By Di Freeze

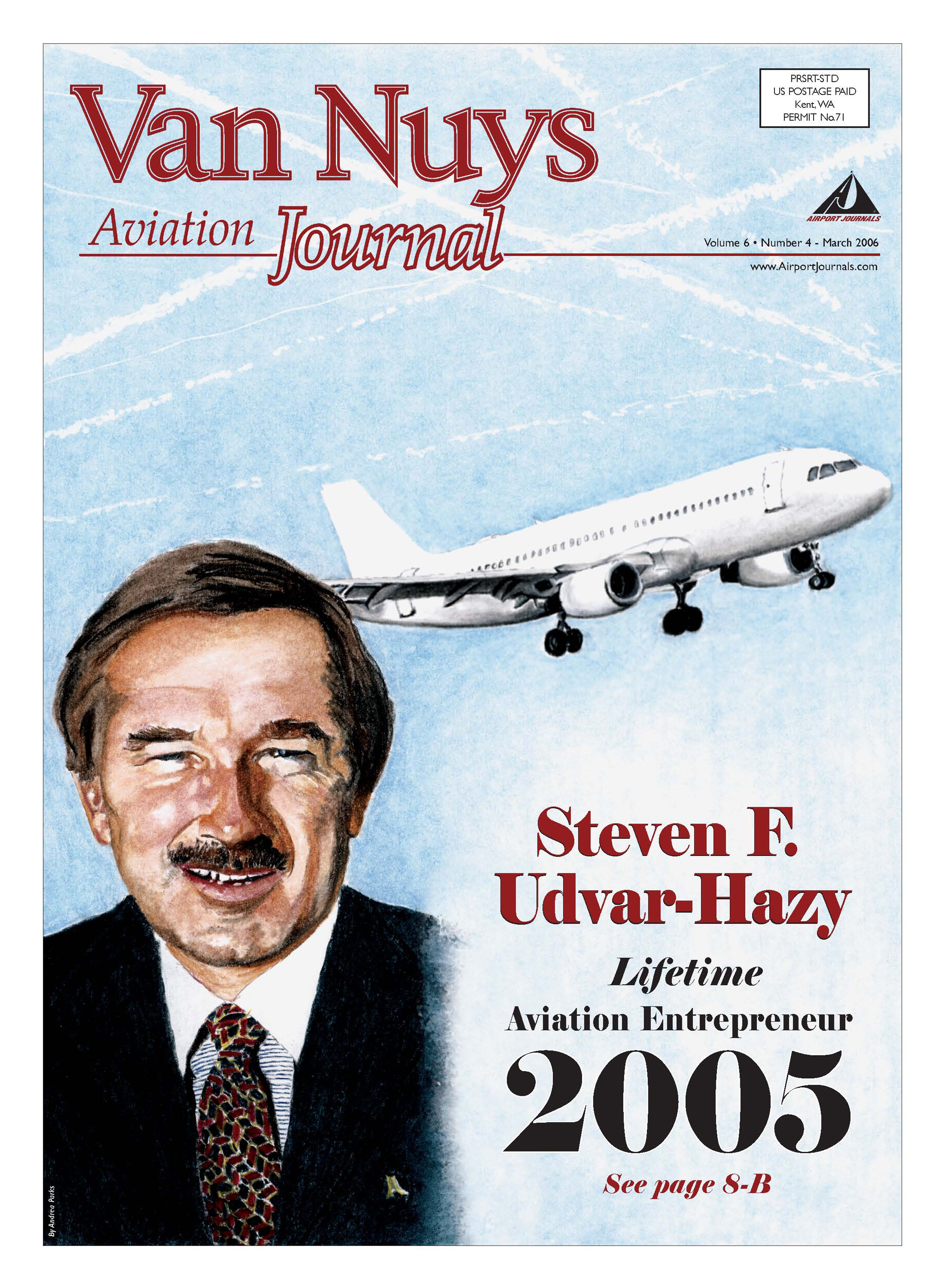

Steven Ferencz Udvar-Hazy, Airport Journals’ Lifetime Aviation Entrepreneur award recipient, is the epitome of an aviation entrepreneur. Born in 1946, in “Buda” on the “hilly side” of Budapest, Hungary, Steve Hazy became fascinated with aviation at the age of 7. That was when his father, Erno Udvar-Hazy, took the youngster to the Budapest Air Show, an eye-opening and life-changing experience.

