By Terry Stephens

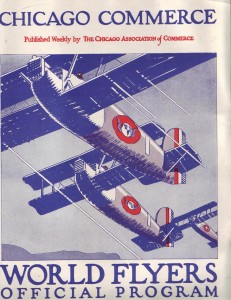

Douglas World Cruisers, flown by U.S. Army Air Service pilots, prepare to leave Seattle to make the first flight around the globe.

Seattle pilot Bob Dempster, inspired by the globe-circling flight of two U.S. Army Air Service planes 84 years ago, plans to duplicate their 175-day, 23,942-nautical mile journey. He’s even building his own Douglas World Cruiser to make the flight.

“Deciding to recreate that trip wasn’t an epiphany moment,” Dempster said. “The decision came from my love of flying and my admiration for those aviators who were the first to circumnavigate the earth by air. I particularly want to finish the flight that the Seattle began. That’s why my plane is the Seattle II.”

On April 6, 1924, four Douglas DT torpedo bombers, modified with extra fuel tanks and carrying the World Cruiser designation, took off from Seattle’s Sand Point Aviation Field bound for Alaska. The pilots of planes named for the cities of Seattle, Boston, Chicago and New Orleans found conditions were, at times, tougher than they anticipated.

“Eventually, two of them made it, but there was nothing easy about it,” Dempster said. “Flying over the Aleutian Islands, the Seattle crashed on an Alaskan mountain during a blinding snowstorm. Fortunately, the two-man crew survived and plodded through miles of wilderness to safety.”

The three remaining planes flew on, cruising at 78 mph across Asia, the Middle East and Europe, before rough weather forced the Boston down as the three planes crossed the Atlantic. The last photo taken of the Boston shows it upside down, tail in the air and sinking. Fortunately, Dempster said, the U.S. Navy cruiser USS Richmond, one of the ships stationed as a precaution along the pilots’ water route, was able to rescue the crew.

Four of these World Cruisers left Seattle for the global adventure, but only two completed the record flight.

Finally, two of the open-cockpit biplanes, Chicago and New Orleans, reached the U.S. for a rendezvous with the fifth Douglas Cruiser, built as a spare plane for the adventure. The three planes continued across the country, landing at Sand Point on Sept. 28.

Despite losing two planes in the attempt, the completion of that record flight established Douglas Aircraft Co. as one of the world’s major aviation companies, an achievement reflected in the company’s new motto, “First Around the World – First the World Around.”

“The magnitude of that flight was as complex as America’s moon landing in 1969,” Dempster said. “Logistically, spare engines and other supplies had to be distributed around the world along the flight path. The engineering of the special planes, built for both wheels and floats, was amazing. So was the extensive crew training, cooperation between military services, global diplomatic support and the flying skill and determination of the eight men in the crews.”

Today, the record-setting flight that captured the world’s imagination has few reminders. One of the two planes that completed the global flight, Chicago, hangs in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C. In Santa Monica, Calif., where the famous planes were built, New Orleans most recently hung in the Museum of Flying. Today, its fabric is being restored in preparation for a place in the new Museum of Flying that will open in late 2009 at Santa Monica Municipal Airport (SMO).

Although Sand Point is no longer a municipal airfield, nor the naval air station it once was in the 1940s, a 1924 monument to the World Cruisers still stands, a granite obelisk topped by a pair of giant “angel” wings. A bronze commemorative plaque is also on display at Mere Point in Casco Bay, Maine, one of the points touched by the planes on their route. Another plaque remains on Attu, one of the Aleutian Islands. Artifacts from the record flight are scattered, from the USAF museum in Dayton, Ohio; to the Museum of Flight, Seattle; the Aviation Museum of Kentucky at Bluegrass Airport in Lexington; and at San Antonio’s History and Traditions Museum.

Dempters’ turn

Dempster said this trip won’t be an attempt to duplicate that journey in exacting detail.

“It’s more of a commemorative flight,” he said. “We’ll have some authentic flight instruments from that era. I already have a donated 1924 cockpit switch for the plane’s original 420-hp Liberty V-12 engine and a vintage altimeter. But we’re installing modern radio and avionics systems for our safety and also to comply with today’s global aviation requirements.”

In place of the original plane’s tailskid, he’s installing a wheel. He also added brakes for the main landing gear and strengthened the plane’s original metal tube frame with newer, stronger materials. Donated Edo metal floats with water rudders will replace the original rudderless wooden floats.

“We’ll be restoring a Liberty V-12 for the museum display, but our engine will be a much more reliable and modern design within the same range of 300 to 400 hp,” Dempster said. “We’ll use more durable, nonflammable material to cover the frame, because the original material was cotton. When it was wet, the fabric sagged and distorted the airfoil, as well as adding a lot of weight. Also, paints used on the cotton were highly flammable, so we want to avoid that potential problem.”

In 1990, Bob and Diane Dempster flew their Piper Super Cub from England to Egypt, as part of a short-lived attempt to fly to Australia.

