|

By Di Freeze and Deb Smith

Tex Hill lived a legendary life. One recent “legend,” passed from friend to friend via email, recounts a recent party held at the home of the 92-year-old and his wife Mazie. Hill invited 50 of his dearest friends to that get-together in Terrell Hills, Texas. According to his grandson, Lt. Col. Reagan Schaupp, who helped the popular ace pen “Tex Hill: Flying Tiger,” the bedridden hero’s partying didn’t stop with playing the harmonica. His doctor had told Hill his heart condition couldn’t take alcohol, but this was most likely Hill’s last hurrah. When his daughter, Shannon Schaupp, agreed to make him a drink, she asked if she should “lighten it up a little.” “No, I want the richest kind,” was his response. That perfectly describes the life of Hill, who died on Oct. 11, 2007, from congestive heart failure. From Korea to Texas Before he acquired his lifelong moniker, the man who grew to be one of America’s greatest wartime aviators—logging more than 3,500 hours of flight time and flying 150 combat missions—was born on July 13, 1915, under a less colorful name. David Lee Hill was born in Kwangju, Korea, where his parents, Dr. Pierre Bernard and Ella Hill, were missionaries. After developing health problems, his parents returned to America for treatment. The Hills and their four children boarded a steamer in 1916. After crossing the country to Virginia, the family acquired a 600-acre farm near Chula, Va. Dr. Hill hoped to return to the Far East within a few years. In the meantime, he would end up temporarily in Roanoke, Va., as pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church, whose fulltime pastor was volunteering for the war effort. After World War I ended, the family relocated to Louisville, Ky., where Dr. Hill would pastor the First Presbyterian Church. They moved on to Texas in 1921, when Dr. Hill accepted pastoral duties at the First Presbyterian Church of San Antonio. One of the perks of his job was the summer use of a home in Hunt, Texas, near Kerrville, offered by a church member. |

In the hill country, David Hill eagerly hunted, fished, swam and explored. He also picked up an interest from Hung Nim, the family’s Korean assistant, who was a skilled kite maker. Hill’s fascination led him to experiment with other instruments of flight, including building a model airplane out of a stick, some aluminum and rubber.

When Army Air Corps cadets began stopping by to visit Hill’s older sister Martha, he studied their uniforms and listened intently to their stories. One Sunday, after arriving at church, he coaxed a classmate into sneaking off to Winburn Field, a small grass airstrip on the other side of San Antonio.

Triple ace Brig. Gen. David Lee “Tex” Hill served as leader of the American Volunteer Group’s 2nd Squadron and commanded the Army Air Corps’ 75th Fighter Squadron and the 23rd Fighter Group. He was also the Texas Air National Guard’s first commander.

The two boys found a ride to the field, where barnstormer Dick Hair took them for a spin in his Travel Air E-4000 biplane. After they had returned to the field, the boys walked around the plane, while Hair described its aerobatic capabilities. It was soon time for him to take off and for the boys to get back to church. They would never forget that day.

Teenage adventures

After excelling in reading, writing and mathematics at Travis Elementary, Hill went on to graduate from the San Antonio Academy in 1928. That fall, he enrolled in the McCallie School, a prestigious military institution in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains around Chattanooga, Tenn.

By that time, his father had been serving as chaplain for the Texas Rangers, a group of rugged Texas lawmen, for three years. By the end of his freshman year, Hill’s slow Texas drawl earned him the nickname of “Tex.” His pranks and dares earned him something he liked less—several instances of school ground restrictions.

Tired of being “campused,” Hill and a fellow cadet ran away one winter day, hopping aboard a tender at the Chattanooga railway station. They quickly made friends with some hobos. The boys stopped briefly in Meridian, Miss., before boarding a boxcar headed toward Hulbert, Ark.

Tired and hungry, the boys soon called Dr. Hill, who wired money for return train tickets. School officials wouldn’t be as understanding; the two were campused for the rest of the year.

After a year spent at Main Avenue and Jefferson high schools, Hill returned to McCallie, where he lettered in football, ran track and took up boxing. He quickly became the best boxer at the school, winning the Tennessee Middleweight Championship in 1934, a few months before his graduation. He considered boxing as a career, until a match with an Army soldier revealed his limits.