“They had wonderful air shows every summer at the main airport at Budapest,” the 59-year-old aviator said. “It was a small grass airfield. There were Yaks, sail planes, MiG-15s. Just the sound and smell of airplanes was very captivating.”

Hazy, chairman and CEO of International Lease Finance Corp., a $40 billion global aircraft-leasing empire, and benefactor of the world’s largest aviation museum, recalls that one thing in particular enthralled him at his first air show.

“It was a beautiful, clear, sunny day,” he said. “I remember the chrome-like propeller of this Yak Russian aerobatic aircraft. As the pilot was starting the engine, the sunshine was reflecting off the three propellers. It was fascinating for a child.”

At that moment, the young boy decided he wanted to be a pilot.

“Living in a communist country, airplanes represented a sense of freedom,” Hazy explained.

In 1954, 8-year-old Steve Hazy took his first flight, on an LI-2, a Russian-built DC-3.

“It was in the summer, on a domestic airline flight from Budapest to the city of Miskolc and then back,” he said. “I really loved that.”

A flight he recently took on the same type of aircraft–but this time in the left seat–brought back fond memories.

“They restored one of these LI-2s in Hungary,” he said. “I got to fly it out of the same airport where the original air show was, just a few months ago.”

When Hazy was 11 or 12, he began studying flight schedules.

“I went to all the ticket offices of the foreign airlines in Budapest, and got all their flight schedules,” he said. “I would study what airlines flew where, and what equipment they flew. I just thought it would be fun to know where all the airlines were going and when and how.”

With a grin and eyes sparkling, he said it paid off later.

Good-bye, Budapest

From what he knows of family history, Hazy describes his ancestors, in the late 19th century, as “educated and somewhat aristocratic.” In the 1920s and early 1930s, Erno Udvar-Hazy, a surgeon and sports medicine specialist, invested in the textile industry. However, Steve Hazy said the family had virtually no material possessions when he was growing up.

“We lost everything,” Hazy said. “From my perspective as a child, we had nothing. My father’s car was taken away. All of our properties were nationalized, taken away by the Nazis or the Russians.”

In 1958, shortly after the Soviet Union violently put down the revolution, the senior Udvar-Hazy decided it was time he and his wife, Etel, removed their family from communist Hungary.

“It was pretty bad,” Steve Hazy said. “Under the Nazi regime, the Germans destroyed most of everything. The Russians destroyed what little was left. There wasn’t a lot of hope for a young person in the ’50s.”

The family fled to Sweden. When Steve Hazy was 13, they emigrated to the U.S. Etel shouldered the financial responsibility, since her husband suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and other ailments. The family survived on her $65-a-week salary from an entry-level job in the fashion industry. Although the first few months were difficult for the youth, who only spoke Hungarian, Hazy soon adapted to his new country and language.

“When you’re young, the languages come easy,” he said. “My parents put me in a Catholic parochial school in New York City. The nuns were good teachers. I picked up the language quickly.”

Immersed in aviation

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy, Airport Journals’ Lifetime Aviation Entrepreneur award recipient, became fascinated with aviation at the age of 7, when he visited the Budapest Air Show. “Living in a communist country, airplanes represented a sense of freedom,” Hazy

While living in New York, Hazy spent many afternoons at Idlewild Airport in Queens (presently John F. Kennedy International Airport). He made friends with mechanics, so he could watch them work in the hangars. Also, he made frequent trips to the control tower, where he’d take pictures and carefully track planes, entering where they were going carefully in his notebook.

In 1961, while visiting friends of his parents in Galion, Ohio, 15-year-old Hazy took his first flight on a U.S. general aviation aircraft, a Piper Cub.

“There was a small airport there,” Hazy said. “They had Piper Cubs and Tri-Pacers, and Cessna 195s. I talked several people into taking me up and got to feel the controls.”

In 1962, the family moved to Los Angeles. The move was a way for the family to be close to Andrew Hazy, Steven’s older brother, who was studying molecular physics (on scholarship) at UCLA. Also, it was hoped that the weather would be good for their father.

