A few years ago , I was a leader of 14 high school boy scouts on a six-day backpack trip in the Wyoming Bridger Wilderness (Wind River Range). Our hike was to culminate in climbing Gannett Peak, at 13,800 feet, the highest in Wyoming. Our route to Gannett Peak was on National Forest Trail #801, going south for 25 miles starting near Dubois, Wyo. This trail is classed as one of the five most scenic mountain trails in the U.S. (south 48). When we finally reached the base of Gannett Peak, only two boys, Scott Tandberg and Chris Near, felt comfortable and eager to climb the mountain.

This is in glacier country, so our mountain was snow-covered from its base to its summit. The two boys and I left for the climb early the next morning. Some of the route was so steep that even with the snow being soft, we had to grasp the handle of our ice axes, moving only one support at a time (i.e., only one foot or the ice axe). Coming off the peak, we had to cross two tricky snow bridges. On the second one (with the boys ahead of me as usual and down below me), I called down to the boys, prior to crossing the snow bridge. They said there was a big crack just below where I was standing. So I quickly, but very carefully, crossed the bridge. What a relief reaching the other side! Over the years, I had summited many of Colorado’s 14,000-ft. peaks with scouts, but this was a very special and rewarding climb.

During one of our evening campfires on this trip, someone mentioned a WWII bomber that had crashed. None of us knew anything about such a crash, only that one had gone down not far from where we had been hiking. The subject piqued my interest, so I vowed to research the story. Years went by, and now, as the owner of these exciting “Airport Journals” aviation newspapers, I decided to finally look into the story of this crashed bomber. After calling several forest ranger districts and the Wyoming Historical Society, I started to get conflicting stories. To my surprise, there were actually two bombers that crashed in Wyoming during WWII. One of the crashes was found at the time the plane went down, but the other one (a B17 with a deceased crew of 10) wasn’t found for two years.

Aug. 14, 1943—a B24 four-engine bomber with a crew of 11 crashed in the Shoshone National Forest near our beautiful Trail #801.

The map of this area is the largest map on the right, showing Gannett Peak, the glaciers and the crash site. The plane was almost immediately found as ranchers saw a “fire ball” in the sky.

“Someone called in to report a forest fire on the other side of Trail Lake,” Pat Boland said on Aug. 14, 1943. According to accounts in the newspapers, the four-engine bomber crashed into a mountain peak located on the upper South Fork of Torrey Creek between Hidden Lake and Lewis Lake. According to the story, “The bodies of the men were badly mangled and burned when the bomber exploded as it hit, starting a forest fire in that location.”

The fact that the bomber had crashed wasn’t known until firefighters, under the direction of Forest Ranger C.S. Thornock, arrived at the scene to extinguish the blaze. An official investigation party from the Pocatello air base arrived in Dubois shortly, including staff officers, doctors, and 50 enlisted men with trucks and ambulances. Horses were secured from the Trail Lake and CM Ranches to pack into the site. The group from Pocatello later came and stayed at the ranch to investigate the accident. According to the officials from the air base, the plane was way off course.

Forty six years later, in the fall of 1989, Jane and Scott Maller of Sundance were bighorn sheep hunting in the area when Maller found a dog tag which had belonged to one of the crew of the crashed bomber. The crash site has been named “Bomber Basin” by forest rangers in recent years; however, the area is known by the old timers as Henton Valley.

