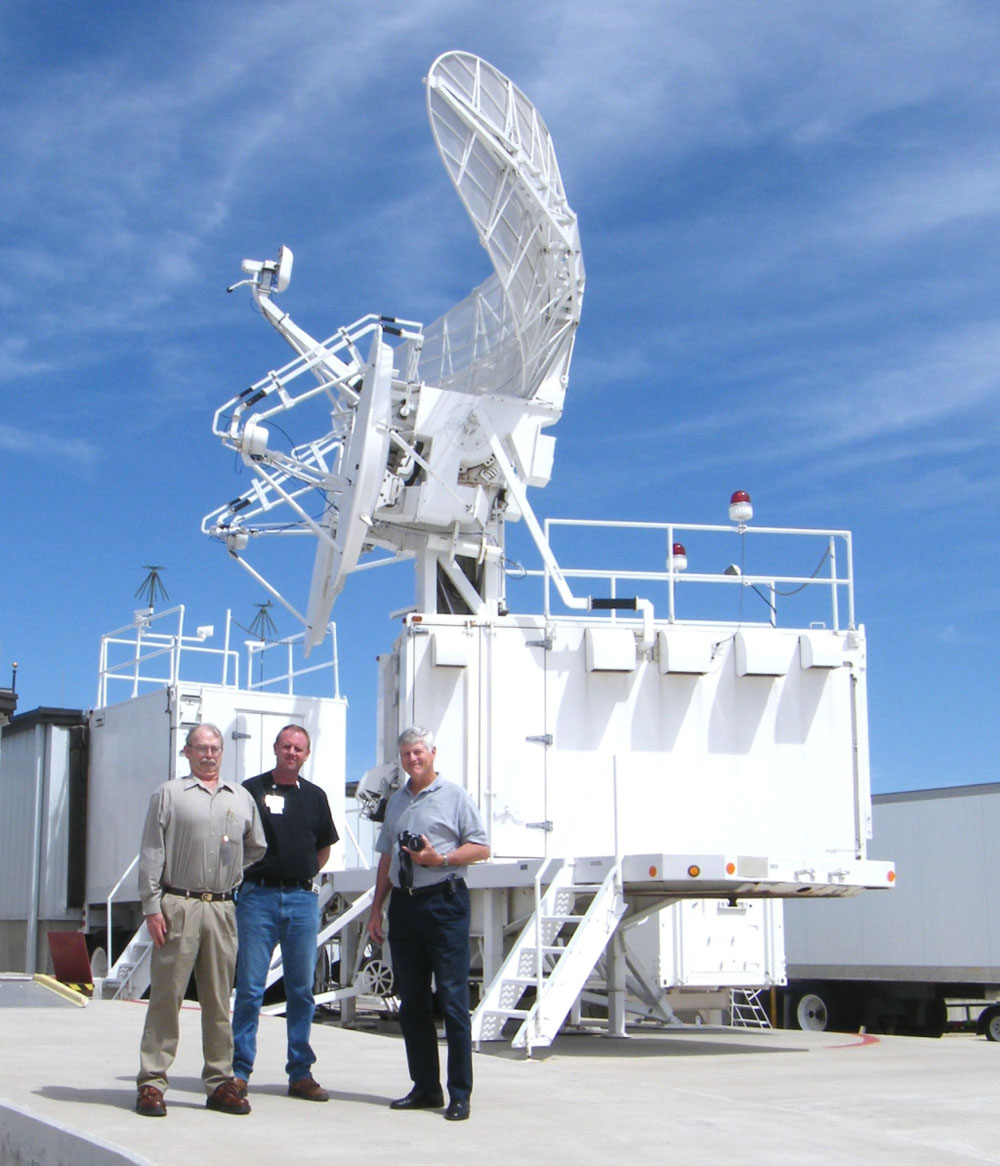

L to R: the MUTES radar antenna dwarfs ESS site manager Bill Clingenpeel, a radar technician and airspace manager Dwight Williams.