“I survived that”

Hill graduated in the spring of 1934, near the top of his class and with hopes of enlisting in the Navy. Nearly 17, he was old enough to enlist, but recruits of his age had to supply letters of recommendation from community and civic leaders, as well as written parental permission. His parents were supportive of a military career, but Dr. Hill strongly urged him to consider going to college first.

Hill enrolled in the Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College, a military school in College Station, choosing chemical engineering as his major. In Texas A&M’s Corps of Cadets, he was assigned to Cavalry Troop A. After making friends with many of his fellow cadets, he was disappointed to learn that he was transferring to a new division for his second year.

After graduating from McCallie School, a prestigious military institution, Tex Hill attended the Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College, before finishing his education at Austin College, where this portrait was taken.

Hill changed majors, hoping to stay with his friends, but his attempt served only to affect his grades. When he returned home for the holidays, unmotivated and ready to drop out, his father convinced him to attend Austin College.

In the spring of 1938, Hill applied for the Army Air Corps’ aviation program, but failed to qualify. He next expressed his wish to fly pursuit planes to a Navy recruiter, and was glad he had listened to his father’s advice.

“In those days, you had to have a college degree to qualify for naval aviation training,” he said.

Hill was thrilled to learn of his acceptance as a candidate.

“I graduated in 1938,” he recalled. “Then I went straight in the Navy.”

He enlisted as a seaman, second class, and headed to Opa-locka, Fla., for Navy flight elimination training. Hill and 12 other candidates took a three-week class, which began with classroom training and concluded with 10 hours of flying instruction in a Stearman NS-1 biplane trainer.

“I survived that,” Hill laughed. “So I was sent to Pensacola as a cadet.”

Hill and the nine others who survived elimination training spent the next 13 months learning to fly all the Navy’s primary aircraft types, including the N3N Canary, Stearman NS-1, Vought SBU and O3U Corsair. Since Hill had an aircraft carrier assignment, he skipped the Consolidated PBY Catalina, going on to the North American NJ-1 and the Boeing F4B-4.

Nearly seven decades later, Hill revealed how much he enjoyed flying the F4B-4.

“We did our gunnery in that biplane,” he said. “I felt more comfortable in that airplane than in any airplane I’ve ever been in.”

Hill recalled that he “survived” that period, too.

“I graduated from Pensacola in ’39, in Class 121-C,” he said.

On the way to war

Hill graduated two months after Britain and France declared war on Germany, in response to its invasion of Poland. Newly promoted Ensign Hill was assigned to the West Coast to fly torpedo bombers.

“Admiral Nimitz signed my ticket as a naval aviator, and I went straight from Pensacola to the fleet,” he said. “I was assigned to Torpedo Squadron Three (VT-3) on the USS Saratoga (CV-3).”

In July 1941, Tex Hill and 24 other AVG volunteers boarded the Bloemfontein, a Dutch passenger liner that would carry them to the Malay Peninsula. Hill would board the Penang Trader in Singapore, bound for Rangoon, Burma.

Hill served aboard the Saratoga for about a year, flying the Douglas TBD-1 Devastator, before transferring to the East Coast and the USS Ranger (CV-4). He would be initially assigned to Bombing Squadron Four (VB-4), with Ed Rector and Bert Christman, schoolmates from Pensacola. When the squadron eventually split into two scouting squadrons—VS-41 and VS-42—Hill, Rector and Christman were part of VS-41.

The primary mission of the Ranger, with the Atlantic Fleet, was neutrality patrol operations off the coast of Europe, for which Hill would fly the SB2U Vindicator. Since the U.S. wasn’t in the war yet, Hill said they were “another set of eyeballs for the British.”

“We escorted the convoys making up out of Bermuda, carrying them over to the Azores,” he said. “We’d report anything we saw, like German submarines and hostile ships.”

On one patrol, Hill spotted two submarines and a tender.

“We called it out, and in the next go-around, a British heavy cruiser shot the tender,” he recalled. “Big oil slicks were everywhere, so I assume they dropped a lot of depth charges there. Another one we picked up was the San Adolfo, which was of Spanish registry. The Spanish ships were getting fuel from Spanish Guinea, in West Africa, and giving it to the Germans, otherwise they couldn’t have had the legs to operate in the Atlantic; they wouldn’t have had the range.”

Because of the Ranger’s notification, the Royal Navy was able to capture the San Adolfo.