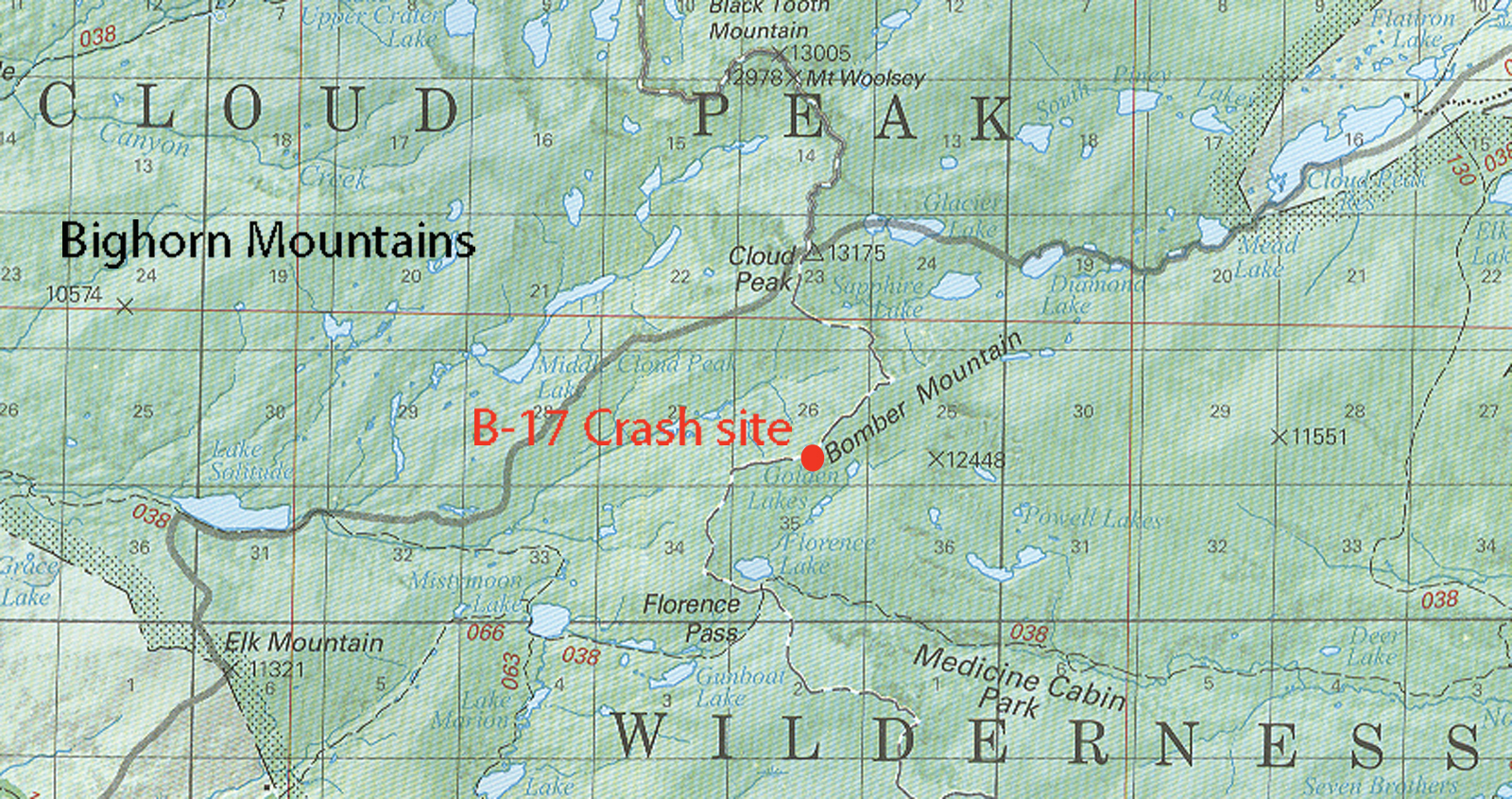

On June 28, 1943, there was a B-17F four-engine bomber with 10 aboard that crashed in the Big Horn Mountains in North Central Wyoming. This crash was not found for several years!

On June 28, 1943, there was a B-17F four-engine bomber with 10 aboard that crashed in the Big Horn Mountains in North Central Wyoming. This crash was not found for several years!

As America entered WWII, young men from all across the U.S. were drafted to serve their country. While some were as young as 17 and had no real-world experience under their belts, others had led full lives complete with careers and families. Once drafted, these men put their personal lives on hold, but some would never be given the opportunity to return to the prewar life they had known. One such fated flight crew never left America’s shores, and the circumstances of their deaths have remained an intriguing mystery with questions that will likely remain unanswered.

After completing their various forms of training, 10 men reported for flight duty to the 318th Bomber Squadron at the Army Air Base in Walla Walla, Wash. Under the command of pilot 2nd Lt. William R. Ronaghan, the crew was reassigned to the Plummer Provisional Group at Pendleton Army Air Base in Oregon. The Plummer Group was required to have 30 B-17F Bombers in its unit. Since one of the original crews was unable to accompany the group, Ronaghan’s Bomber was ordered to fill the 30th spot on June 27, 1943. In addition to being a replacement, Ronaghan’s plane was also missing one of its original 10 members. In this man’s absence, assistant radio operator Charles E. Newbum, Jr. became the crew’s unlucky 10th member.