Dempster has been working with a team of Federal Aviation Administration-certified mechanics and inspectors, assisted by commercial, experimental and antique aircraft restoration experts. For years, he’s been filling the World Cruiser Association’s website with photos and details of the construction progress, including making the frame, gluing fabric and creating a replica of the walnut steering wheel used on the Cruisers.

Dempster’s wife, Diane, has been deeply involved in the whole venture. A Seattle Boeing employee, she has a master’s degree in education and is working on her doctorate. Also a faculty member of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and a licensed pilot, she presides over the association’s programs for youth and college students, mentoring students about aviation as an education opportunity, recreation sport and career field.

The Dempsters also involved local Civil Aviation Patrol cadets in a Build-A-Rib program, teaching them about aerodynamics as they made a 7 foot, 6 inch long wing rib that became a part of the finished aircraft. Bob Dempster has made numerous presentations about the project to Experimental Aircraft Association chapters, as well as the Washington Pilots Association, Women in Education, Northwest Aviation Trade Expositions and various community groups. In recent years, he’s promoted his Seattle II venture at the annual Northwest Aviation Conference & Trade Show in Puyallup, Wash.

Today, the Seattle II’s final construction is taking place in a corner of Boeing’s Plant 2 in Seattle, where B-17s were built during World War II. It’s less than a year away from taking off for a flight into aviation history books.

“I’m planning the first test hop from Boeing Field by the end of the year,” he said. “Then we’ll start our world flight April 6, 2009, exactly 85 years after the original adventure. Other than preserving that date, we’ll just be flying to complete the trip, whatever it takes on whatever schedule. It’s a celebration flight, after all.”

Diane and Bob Dempster are building their own World Cruiser, a replica of the original planes that were the first to be flown around the world.

Along with passports, the Dempsters will need flight permits to enter each country, he said, adding that language barriers will be erased by English-speaking air controllers at international airports along the route, including across Russia and China.

The Dempsters are already accustomed to international flying. In 1990, they shipped their Piper J-3 Cub to England for a flight to Egypt and on to Australia. Crossing the desert, they were forced to make an emergency landing at an Egyptian air force base. An officer discouraged them from continuing the flight because of the 120-degree temperatures.

“He told us it really wasn’t a good time to make the trip, so we gave it up,” Dempster recalled. “We soon discovered it might not have been just the temperature he was warning us about. A week and a half after we left Egypt, the Persian Gulf War began.”

Support is building

For more than five years, the World Cruiser has been a seven-day-a-week project for Dempster, including taking time to educate people about the historic aviation event and raise money for his venture.

“Dream like you mean it!” he said. “I’m an optimist. If I were a realist, none of this would’ve happened. It’s a lot of work, but it will become an emotional moment at the top of the mountain when we get there. We’ve had a lot of magic moments on the way, too. But you always have to be your greatest critic and your own best cheerleader.”

In the early years, the Dempsters financed the project on their own.

“I spend like I mean it, too,” he said, laughing, “I just don’t add up the bills. To get it started, we financed it by refinancing our home and cars several times, paying off each loan and then borrowing on each item again. Diane works long hours with me, too, but she continues her employment at Boeing to provide for our living.”

Now, he’s finally getting broader support.

“Over the years, we’ve gotten the plane to a point where people really believe it’s going to happen,” he said. “Then, they’re willing to get on board. People like to invest in success.”

In his booth at the 2008 Northwest Aviation Conference in Puyallup, Wash., last February, Bob Dempster showed off the steering wheel he built for his 1924 World Cruiser replica.

Matching grants for the project have come from Boeing and IBM, along with sustaining membership donations from Harper Engineering and numerous individuals. Support has also come from The Royal Aeronautical Society, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History and Williams Machine & Fabrication in Seattle. The Boeing Employees Community Fund, Salmon Bay Boatworks, Seattle Museum of History and Industry, Seattle Maritime Historical Society, Replica Fighters Association, Seattle Museum of Flight and many other groups and individuals are helping the Dempsters fulfill this dream as well.

“On April 6, we put on a huge gala fundraising event at the Museum of Flight for 160 people,” Dempster said. “Many of them came from the Museum of Flight, including director Bonnie Dunbar, and from the Boeing Co., Pratt & Whitney and other corporate supporters. People are being inspired, because this isn’t only an aviation project, but also a community history project for Seattle.”

For Dempster, his pending flight plan is just another chapter in a life filled with flying fever.

“I grew up around flying,” he said. “My father learned to fly in World War II, came home and started giving flying lessons. He taught land and seaplane flying, plus multi-engine instruction, along with running a charter service in Syracuse, N.Y. I started out flying, then did other things for years, then wound up back in aviation. Now, it’s led me to this.”

Once the flight is complete, the Seattle II will be placed on display at the Museum of Flight.

For more information, visit [http://www.seattleworldcruiser.org].