An introduction to the AVG

While enjoying shore time in Norfolk, Va., Hill, Christman and Rector had a meeting that would drastically change their lives.

By the end of 1940, Japanese Zeros had destroyed 111 Chinese aircraft, with no losses, and controlled two-thirds of China. China’s Russian-supplied aircraft were so poor in quality and performance that they were withdrawn, resulting in the lack of an air force.

China’s Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek turned to Claire Lee Chennault, a retired U.S. Army Air Corps captain, as his military aviation advisor. Chennault formulated a plan that would call for the Presidential Liaison Committee to supply 500 pursuit planes, 150 trainers and 10 transports for China’s defense. President Roosevelt knew the U.S. had to help China, but because the U.S. wasn’t at war, any action could be politically devastating. In late December 1940, he signed a secret executive order, authorizing 100 planes and 300 men to defend China covertly. The order authorized military pilots and ground crew members to resign their commissions and serve in the new American Volunteer Group.

Chennault spoke to Gen. Henry “Hap” Arnold, chief of the Army Air Corps, about supplying 100 Army pilots with 500 hours of pursuit experience.

Tex Hill claimed P-40 #48 as his, after soloing in the aircraft at Kyedaw Airfield, Toungoo, in the fall of 1941. When this picture was taken, shark’s teeth hadn’t yet been painted on #48.

“If I gave you that many men with that kind of flying time, it would fold up my entire pursuit section!” barked Arnold.

The War Department predicted the AVG would last two weeks. But Chennault was confident and sent recruiters to every major Army Air Corps base and naval air station in the country. After Hill, Rector and Christman returned from an early morning flight in Norfolk one day, a recruiter told them of the search for pilots.

When Hill realized he could be sent to Burma, he was immediately interested, particularly after all the stories his parents had told about the Far East.

“Since I was born in the Far East, I wanted to get back over there,” he said. “I had even put in a transfer to the Houston (a heavy cruiser on patrol in the western Pacific). I was very lucky it didn’t go through, because the Houston was sunk.”

Because of Japanese blockades, the Chinese could get supplies only two ways: over the “Hump”—the chain of Himalayas between India and China—or by land, up the Burma Road. Fighter pilots were needed to patrol the Burma Road, keeping it open to traffic.

Volunteers would resign their commissions and operate as employees of the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company.

“Bill Pawley, who had been the Curtiss representative in China for many years, was head of CAMCO,” Hill explained.

Discharged from America’s armed services, they would be flying and fighting for the Republic of China. The Chinese government would pay their salaries through the civilian agency.

“We loaned the money to the Chinese and the Chinese paid Pawley,” Hill explained.

The contracts signed by the men stated their jobs were maintaining and test-flying aircraft. Rector thought that being “mercenaries” sounded exciting. Before they could hear anything further, however, Hill and his air group would board the Yorktown for an Atlantic cruise, in an effort to strengthen the fleet’s presence there.

At the end of the month-long patrol, the three men joined others who wanted to learn more. AVG squadron leaders would receive $750 per month, flight leaders $650 and wingmen $600. In most cases, the pay was considerably higher than that of the Army Air Corps. Although it wasn’t in the contract, the Chinese government had agreed to award a bonus of $500 for every Japanese plane shot down or destroyed on the ground. The men were also told that if they were discovered fighting the Japanese, the U.S. leadership would deny knowledge of the AVG’s existence.

“Seven men from my ship volunteered to go,” Hill said.

Following an attempted night intercept of Japanese bombers on Dec. 10, 1941, Tex Hill landed “long” in #48. The P-40 left the apron, bouncing over broken ground and crashing through undergrowth before the aircraft came to a stop.

As the number of AVG pilots began to grow, Chennault secured 100 P-40B Tomahawk fighters. Originally designated for the British, who now considered them obsolete, the Curtiss Corporation was eager to provide them to Chennault’s renegade operation.

“They cut a hundred P-40s off the line, with the assurances that the British would get an upgraded version,” Hill said. “They had British guns, which were a little different caliber than we used; our guns were .30 caliber and theirs were .303.”

In June 1941, AVG volunteers began to gather at the Bellview Hotel in San Francisco. In late July, Hill and 24 others boarded the Bloemfontein, a Dutch passenger liner which would carry them to the Malay Peninsula. Hill would board the Penang Trader in Singapore, bound for Rangoon, Burma.