Upon arriving at Pendleton at 4:00 p.m. on June 28th, 1943, Ronaghan and the rest of the crew were to fly to the Plummer Group’s home base in Grand Island, Neb., later that evening. After filling up with fuel and picking up the remaining cargo in Grand Island, the Plummer Group would leave to participate in the bombing campaign against Nazi Germany.

At 8:52 p.m. on June 28, Ronaghan’s B-17F Flying Fortress was cleared for takeoff along with one other remaining B-17F from the Plummer Group. Around midnight, pilot Ronaghan radioed the plane’s position near Powder River, Wyo., 40 miles from the then operating Casper Army Air Base. Following this report, nothing further was heard from the 10 men. On June 29, Pendleton was notified that the plane was missing, and on July 18 and July 21, notices were sent to the crew’s next of kin that the plane was missing. No further details were released, leaving family members to speculate that neither the plane nor crew had yet been recovered.

Since the plane was still missing in August 1944, the Army suggested a search of Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains, Absaroka Mountains and the Bighorn Mountains. Despite help from the Utah Mountain and Ski Corp, no wreckage was found. When the Army contacted forestry officials for each of the three ranges, the Bighorn Mountain Forest supervisor suggested that the only area untouched during the previous year was a five-mile radius around the Bighorn’s tallest peak, Cloud Peak. Mysteriously, the wreckage was still not spotted.

Then, on Sunday, Aug. 12, 1945, Wyoming cowboys Berl Bader and Albert Kirkpatrick noticed something shiny on the skyline. Climbing up the unnamed mountain ridge to investigate, the two discovered the wreckage and the deceased crew. Reporting the wreckage to the nearest Forest Service work site, men from Rapid City, South Dakota’s Army Air Base and personnel from Colorado’s 2nd Air Force headquarters joined in the recovery effort on Aug. 13. Civilians who were enjoying Wyoming’s mountains and encountered the recovery team were asked to help in transporting the bodies down the mountain. On Aug. 17, 1945, the crewmembers were taken to Rapid City to be returned to their families, and on Aug. 18, the Army began contacting families with word that the plane and their loved ones had finally been found.

Although the plane reported its last position 40 miles northwest of Casper, the wreckage was found 110 miles north of Casper, indicating that the plane was either off-course or its navigational instruments were malfunctioning. It appeared the plane needed just 50 to 100 feet more to have cleared the mountain ridge. No matter what caused the plane to crash, it is surmised that the plane simply was not found earlier as its paint allowed the wreckage to blend in with the mountain’s giant rocks. Not until the paint began to wear off and the shiny aluminum reflected in the sunlight was the plane spotted.

Some rescuers feel that at least one of the crew may have miraculously survived the crash. During the recovery operation, one well-clothed man was found propped next to a rock. Beside him were an open Bible and his billfold with family members’ pictures lying next to him. Among the wreckage were letters to and from sweethearts and wives of the crewmembers, an artist’s kit of paints, well-preserved clothing and flight jackets, and several other personal effects of the crew. Several items are surely buried underneath the massive boulders. Today, much of the wreckage remains, although more and more curious spectators are carrying off pieces of the plane as mementos instead of preserving the site. Dispersed across a wide radius are the plane’s engines, landing gear, pieces of the fuselage, the plane’s tail section, the horizontal stabilizer, a radio, pieces of a gun turret and several other massive pieces of twisted aluminum that smashed into the mountainside.

In honor of the fallen men, the Forest Service christened the 12,887-ft. mountain “Bomber Mountain” on Aug. 22, 1946. The Sheridan War Dads and Auxiliary also placed a plaque recognizing the fallen men 1.5 miles southwest of the crash site on the shores of Florence Lake in late August 1945.

The memorial reads: “The following officers and enlisted men of the United States Army Air Force gave their lives while on active duty in flight on or about June 28, 1943. Their bomber crashed on the crest of the mountain above this place. Lieutenants: Leonard H. Phillips, Charles H. Suppes, William R. Ronaghan, Anthony J. Tilotta; Sergeants: James A. Hinds, Lewis M. Shepard, Charles E. Newburn, Jr., Lee V. Miller, Ferguson T. Bell, Jr., Jake E. Penick.” Their sacrifice to their country will always be remembered.

Richard G. Hansen is owner and publisher of Airport Journals and is an avid boy scout leader and outdoorsman with over 60 years of service to the Boy Scouts of America.