At the age of 16, Steve Hazy started taking lessons at Whiteman Airpark, near Burbank Airport, in a Cessna 150. To afford the $9 an hour needed to fly the 150, and the equal amount needed to pay the instructor, Hazy held a couple of part-time jobs.

“I would lifeguard in the summer, for two bucks an hour, and I washed cars for a dollar,” he said. “I didn’t have a lot of money, so I could only take a few lessons at a time.”

Finally, he was able to solo at the age of 18. He recalls the strange feeling of taking off on his first solo.

“There’s no instructor, and you say to yourself, ‘I can’t make any mistakes; I can’t screw up,'” he said. “It’s a strange feeling thinking you’re in control and that you have total command of the whole environment.”

After high school, when it came time to pursue further education, Hazy wasn’t able to afford to go to a private school. He began attending UCLA, where he majored in international economics and business. His intention was to one day start an airline.

“At that age, you think you know everything, and you know nothing,” he said. “In my naiveté, I wanted to start an airline, and fly airplanes.”

For a role model, he looked to PSA.

“They were fun and innovative, different than the rest,” Hazy said. “And they had cute flight attendants. At 18, that’s important.”

While in college, Hazy continued life-guarding. At 18, he also started a consulting company, which he named Airline Systems Research Consultants.

In 1961, while visiting friends of his parents in Galion, Ohio, 15-year-old Steve Hazy took his first flight on a U.S. general aviation aircraft, a Piper Cub.

“I thought if it had a fancy name, people would think it was sophisticated,” he said.

To keep his age a secret, he had a few tricks.

“I would never appear in person,” he said. “I would write letters and send telegrams, and send secret little things in the mail to the airlines, telling them little things they could do to improve their operation. Most of them, of course, were rejected. But there were a few that listened.”

He said he felt he could help these companies because he “saw obvious imperfections in what they were doing.”

“Some airlines had too many types of airplanes, and I could see that they could consolidate and do things more efficiently,” he said.

Aer Lingus, a small government-owned airline in Ireland, became his first account in 1966.

“They had way too many types of planes,” he said. “Their whole operation was a mishmash. I wrote to them, suggesting a much straighter, streamlined plan. They liked what I thought, and they gave me free tickets to come to Ireland. They paid me $4,000, which was a lot of money in those days. I could buy a $500 car and keep $3,500!”

As he expected, the airline soon saw an improvement.

“I gave them a strategic plan that they pretty much follow to this day,” Hazy said. “And they’re still my client. It’s ironic. More than half their planes are leased from my company.”

The first million-dollar aircraft deal

At 21, as a UCLA senior, Hazy brokered his first million-dollar aircraft deal.

“I used to hang around at the airport after school, and I met Al Paulson, who passed away a few years ago,” he said. “We became friends. He came across an old bush pilot at Reeve Aleutian Airways, an Alaskan airline, who was looking for an Electra, a four-engine prop jet, because their DC-6s were unreliable up in the Arctic. He said if I knew of any Electras, maybe I could do something.

“When I saw that Air New Zealand was putting out a tender to sell an Electra, I approached them and said, ‘I might have a customer, but you have to pay me a five percent commission.’ They said, ‘Fine.’ We got the president of Reeve Aleutian to come down to New Zealand with me. He loved the airplane and bought it.”

Hazy was thrilled to receive $50,000 for “a day and a half trip to New Zealand.”

“That was a lot of money for a college kid,” he said.

He then brokered commercial aircraft through Air Intercontinental, a company he still controls. In 1972, Hazy helped Alaska Airlines lease a Boeing 727 it couldn’t afford to Mexicana, for $74,000 a month. It was a savior for cash-strapped Alaska.

“I started to realize that there was a whole business here that nobody was doing,” he said.

ILFC

He soon realized, though, that there wasn’t a lot of money in consulting, no matter how intellectually rewarding. There was more money in brokering, but ultimately, he believed you had to own the planes and control them to really make money. That realization was the beginning of Interlease Group Inc., which would become International Lease Finance Corp. Hazy formed the company with two partners, Leslie and Louis Gonda.

“We had this crazy and irresponsible idea that we could lease planes to airlines,” Hazy said.