Welcome to Burma

When Hill arrived in Toungoo in September 1941, about 150 AVG members were already there.

Hill’s new home, Kyedaw Airfield, owned by the British, offered barracks, a pilot’s mess, an operations building, a dispensary, a 4,000-foot unpaved runway and hangars. When faced with the insects, heat, humidity and mold, some of the men quickly decided the job wasn’t for them.

Hill was curious to meet Chennault, a fellow Texan, who had strongly voiced his opinions about airpower, resulting in ostracism by his peers and superiors in the Army Air Corps. Hill would get his chance when the newly arrived members were directed to his office their first morning in Toungoo.

“He was a very dynamic person,” said Hill. “The first time you met him, you got the message loud and clear that he was a no-nonsense guy who really knew what he was talking about. You immediately had a lot of confidence in him. He never used a lot of verbiage; he was straight to the point, mission-wise. He was a wonderful person, very loyal to the people who worked for him, and he was probably a real genius; he was way ahead of his time. That’s what upset a lot of the old guard, set in their ways, not able to change their minds, like, ‘Don’t confuse me with the facts, when my mind’s made up.'”

L to R: John Alison, Maj. Tex Hill, Ajax Baumler and Mack Mitchell, at Kunming in July 1942, pose in front of a P-40 bearing the original 23rd Fighter Group logo, a Disney tiger wearing an “Uncle Sam” hat, tearing through a Chinese Sun.

Hill’s instruction included aerial tactics and five hours of familiarization with the P-40B. At first, 37 pilots shared 13 planes. During training, the AVG would lament three deaths within a six-week period.

As more aircraft arrived, Chennault formed the men into three squadrons.

“The 1st Pursuit Squadron was nicknamed the ‘Adam and Eves,’ the 2nd ‘Panda Bears’ and the 3rd ‘Hell’s Angels.’ Most of the guys in my squadron, the Panda Bears, were Navy guys,” Hill recalled.

Jack Newkirk, from New York, was Hill’s leader.

First victories

By October 1941, Chennault was convinced that the Japanese intended to move on Rangoon. Through intelligence reports, he knew the Japanese were building up forces along the Indochina/Thailand border. The U.S. had put an oil embargo on Japan, causing the country to look for other petroleum supplies. Oil was plentiful in Burma.

The AVG began reconnaissance flights over potential Japanese bases in Thailand, less than 60 miles from Toungoo, searching for evidence of enemy activity.

By November, all of the nearly 300 AVG members had arrived. That month, a magazine pictured a plane with shark’s teeth painted on the engine cowling, providing inspiration for the men of the AVG. Their own planes were soon decorated similarly.

By early December, accidents had reduced the aircraft inventory to 79—62 in commission and 17 waiting for repairs. A lack of tools and spare parts hindered the ground crews, but they would become accustomed to finding ways to keep the aircraft flying.

It was Dec. 8 in Burma when the AVG members heard that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. They soon learned that Japan had hit other targets, including Wake Island, Guam, Luzon, Malaya, Hong Kong and Singapore. Japanese troops had also streamed into Thailand.

Fearing a raid aimed at eliminating the AVG, Chennault directed Hill and the others to take immediate precautions, including setting up an alert roster, beginning regular patrol flights, installing an air raid siren and blacking out the field.

On the move

Thailand’s surrender to the Japanese eliminated the only land barrier between Japanese forces and Burma. The 3rd PS headed for Rangoon on Dec. 12, to support the British based at Mingaladon Airfield. The 1st PS and 2nd PS left six days later, crossing into China and setting up at Kunming.

“We moved those two squadrons overnight,” Hill recalled.

Hill was amazed at the devastation at Kunming.

Tex Hill greets Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, arriving at Hengyang to give the brand-new 23rd Fighter Group a “pep talk.”

“The Japanese had been bombing Kunming for years, with no military objective—just bombing right into the people,” he said. “That was my first indication of war, seeing all those dead and wounded people, with arms and legs blown off. It was terrible.”

Chennault arranged alert schedules and came up with the “Chinese radio warning net,” a unique warning system based on civilians reporting enemy aircraft to radio operators.

On Dec. 20, two mornings after their arrival in Kunming, Hill went to the alert shack to report for duty. While he made a quick run for coffee, air raid alarms went off. A standby pilot quickly took off in Hill’s aircraft, stranding Hill on the ground.

