knew what the airplane would do when I let go of it and how it would go into a spiral. I sensed where it would go.”

When he finally got down to three gallons of gas, it was time.

“I set it up,” he said. “I was on the radio with my crew, so I said, ‘Listen, if anything happens to me, tell Colleen, Eric and Tara I love them.'”

To be continued in the August issue.