Leslie Gonda, a fellow Hungarian, had escaped after the war to Switzerland, and later to South America. The holocaust survivor had done well in Venezuelan real estate. Lou Gonda, his son, was two years younger than Hazy. Hazy met Leslie Gonda through his father.

“He was sending money to his Hungarian relatives back in the old country, and my dad was helping him facilitate that,” Hazy explained.

In September 1973, the Gondas and Hazy each invested $50,000 to form ILFC. Through the company, the trio would revolutionize the way typical leases worked, by introducing the world to a simple concept now known as the “operating lease.”

“Up until that time, airlines bought their planes with bank financing or long-term tax leverage leases, which usually lasted for the full life of a jet airplane,” Hazy explained. “Our idea was that the airline industry was changing so fast that airlines shouldn’t have to keep a plane for their full useful life. What if an airline just needed a plane for three years, or five years? Nobody was really offering a service where airlines could lease a plane for a finite period, and then do something else. That was the new concept that we introduced to the airline industry.”

Hazy realized that airlines sometimes had obsolete airplanes, since they were “tied” to a particular aircraft, even though it was no longer the most efficient aircraft to operate.

“We also felt that the financing challenges for the airline industry were just growing out of proportion, and the traditional sources of financing couldn’t provide this service,” he said.

Leslie Gonda, who will turn 87 this August, and remains active as an ILFC advisor and chairman of the board’s executive committee, was the “responsible, honorable, mature member of the group.”

“The two younger guys had long hair and wore gold chains and bell bottoms,” Hazy recalled with a broad smile. “We didn’t look like the Wall Street types, so we needed an elder statesman, when we were talking to banks and other government agencies, and so forth.”

Lou Gonda, who retired from day-to-day involvement at ILFC in 1995, but remains on the board, was “more involved in the contracts, legal, public relations areas and personnel.”

“I was the one who was more involved in the aircraft, aviation, airline relationships, and cultivating those relationships with the customers,” Hazy said. “So, I was out hustling, Lou was doing the legal and contractual work, and Mr. Gonda managed the bank relationships and investors. He had the mature image that we needed to show this was a respectable organization.”

The company’s first transaction was acquiring a Douglas DC-8, which they bought for $2.2 million from National Airlines.

“We leased it to Aeromexico, which at that time was still owned by the government of Mexico,” Hazy said.

The Gondas and Hazy had a simple plan. It was to “maybe grow to perhaps six or 10 planes, and then retire.”

“That plan didn’t quite work out,” Hazy said. “We hit the 10-plane level in about two years, and then we said, ‘Why don’t we grow some more?’ And then we wanted to grow some more.”

At that time, the airline industry was going through a modernization period.

“They were reequipping, from propeller planes to jets,” Hazy recalled. “We saw tremendous demand, including international demand. So we kept buying, selling and leasing planes. In April 1977, we bought our first new plane, a Boeing 737-200. That started a whole new chapter in the company’s history, transitioning from used planes to new planes.”

Hazy said that in the early years, they kept “doing more transactions, borrowing more money, and getting further into debt.”

“We were trying to conserve capital, so the three founders, we each received a salary of $600 a month,” he said. “We were putting a lot more money into the company than we were taking out.”

In order to be able to lease more planes, the founders, constantly short of funds, put together limited partnerships.

“Leslie would bring in investors to put in a few hundred thousand dollars,” Hazy explained. “We would put a few hundred thousand dollars into the deal; we’d borrow with bank financing. We just kept layering and building a portfolio. And we were also doing some buying and selling, so we could make a little profit, and invest that money into buying more airplanes. It was a very humble beginning.”

Hazy and the Gondas had a very small “staff” in their Beverly Hills office.

“We had one secretary, and one young lady who did everything; she was the office manager, typist, banker and accountant,” he recalled. “I think our first office was about 900 square feet.”

Going public and merger with AIG

In 1973, Steve Hazy and two partners each invested $50,000 to form International Lease Finance Corp. Through the company, the trio revolutionized the way leases worked, by introducing the world to a simple concept now known as the “operating lease.”

By 1983, ILFC continued to lease planes to existing airlines intent on seizing market opportunities opened by deregulation. They were also leasing planes to start-up carriers that had sprung into existence. That year, after being a private company for nine years, in March 1983, Hazy and the Gondas took ILFC public, with a $26 million IPO.