Hill counted eight pilots of the 2nd and 16 of the 1st, intent on intercepting the 10 bombers headed their way. Jack Newkirk and Jim Howard were leading four-ship flights of Panda Bears. Howard’s flight remained over Kunming, and Newkirk headed in the reported direction of the enemy planes. Chennault had ordered the Adam and Eves south toward Iliang, to cut off the bombers’ escape.

When the enemy spotted Newkirk’s flight, they jettisoned their bombs over the mountainsides and fled. Since the Panda Bears were now out of range, all headed back to base, except for Rector, who charged after the bombers, catching up with them just as the 1st Squadron pounced from above, and shooting one down. Of the 10 enemy aircraft, one lone bomber survived.

“They never came back again while we were there,” Hill said.

Trouble at Rangoon

On Dec. 23, a massive Japanese force descended on Rangoon. The AVG pilots didn’t realize an air raid was imminent until they saw their British comrades taking off. The unreliable British “alert system” around Rangoon was comprised of observers on foot, who carried mirrors to “flash” alerts back to the base. A prototype radar set detected reasonably well, in certain directions. The Hell’s Angels had to rely on the British for their cue to scramble, but the RAF pilots often didn’t inform them that an air raid was underway.

Despite the late start, the AVG launched 14 P-40s, downing six bombers and four fighters during the heated engagement. Pilots Neil Martin and Henry Gilbert were shot down, becoming the first two of the group to die in combat.

The bombs dropped on Rangoon that day resulted in 3,000 deaths and a mass exodus.

That Christmas, the Hell’s Angels defended themselves against Japanese bombers and fighters. They were able to force down 13 fighters and 15 bombers, without any casualties. The AVG also got their first ace when R.P. “Duke” Hedman shot down at least five enemy aircraft.

The “Flying Tigers”

Lt. Col. Tex Hill married Mazie Sale on March 27, 1943, two weeks after noticing her at the First Presbyterian Church in Victoria, Texas.

Christmas 1941 wasn’t a joyous time for the men of the AVG or their country. The U.S. and its allies were struggling with a war on two different fronts and not doing well in either.

AVG victories often leaked out through the media as the only “good” stories coming out of the area. Sometimes the reports were embellished, but the AVG enjoyed the spotlight and fellow Americans relished the stories about its heroic exploits. One American-based Chinese newspaper ran a series of stories on the AVG pilots, enhancing the story by giving the men a nickname.

“The Chinese called us ‘Flying Tigers,'” Hill recalled. “I guess it was the aggressiveness of our first encounters. And, of course, the tiger is a symbol of strength.”

In late December, Chennault sent the Panda Bears to Rangoon to relieve the 3rd PS, down to 11 flyable planes. Intelligence reports indicated Japanese aircraft were amassing at many of the bases in Thailand. Thinking the Japanese probably wouldn’t engage them over the city yet, Chennault planned to put the AVG on the offensive.

On Jan. 3, 1942, Hill took part in a four-plane mission Newkirk was leading to strafe Raheng.

“Our first offensive mission was over in Thailand, right on the Burma border,” he said. “That’s where I got my first two airplanes. I almost got shot down myself; I got shot up pretty badly that day.”

They had planned an unexpected dawn attack over Tak, a small airfield, but they were the ones taken by surprise.

“I guess we forgot to look up,” Hill quipped. “They had some planes airborne, but there were a lot of them down on the field. Newkirk put us in a strafing formation. I wasn’t 50 yards behind Jim Howard, but a Japanese pilot got between us. I blew him out of the sky. Simultaneously, another guy made an overhead pass on me, just as I was pulling into a plane that was coming in. I got him, but his bullets stuck in my prop and threw it out of balance. The engine was running very rough; I thought it was going to come out of the airplane.”

That day, 33 bullets struck his fuselage and propeller.

Too close for comfort

Night raids became so regular that many of the exhausted AVG pilots now slept through them. The AVG was eventually invited into underground bomb shelters stocked by the Burma Oil Company, but Hill preferred his primitive quarters near an auxiliary field code-named “Johnny Walker.”

On Jan. 8, Hill, Rector and Merritt arrived at the airfield as Panda Bears Howard, Gil Bright and Pete Wright rose to intercept an early morning raid. Merritt stayed in the car, parked near the end of the runway, while Rector and Hill watched the battle nearby.

