By Greg Brown

“Need help?” yelled the guy in the boat.

“No thanks,” I replied, not daring to turn my head too far, for fear of falling into the water. We were adrift in the middle of the Colorado River, with me balanced precariously face down on the seaplane’s float, pumping water out of the forward float compartments. Twice we had tried to take off, unsuccessfully, given today’s calm wind and glassy waters.

“You must not have emptied all the water from the floats,” said examiner Joe La Placa. And then, “Get out there and do it again.”

“Great way to start a check ride,” I thought.

I was here to earn my single-engine seaplane rating from La Placa Flying Service at Lake Havasu City, Ariz. At that time, Joe and Jean La Placa trained seaplane pilots from all over the world—this in a state with just one natural lake and only four rivers that flow year-round. (These days, Joe limits his service primarily to single-engine land- and seaplane flight tests.)

My training began at a tiny cove on the river with no flight school and no ramp—just a faded-orange Cessna 150 on floats, forlornly perched atop a winch platform. Unlike normal 150s, this one features bracing behind the windshield and an electric fuel pump to ensure fuel flow at high-pitch attitudes. Between the seats is a handle for raising and lowering water rudders on the floats, and under the cowl lurks 150-hp, half again more than what originally came installed. Floatplanes are no speed demons—the oversized engine is required to get the airplane off the water.

Like boat hulls, seaplane floats accumulate water, and therefore must be pumped out before every flight. I was to become expert at this process, using a hand pump and one powered through the cigarette lighter receptacle.

“Drain the floats properly before leaving shore,” Joe counseled me, “because it’s a lot tougher in the middle of the lake.” (I would later learn the truth of this wisdom.)

We also checked the propeller for water erosion and cracks caused by spray, a problem so serious that wilderness seaplane pilots sometimes carry hacksaws in their survival gear, for removing damaged prop tips, if necessary, to reach a place where proper repairs can be made. Water flying often requires improvising where help is not available.

After preflight, I was surprised to see two-foot lengths of tie-down rope still hanging from the wings.

“Those show us which way the wind is blowing on the water,” explained Joe.

We zeroed the altimeter to mark the lake’s surface, and started the engine.

“No need to test the brakes,” observed Mr. La Placa with a smile.

As soon as the engine starts, you’re moving; there’s no ground resistance to hold you in place. With water rudders in the water, “idling taxi” proved surprisingly easy.

Next, I learned high-speed taxi “on the step,” which means hydroplaning like a speedboat. From there, it’s a simple matter to increase power and takeoff. Once in the air, flying was like a landplane, but more stable due to additional weight and lift from the floats.

It turns out that the biggest seaplane kick is flying low—really low. We spent almost all of our five flight hours within 500 feet of the water, including downwind for landings at 200 feet.

Height above water is tough to judge, especially under calm conditions, so for landing I learned to stabilize our approach for minimum descent rate, then wait for the plane to land itself—better touch down softly, as there are no springs on the floats. Mr. La Placa also taught me to skim the shoreline on final, so as to better “feel” the level of the lake surface ahead. For “short field” practice, we landed in a postcard-pretty cove and beached the airplane for a break.

Lengths of tie-down rope are left dangling from the wings to show wind direction when the plane is stationary on the water.

By the time I was to take my recommendation ride with instructor Barry Grant, I felt like pretty hot stuff; my takeoffs and landings were going great. But I inadvertently “plow taxied” back to shore, slogging nose-high through the water with lots of power, without getting “on the step.” You’re not supposed to do that, Joe chided me upon return, because it consumes fuel, erodes the prop, and accumulates water in the floats.

Worse yet, I apparently didn’t get all that water out prior to the check ride, leading to our takeoff debacle. If only that tour boat hadn’t come by—me bent over the pump with my butt in the air, and all those people waving! Fortunately my efforts paid off and we took to the air, the rest of the check ride being so much fun that my embarrassment was quickly forgotten.

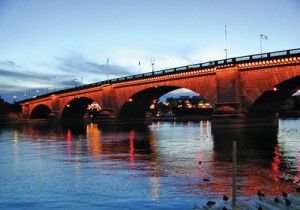

Along with air work and water maneuvers, we flew the rugged Colorado River north to Needles, Calif., traversing massive marshes and ancient Indian glyphs along the way. Best of all was craggy Topock Gorge, its tumbled peaks cast aside, as if by ancient gods playing in red clay. Upon return, Jean La Placa greeted us with completed paperwork, sweet home-grown tangerines, and a smile to match. We winched the plane out of the water, and suddenly it was over.

All too soon I was winging my way homeward aboard the “Flying Carpet,” with rich images of sun and spray captivating my mind, as they would for days to come. When learning something new, no matter how many others may have preceded you, there’s a bit of pioneering associated with it. The popular TV slogan notwithstanding, all it really takes for adventure is to boldly go where you have never gone before. Flying gives us that opportunity time after time.

Skimming gracefully over blue waters at 200 feet—wow! I’m still dreaming about it.

Author of numerous books and articles, Greg Brown is a columnist for AOPA Flight Training magazine. Read more of his tales in “Flying Carpet: The Soul of an Airplane,” available through your favorite bookstore, pilot shop, or online catalog, and visit [http://www.gregbrownflyingcarpet.com].

- Joe La Placa shares pre-takeoff pointers.

- We flew the Colorado River through craggy Topock Gorge, its tumbled peaks cast aside as if by ancient gods playing in red clay.

- The La Placas also operate a rare “Twin Bee” amphibian, a design derivative of the single-engine Republic Seabee.