By J Carpenter

The Snyder Electronic Scoring Site, established in 2002 at Winston Field Airport (SNK) in Snyder, Texas, provides “real world” airpower threat-reaction training to U.S. Air Force aircrews to help ensure the survivability of personnel and equipment in actual battle.

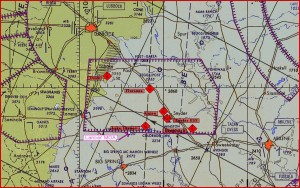

Pilots are familiar with military operation areas—airspaces provided by the federal government to allow military pilot training in various aircraft. The Lancer MOA is located in West Texas between Abilene and Lubbock. The space measures approximately 3,200 square miles, begins at 6,500 feet above mean sea level and extends upward to 40,000 feet. The primary customers of the Lancer MOA consist of B-52 aircrews of the 2nd Bomb Wing from Barksdale Air Force Base in Bossier City, La., and B-1B aircrews of the 7th Bomb Wing from Dyess AFB in nearby Abilene. Training aircraft, like the F-15 fighter and the EC-130 transport plane, also use the airspace.

Dwight M. Williams is the airspace manager for the 7th Bomber Wing. In a rare civilian tour, Williams explained the concept and procedures of the Snyder ESS. The facility, located on the grounds of SNK, is comprised of a 7,000-square-foot main building plus several adjacent radar devices, all surrounded by a high-security fence on 15 acres of land. In addition, several remote radar emitters are located on private ranches within the MOA. Twenty-three contract employees and two government liaison employees work various shifts at the installation. The Snyder ESS provided electronic combat training for 1,295 sortie operations in 2007.

Williams said that the Lancer MOA is located directly above the city of Snyder while other nearby airports are on the periphery of the airspace. That’s why Snyder is the site for the ESS facility. Also, the infrastructure of the city provided an adequate amount of land at its airport.

“The city was very cooperative in helping to establish the facility,” Williams said.

The ESS did cite one problem, though—the facility had inadequate water pressure. The city provided a pumping station at a cost of more than $15,000.

“They did that out of their own pocket, and we were very appreciative,” Williams said. “It’s a pretty neat deal. We bring approximately $1.2 million into the local economy.”

Equipment units that make up the ESS include the multiple threat emitter system, the smaller remote Mini-MUTES, the threat reaction analysis indicator system, the route instrumentation integration system and the integrated tactics assessment system.

MUTES are transmitters with large dish antennas that send out multiple frequency signals to the bombers flying above. Mini-MUTES are smaller sending units spread out in remote locations within the Lancer MOA. Both systems, 20 in all, transmit signals that are interpreted by bombers as antiaircraft weapons, surface-to-air missiles and tracking radar.

TRAINS are receiver-analyzer devices that collect and evaluate the aircraft’s response to the signals sent by the MUTES. TRAINS can also cause MUTES to react to the aircraft’s reactions.

RIIS is a personal computer-based system that collects data from all the emitters and systems used during the training sortie. The PC transmits this information to the RIIS Operations Center at Nellis AFB in Nevada. The ITAS center located at Nellis AFB compiles the data from the RIIS and converts it into visual representations. These graphics are presented to aircrews and other sources for debrief.

Williams helped develop the Lancer MOA back in 2002.

This sectional map shows the location of the Lancer MOA. Pilots take great care when entering MOAs, because military jets train in these areas.

“When Reese AFB, located in Lubbock, closed in the early ’90s, there were three separate MOAs, the Reese Four and Five and the Roby MOA,” Williams said. “I worked with the Federal Aviation Administration to develop one MOA out of three. Since this airspace condensation gave approximately 3,000 square miles of airspace back for non-military use, the FAA was very cooperative in developing the new Lancer MOA.”

The Snyder ESS facility site manager is Bill Clingenpeel, an employee of AHNTECH Inc., the private contractor for operations. He explained that his facility provides precision tracking of the aircraft inbound for a simulated bombing run. His job is to provide electronic warfare in the form of a hostile threat environment that bomber crews might encounter while penetrating a foreign airspace.