L to R: Flying Tigers Charlie Bond, Tex Hill and Ed Rector, received the British Flying Cross for gallantry in Burma from Lord Halifax, in Washington, D.C., in 1943.

Those on the ground had no idea that a spray of hydraulic fluid had blinded Wright, now struggling to land his aircraft. Rector and Hill watched in horror as the aircraft crashed into the vehicle where Merritt sat. Wright survived but Merritt didn’t.

Four days later, the Japanese launched the Burma Campaign.

Reinforcements arrive

The 2nd Squadron had lost several aircraft in mishaps and was down to 10 flyable P-40s. Also, five Panda Bears had been hospitalized with illness or shrapnel wounds. Eight members of the 1st Squadron, led by Bob Neale, a former shipmate of Hill’s, soon arrived to help.

Exactly one month after the first Japanese raid on Rangoon, Hill took a call in the alert tent advising that an enemy raid was incoming. His aircraft was undergoing maintenance and most of the other 2nd Squadron pilots were off on a mission. Hill took off in #57, normally piloted by Howard, and Frank Lawlor climbed into another available P-40.

They were soon attempting to break up a formation of 23 “Nates.” Hill downed one enemy aircraft in the 10 minutes before three other AVG members could join them. Before the Japanese fled, they had lost seven aircraft; Lawlor was responsible for four.

Less than two hours later, 10 of the AVG, led by Newkirk, combated a second echelon of enemy aircraft. This time, 31 bombers, escorted by almost as many fighters, converged on Mingaladon. The Flying Tigers shot down five bombers and four fighters, but lost Christman, who bailed out after his plane received several hits, making him an easy target for a Japanese fighter pilot who sprayed him with bullets, ending his life before he hit the ground.

Hill becomes an ace

On the day Hill became an ace, he was on a two-plane patrol with Bob Neale. Shortly after Neale spotted seven enemy bombers cruising toward them, Hill noted tiny specks in the distance, which he knew were fighters. The AVG members happily noticed that a pair of RAF Brewster Buffalo fighters was climbing toward the enemy bombers from another direction.

Hill and Neale dove on the bombers, each downing his target. Mingaladon, the enemy’s target, was just coming into view when Hill and Neale began a high-low tandem attack, intent on catching the bombers in crossfire. They shot up another bomber before the fighters caught up and four more P-40s joined the fray.

Hill flew back towards the remaining five bombers and fired, riddling one with bullets until it exploded in the air. A second later, shrapnel from the exploding bomber tore a large hole through his P-40’s left wing.

Before attempting to get his plane on the ground, Hill lined up a shot on a Japanese fighter speeding into the conflict and watched as the aircraft spun in.

Lt. Col. Tex Hill took command of the 23rd Fighter Group in November 1943. After this P-51A was assigned as his personal plane, his crew chief decorated it with shark’s teeth and painted “The Bullfrog,” his pet name for his wife, on the side of the engine

The Japanese would hit the base at Mingaladon continuously in their six-day effort to wipe out the Allies there. On Jan. 28—day five of the effort—16 Tigers battled over the field with 40 fighters, downing 10, with no losses.

Hill wasn’t in the air that day, due to a lack of planes, but he was the next day, as they battled 30 fighters. The Tigers took down 10 fighters, and Hill got his seventh victory.

When the Japanese halted their campaign against the AVG at Mingaladon, they went after Toungoo, which was empty except for planes requiring repair. A devastating attack destroyed the hangar, operations shack and three P-40s, as well as a handful of RAF Blenheim bombers.

Changes

Neale assumed command of the Adam and Eves after Sandy Sandell spun to his death while testing his repaired P-40, on Feb. 7.

The 1st Squadron had been in the process of relocating from Kunming to Rangoon, but that changed as Rangoon grew more dangerous. In late February, following the evacuation of the RAF, the Adam and Eves evacuated to Toungoo. The Panda Bears would soon return to Kunming. Members of the 3rd Squadron would be making a ferry trip to India to pick up badly needed P-40Es. By the time Rangoon fell, elements of all three squadrons were operating out of a base in Magwe, chosen as the regrouping point for AVG members in Burma.