The founders kept about 80 percent of the company, and sold 20 percent to the public for $26 million. They sold 1.6 million shares, with the stock at $16.25 a share.

“At that time, we were about a 200 million dollar company,” Hazy said. “Now we’re about a 40 billion dollar company. We’re 200 times bigger. … I think we managed the size very well. … You go through growth spurts and then a little bit of a plateau.”

He said one of the reasons they went public was that ILFC wanted to access public debt financing, issue bonds and sell more stock, to become less dependent on banks. Also, buying planes and financing them individually was a very “tedious process.”

“And we wanted to finance the whole company rather than individual pieces of aircraft,” he said. “We found that if we got a bank loan, and we leased an airplane to, say, a British airline, and then we wanted to move it three years later, to maybe an Italian airline, the bank’s lawyers went ballistic. They were very insecure about the idea of registering a plane in one country, and moving it somewhere else. I was very much in favor of weaning ourselves away from these banks, and financing the company, rather than individual assets of the company. That gave us a lot of flexibility and freedom to do whatever we wanted to do. That transition really helped our company.”

By 1990, the partners had become concerned that their capital needs were exceeding their capabilities. That concern led to a very profitable merger with American International Group, the world’s leading international insurance and financial services organization.

“We’d already grown the company quite a bit,” Hazy said. “Also, Mr. Gonda was already 71 years old at that time. We felt that having worked at this for nearly 17 years, it was time to maybe cash in some of our chips and associate ourselves with a large, public, international company that would still give us the autonomy to run our company, but yet have some degree of financial security. We basically did a merger where we swapped our shares for their shares.”

The transaction between AIG and ILFC, essentially a tax-free stock swap, was worth about $1.3 billion at that time.

“If you had bought $1,000 worth of the company stock in 1983, by the time we merged with AIG, it was worth nine times that amount,” Hazy said. “It went up nine-fold in seven years. Wall Street loved us. Because the company kept growing, earnings were going up, we kept increasing our dividends, the share price went up. We split the stock, so we had a lot of loyal followers.”

Hazy has seen a little difference in how the company is run since that transaction.

“Being bigger just means you spend more of your time managing people and dealing with people issues, rather than transaction issues,” he said.

A culture of fun

Steve Hazy said his favorite part of being CEO and chairman of ILFC is “turning the lights on for younger management guys, as to achieving what they think is impossible to achieve and overcoming challenges.”

Hazy says the entire culture of ILFC is “very fun.”

“What we’re doing is a joy,” he said. “We set very high goals and we have very high standards. But we’re very informal, very creative, and nurturing to our team. That’s our philosophy.”

Hazy doesn’t have to think long to decide what the favorite part of his job is.

“I think it’s to turn the lights on for a lot of our younger management guys, as to achieving what they think is impossible to achieve, overcoming challenges, getting transactions done in foreign countries that they think are virtually impossible to achieve,” he said. “That’s very rewarding to me personally. It’s not the money; it’s more just the challenge.”

Obviously, “fun” figures a lot into Hazy’s environment. In fact, he says he runs ILFC simply “for the fun of it.” He says ILFC “is an extension of a hobby, and a passion, rather than a business” and that his present responsibility is “to be the architect of the transactions” ILFC creates.

“I strategize about what kind of airplanes we should own, what airlines are worth doing business with,” he said.

He also cultivates relationships with CEOs of airlines throughout the world and deals with heads of government.

“A lot of foreign airlines are still government owned, so there’s a lot of interaction with presidents of countries, prime ministers and ministers of finance who are very interested in their airline’s affairs,” Hazy said.

His responsibilities also include “teaching, coaching, motivating and coming up with new ideas.”

“How to do it better, how to stay steps ahead of our competitors, how to keep Wall Street happy, keep the SEC content, all these things,” he said. “It’s many, many heavy-duty responsibilities. But leadership is the most important. Somebody has to send out the right signals.”

For the future, Hazy said ILFC is looking at regional jets, as well as infrastructure.