“We’re the bad guys on the ground,” Clingenpeel said. “We send up signals that simulate tracking radar, antiaircraft artillery and surface-to-air-missiles. It’s the aircrew’s job to avoid us, get in there and do their damage.”

This radar dish is a smaller version of MUTES. These remote stations are located on ranches scattered throughout the Lancer MOA.

Clingenpeel said that the results of this intense training are worth the investment in money and time. It’s extremely rare to hear of a bomber being shot down.

“Our job is to bring ’em home,” said Clingenpeel.

The ESS building houses the machines that run the radar simulations. These include communication radios, transponders, radarscopes and computers used to make sense of all the data sent and received. The cool temperatures maintained in the rooms keep the electronics operating properly. Outside the building in the semi-desert environment is the radar hardware. The MUTES radar dishes will rotate to capture incoming aircraft and transmit simulated antiaircraft weapons and radar tracking signals. The TRAINS will receive data from the aircrews.

As Williams describes the various pieces of equipment, a loud warning horn cracks through the otherwise silent air. The large MUTES antenna swings toward the northeast sky.

This radar screen, located inside the ESS building, displays the echo returns from various military aircraft in W Texas and NM. Each blip is identified by transponder codes that give information about the plane’s type, altitude, ground speed and direction

“That must be the B-52 inbound,” said Williams, pointing to a tiny white contrail in the cloudless blue sky.

The large antenna would periodically adjust a few degrees to compensate for the distance traveled by the bomber located somewhere high in the sky.

“The B-1 bombers normally operate below 26,000 feet while the B-52s operate above 30,000 feet,” said Williams. “The base of the Lancer MOA is 6,500 feet, but we restrict our operations to 12,000 feet and above. This is for noise considerations and for general aviation traffic avoidance.”

The tour concluded after the ESS facility was bombed and destroyed (in simulation) by the B-52H Stratofortress.

Back at the Winston Field terminal building, airport manager Roger Sullenger and his associate, Bob Snedeker, greet arriving aircraft. There is no self-serve fuel farm here. Instead, a personal friendly smile greets each pilot. Snyder has become a popular stop off for pilots wanting to refuel after a long cross-country flight. Word travels fast about the friendly atmosphere, free courtesy car and reasonably priced fuel, which are all valuable commodities. Roger says that the ESS facility and those that run it are good neighbors.

“We’re always asked what the strange-looking building and radar dishes are about,” Sullenger says as he parks his fuel truck next to a newly arrived Mooney.

Ready to greet arriving aircraft at the Snyder Winston Field Airport are lineman Bob Snedeker (left) and airport manager Roger Sullenger. Personal service is their specialty.

Pilots fly in from all over the region. The Mooney driver was from Houston, on his way to catch the last of the snow skiing season in Red River, N.M. Another plane landed and parked in the tie-down area in front of the terminal building. The pilot of this Grumman Tiger was on his way to Colorado from La Grange, Texas, to visit family. Both pilots said they’ve made Snyder their preferred stop off because of the ease of access, friendly service and competitive fuel prices.

Local pilot and aviation enthusiast John Rogotzke was at the terminal building promoting his upcoming eighth annual Snyder Fly-In, scheduled for June 21. The Texas Air Museum and the local chamber of commerce sponsor the event, which features static displays of GA aircraft, warbirds and an antique car show. Vendors supply plenty of food and soft drinks. Fuel is sold at cost and the food is free for fly-in pilots.

Winston Field has become a great place to stop off for a visit. The city of Snyder and Scurry County enthusiastically support the airport and the ESS facility located on the airfield.

For more information about the Snyder Electronic Scoring Site, call Dwight Williams at 325-696-3666. Email John Rogotzke about the fly-in at John_Rogotzke@oxy.com. Visit or call Roger Sullenger at 325-573-1122 for information about Winston Field.