On March 19, Hell’s Angels Bill Reed and Ken Jernstedt flew one of the AVG’s greatest missions. Nearing Moulmein on a reconnaissance patrol, they came across an unknown auxiliary airfield containing about two dozen enemy fighters. The men released 30-lb. fragmentation bombs, destroying 15 of the fighters, before speeding eastward to the main airfield, where they destroyed three bombers and a couple of transport planes.

The following day, the British bombed Mingaladon, now in Japanese hands, downing 16 more enemy fighters and 12 bombers. The Japanese quickly turned their fury on Magwe, caught by surprise due to the absence of a warning network. During a 25-hour period, they destroyed 11 British Blenheims, half a dozen P-40s and eight Hurricanes, killing a RAF airman and two Flying Tigers in the process.

It was time to move on, so the Flying Tigers started a 300-mile journey to Loiwing, a village nestled among the mountains on the Burma-China border.

A critical mission

The arrival from Africa of 12 P-40Es was a relief to the Flying Tigers. Each aircraft sported six deadly .50-calibers and underbelly bomb racks.

The death of Newkirk while on a strafing mission into Indochina marred the excitement generated by the new planes. His demise had occurred as he led a team of AVG pilots over two of Japan’s most active bases in the area—Chiengmai and Lampung—heavily fortified and well covered with antiaircraft emplacements. The night before, Hill had come across Newkirk, gravely writing letters.

Lt. Col. Tex Hill led the highly successful 1943 Thanksgiving Day raid on Shinchiku Airfield, Formosa, responsible for shooting 15 enemy aircraft out of the air and burning more than 40 bombers on the ground. This photo of the was taken just afterward.

“He had a premonition; he told me he didn’t think he was going to get back,” Hill recalled. “I said, ‘If you feel that way, I’d be happy to take that mission.’ He said no, he had to take this one.”

Hill, at the time Newkirk’s vice squadron leader, would soon find out part of what Newkirk had been writing.

“He asked Chennault to give me that squadron if anything happened to him,” he remembered. “Chennault moved me up and gave me the 2nd Squadron. Other guys were senior to me, but he wanted me to have it.”

Hill called on Rector to serve as his vice squadron leader.

The AVG had gathered a dozen P-40s at the base by the end of March. Eight RAF Hurricanes and a couple of Blenheim bombers would soon join those aircraft.

Since the AVG had moved to Loiwing, the group’s mission had changed. The Japanese armies were advancing northward from Rangoon, and the Allies were intent on defending northern Burma. At the request of Chiang Kai-shek, Chennault had agreed to provide needed air support to the Chinese armies, including missions over the front.

Hill was on a reconnaissance flight on April 12 with two other Tigers, patrolling between Pyinmana and Yedasho, when he spotted a bomber taking off at Toungoo, captured by the Japanese 55th Division on March 19. After strafing that bomber, Hill brought his P-40 around for a second pass to hit a second bomber, in the air. In the process, antiaircraft fire hit Hill’s aircraft, nearly tearing off the right wing, but he made it back to Loiwing.

On April 28, a day before the birthday of Hirohito, Emperor of Japan, the Japanese attempted a significant attack on the AVG base at Loiwing. In anticipation, Chennault had ordered 15 P-40s to patrol south past Lashio, in hopes of intercepting the bombers.

Hill took off that morning, leading a flight of five 2nd Squadron P-40s that would serve as top cover. Also in the air were 10 fighters of the 3rd Squadron, led by Arvid “Ole” Olson. Shortly after spotting Japanese planes coming toward them, they heard that a separate group of Japanese fighters was strafing the Burma Road at Lashio, crammed with refugees.

Olson and a handful of his flight diverted to stop the strafing. Hill soon counted 27 twin-engine bombers, followed by almost two dozen fighters. Hill and the four other Tigers concentrated on the fighters. Hill downed two aircraft, and other AVG members felled 14 more fighters. However, the bombers had been able to successfully bomb Loiwing.

The AVG’s effort had been valiant, but the Chinese ended up retreating and the Japanese troops captured Lashio. The Tigers there would move on to Paoshan, a small airfield just east of the Salween River, 100 miles into China, on the Burma Road.

Col. Tex Hill (right) converses with General Chow Chi-Rao, titular chief of the Chinese Air Force, and a Chinese-American Composite Wing commander during an inspection of the CACW at Kweilin, in 1944.