“Things like airports, particularly in a lot of third-world countries,” he said. “We’re looking at a lot of different possibilities. But right now, since we have a relatively tight organization, most of our management has very little free time to wander off course. We’re staying with our proven formulas of success, but from time to time, we look at diversifying our activities. I think we know our strengths, and we also know our weaknesses. We want to be the best at what we do, in our line of business, rather than be number two or number three in some other segment.”

ILFC’s relationship with AIG remains strong, despite the recent massive management shakeup within the company.

“We have a great relationship,” he said. “We saw eye-to-eye with Mr. (Maurice) Greenberg, the previous CEO for almost 40 years, on the direction of our company. He was also a great believer in delegating all the responsibilities to us. We’re not interfered with. We have a lot of autonomy, as long as we perform, and they’re proud of the results.

“AIG has been very hands-off. This crisis has not affected us as much directly, but 2005 was an extremely difficult period for us. A lot of the AIG people that we dealt with for 15 years left the company. There was tremendous regulatory scrutiny of AIG and our company. We were X-rayed from every direction, to see if there were any irregularities. That was frustrating and took a lot of time. But I think we’re over that now.”

Steve Hazy donated more than $60 million to the Smithsonian to establish a companion location for the National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall. The new facility near Washington Dulles Intl Airport bears the generous benefactor’s name.

Hazy said ILFC, which now employs about 150, has a positive and constructive relationship with Martin Sullivan, AIG’s new CEO.

“We have a strong mutual trust with the new board,” he said. “Our company is still guided by the same principles of integrity as they were before. I think the worst is over, though. Hopefully, we’re getting back to some level of stability.”

ILFC presently has more than 800 aircraft in their fleet, making that fleet larger than any existing airline. All of the models are modern, stage-three aircraft.

“There’s about 300 wide-bodies, and a little over 500 single-aisles–737s, 757s, A320 family,” he said. “Right now, we have more Airbuses on order than Boeing. The fleet is close to 50-50. We take delivery of about 100 new planes a year, Boeing and Airbus. For the last three years, we’ve taken over $5 billion of new planes a year, for Boeing and Airbus. This year, I think it’s going to be about five and a half.”

The company also manages another 130 aircraft. ILFC, one of the two largest aircraft lessors in the world, is a customer of their only real viable competitor, GE Commercial Aviation Service.

“They’re more domestic oriented,” Hazy said. “And they’re more of a finance company, while we’re more of an aircraft marketing company. There’s a huge structural difference. We’re GE’s largest commercial customer in the world. The Pentagon is their number one customer. So it’s kind of an odd love triangle, GE and ILFC.”

As for the future, Hazy said ILFC has no plans to become involved in general aviation.

“My father taught me a lesson when I was very young. He said, ‘You don’t have a big head and a small head,'” he recalled. “You do things in a big way, which doesn’t leave you time to do the little things. In other words, it’s just as much work to do a small plane as a big plane, maybe more, because you have to baby-sit the customer more. We’re not equipped to do mass volume of aircraft.”

Looking back

Steve Hazy has flown various aircraft over the years and has about 9,000 flight hours (8,500 in jets). These days, he’s comfortable in the left seat of a Gulfstream V.

Hazy recalled that in the early days of ILFC, people were skeptical about what they were doing. That skepticism made the founders all the more determined to succeed. Hazy considered watching the transformation from doubt to belief one of the most fun parts of those early years.

“When you start a company that has a novel business model, you’re going to run into a lot of ‘experts’ who will say, ‘This will never succeed,'” Hazy said. “A lot of banks, a lot of people who are considered sophisticated, will tell you all the things that are wrong with what you’re trying to accomplish. The more we heard people say, ‘This is never going to work,’ the more we were determined that we did have the successful formula, that we did have something that the worldwide airline industry needed. The people who were the skeptics, three, four years later, would go around saying, ‘Oh, we were their best friends,’ and ‘We are your number-one supporters.’ All of a sudden, their tune changed. So that was kind of fun to watch.”

But Hazy said the intention was never to “prove anything” to those skeptics.

“We just believed that what we were doing was the right thing,” he said. “We didn’t hold any animosity towards the skeptics. But it was kind of fun to see them, all of a sudden, change the color of their outfits. They became big supporters, claiming they were always behind us, backing us, when in the early days, in fact, many questioned our future success.”

Hazy the pilot

When Hazy and the Gondas founded ILFC, Hazy was working on his instrument rating. He got the rating shortly thereafter. In the mid-seventies, he got his commercial rating. In the company’s initial years, he owned various private aircraft.

“I bought a Cessna 150, and had a Piper Arrow,” he said. “I had my multi-engine rating. I was flying a Piper Seneca II. In 1977, that was our third year at ILFC, we ordered the Cessna Citation ISP, brand new. In those days, American Airlines had a contract to train Citation pilots at DFW, at the American Airlines pilot training facility. They had a contract with Cessna. If somebody bought a Citation, they went to American Airlines’ flight school. I got my type rating on the Citation in January 1978. So I became jet qualified and later we acquired a Learjet 25, and a Learjet 35A.”

A Gulfstream IV came next, in 1990, followed by a Gulfstream V in late 1999.

“I’m type rated in all these planes,” Hazy confirmed, “and I enjoy flying all of them.”

Hazy has flown all the Boeing planes that are currently in production as well as all the Airbus products.

“This summer, I’m going to fly the A380, even before it’s certified,” he said. “I’m looking forward to that. I plan to fly that airplane out of the left seat. I try to be as familiar as possible with all the planes that ILFC owns.”

Hazy, who has about 9,000 flight hours, of which 8,500 is jet time, normally flies himself on his business trips, since he loves to fly, and uses the opportunity to keep current.

“On overseas trips, we usually take two other pilots, because I need to work and rest a little bit,” he said. “But I also have some good flight time.”

Like father, like sons and daughter

Steve Hazy met his future wife, Christine, while buying an aircraft to lease to an airline.

“I met her at the airport in Salt Lake (Salt Lake City International),” he said. “She worked for Intermountain Piper. I was buying a Piper Chieftain to lease to SkyWest.”

While casually sitting on the desk in the office in July 1974, Hazy made Christine an offer he hoped she wouldn’t refuse.

“I asked her to come work for us,” he said. “I told her, ‘I’ll pay you double whatever you’re making.’ She seemed very capable, and she was good looking. She said, ‘You’re just some playboy here from Hollywood. Get lost.’ She threw me out of her office. So I sent her a round-trip ticket on Western Airlines, to fly down to LA, and said, ‘Check us out.’ She took up the offer and found that we were legitimate. It started out as just a friendship.”

Hazy and Christine married in 1980. She felt right at home in the aviation atmosphere.

“Her father was a Marine aviator, in WWII, and her mother was a Link instructor, of the WAVES (Women Appointed for Voluntary Emergency Service), the naval aviation branch for women,” he said.

Hazy has done a great job of handing down his passion for aviation to a new generation. That includes his children, of which three out of four are pilots. Still, he says he didn’t really encourage them to fly, unless they had their own motivation to do so.

“They’ve just been around airplanes and aviation all their lives,” he said. “They like it. My oldest son, Steven, has already graduated from Stanford University. I think he was probably the youngest person in the U.S. to get his Boeing 737 type rating. He became a captain of a 737 at the age of 22! Of all our children, he’s probably the most enthusiastic about flying. He loves to fly.”

Karissa Hazy is enrolled at Stanford and is in an overseas studies program in Australia right now. She soloed at Embry-Riddle University.

“Our younger son, Trenton, is a Stanford freshman and has already taken lessons on a Skyhawk,” he said.

Courtney, 13, hasn’t displayed an interest yet in being a pilot.

“She just wants to sit in the back of the GV,” Hazy said. “She likes horses and animals.”

That interest was handed down from Hazy’s mother, now 96, who raised race horses on their farm in Budapest.

“My mother loved animals,” Hazy said. “She would go to the racetrack with her brothers before the war.” Etel Hazy, the youngest of 10 children, is the only sibling alive today.

Hazy also enjoys riding; his preference is Arabians. And he has a fondness for boats, which was one of his father’s passions.

“He raced boats on the Danube River,” he said.

Hazy doesn’t own any boats, however.

“We charter whenever we want to go,” he said.

To make sure his children don’t forget their roots, Hazy has taken them to “some of the worst places in the world.” That includes impoverished parts of Africa and Asia.

Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center

The Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Washington Dulles International Airport is the companion facility to the Museum on the National Mall. The building opened in December 2003, and provides enough space for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum to display the thousands of aviation and space artifacts that can’t be exhibited on the National Mall. The two sites together showcase the largest collection of aviation and space artifacts in the world.

Hazy explained his motivation for initially giving the Smithsonian $60 million, which was the institution’s largest donation to date.

“They approached me, I think, because they were running out of ideas,” he frankly said. “They had this huge piece of land that the federal government specifically allocated at Dulles International Airport for this museum. The fundraising hadn’t gone well; they had some token investments. I think they came to me for two reasons. One was that they knew we had a good relationship with companies like Boeing, General Electric, Lockheed, Honeywell, all the people in the aviation business. I think they were expecting us to make a small donation, and then hopefully encourage some of the aerospace companies, like Airbus, United Technologies and GE, to come in with some support.”

The timing, as well as a sense of “reimbursement,” was another reason he thought the donation was crucial.

“We were coming up on the 100th anniversary of the Wright brothers’ first flight,” he said. “If we were going to get this project going, get it done on the 100th anniversary, we needed to push the buttons. I felt in my heart it was the right thing to do, for our country that gave me so much, and also to have one place on this planet where all of aviation history and aerospace history could be under one roof.”

Hazy had strong ideas about what a museum should be and represent.

“I’d been to a lot of airplane museums, from Duxford, to the Smithsonian on the Mall, the main Air and Space Museum, and I always felt that a museum is more than just a display case,” he said. “It’s really an educational fountain of ideas and inspiration. I remember when I was a young child, and I would go to a museum, my eyes were big, because everything seems bigger, and more impressive than when you see it as an adult. I felt that the current facility, the original Air and Space, which was the most visited museum in the world, was really a deprived facility, because it couldn’t display most of the things that people want to see. They could only display a very small fraction of what’s out there.

“We needed to build a big facility to accommodate the Concorde, the Enola Gay, all the WWI and WWII stuff and the space shuttle. The downtown facility just couldn’t do that. We needed what they call the ‘Nation’s Hangar.’ This was the only way to get it done. And it worked.

When Hazy learned exactly where they were in the process, he realized that a small donation wouldn’t help.

“I realized that $1 million here, $1 million there, wasn’t going to get them across the finish line,” he said. “Plus the cost of construction keeps going up, so the longer this thing dragged out, the further away the goal would be, and the more unachievable. They really needed to get a boost. I thought, ‘If I make a meaningful contribution, that will motivate a lot of the other supporters of aviation, the big players in aviation, to come in. Instead of a $1 million contribution, they’d make a $5 million contribution. That’s exactly what happened.”

Hazy said the decision to make that large donation was swift.

“When I heard about the whole story, it took me about five minutes to make a decision,” he said. “I never even called my wife. Normally, I consult her on commitments of that size.”

He was right. Once he made his commitment, others followed his example.

“It was a lot easier to get Airbus and Rolls Royce and all these aerospace companies to come in, in a more generous way,” he said. “It would have been almost embarrassing for them not to come in. It really got us to the finish line. We raised about a quarter of a billion dollars. That’s not an easy task, to go around begging people to make a donation.”

Hazy was personally very involved in the campaign.

“Once I made my commitment, Congress and the Smithsonian Board, Larry Small, secretary of the Smithsonian, felt they had enough to get going,” he said. “Construction was contracted for it; all the architecture was done. We made a few changes, and then once construction got under way, it was very easy to raise money, because people could see the brick and mortar, and they could see that it was actually coming alive. Whereas before, when it was just on paper, people said, ‘Is this ever going to happen?’ Once the thing was underway, it was a lot easier for people to make contributions.”

Hazy didn’t stop at $60 million.

“I went up another $5 million, because they needed more money,” he said. “Now they’re adding another wing. It’s going to be a restoration center. I’ve donated another million, as a matching fund to help some other people come in.”

Hazy and his family have made other donations. They gave $3.5 million to Dixie State College, in St. George, Utah, where the business college is named in honor of his parents, and have generously donated to UCLA. They’re also big supporters of Stanford University, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the California Science Center.

“They just opened a new aviation aerospace museum that was sponsored by our family foundation,” he said. “We try to be committed to good causes.”