After capturing Toungoo, the Japanese 55th Division had advanced up the road to Mandalay, taking Pyinmana. The 33rd Division advanced through Prome and Magwe on the western route, and then halted on the southern border of the Yenangyaung oil flats.

When China’s 5th and 6th Army’s defense began to disintegrate, Japanese troops rushed to take their enemies from behind.

“Japan’s 18th and 56th divisions smothered their disorganized opponents as they drove to Mandalay and Lashio,” Hill said.

The huge gulf of the Salween River gorge, crossable by a single bridge, stood between the AVG and the Japanese ground troops.

“After Burma collapsed, the Japanese started driving,” Hill said. “They drove all the way up to the Salween River.”

Since Paoshan was a few miles east of the gorge, it was time for the Flying Tigers there to head back to Kunming, 200 miles to the east. On May 4, 51 Imperial Army bombers headed toward Paoshan, but decided that refugees on the Burma Road, hoping to reach China or India, were more appealing.

The Japanese returned the next day, but Hill and six other Panda Bears intercepted them. Over Paoshan, Hill shot down one of seven Japanese fighters, becoming a double ace.

That same day, advanced vehicles of the 56th Division reached the edge of the plateau west of the Salween River. Chennault and Chiang Kai-shek came up with a plan.

“The old man sent me down for the most important mission we ran,” Hill said.

In anticipation of their enemies’ advance, retreating Chinese troops had demolished parts of the suspension bridge spanning the Salween River.

“They trapped a lot of their own people on the other side,” Hill explained.

As Japanese engineers hurried to complete a pontoon bridge, the remains of the Chinese 66th Division tried to regroup on the gorge’s eastern slope. Chennault and Hill had earlier discussed dive-bombing extensively, and now the subject came up again. Hill and three other pilots were to aggressively bomb the Japanese at the Salween River, leading off with some dive-bombers to break up the road, blocking the exit of the Japanese. Chennault explained that Olson and three 3rd Squadron planes would be the crucial top cover. For the assignment, Hill chose Rector, Frank Lawlor and Tom Jones.

“We borrowed E models from the 3rd Squadron,” Hill recalled. “They were using our Tomahawks.”

The eight planes took off at mid-morning for the 200-mile journey to the gorge. The four P-40Es had clusters of 35-lb. fragmentation bombs under each wing and 570-lb. Russian demolition bombs along their centerline racks. Olson’s four P-40Bs climbed above the Panda Bears, to look out for enemy planes.

A weather front ended as they reached the gorge. As they descended in sunlight, they could see a column of trucks and armored vehicles trailing up from the river’s edge.

Hill sent his P-40 into a 60-degree dive, lining his aircraft up to target the top of the gorge. As gunfire began from below, he released his demolition bomb, and the men with him began their attack.

As they had planned, the attack had, at least temporarily, cut off the Japanese troops’ only escape. It also took away any cover they had. The Flying Tigers came back around, firing and dropping fragmentation bombs, killing troops, detonating ammunition stores and puncturing gas tanks, resulting in an inferno. When their guns were empty, the 3rd Squadron descended to contribute to a strike unequaled in success by any mission the AVG had yet flown.

“The Japanese had no place to go,” Hill said. “The gorge was sheer, almost 5,000 feet straight down. For three days, we really killed a lot of Japanese. They finally headed on down back the way they came and never tried to cross again. That was a turning point in the war. Had they crossed the Salween, China would have collapsed.”

The end of the AVG

The Flying Tigers needed airplanes; Hill, Duke Hedman and 10 Chinese pilots headed to India to bring back 12 Republic P-43 Lancers. Almost a week after they departed in a CNAC transport for Karachi, the Japanese bombed unoccupied Kweilin, the centerpiece of Chennault’s array of East China bases. After they returned six days later, Chennault decided it was time to move the AVG to East China.

The AVG was ready to move to the eastern airfields early in June. Peishiyi, 20 miles from Chungking, would serve as headquarters. For the time, the Adam and Eves flew to Lingling, the Panda Bears to Hengyang and the Hell’s Angels temporarily remained at Kunming.

When Hill returned from his ferry mission to India and reported to Chennault, he found out that the leader was concerned. The contract for the AVG would soon expire.

“There would be no more AVG after July 4, 1942,” Hill recalled. “That was deactivation day.”

Lt. Gen. Joseph Stilwell had promised to replace the AVG with a complete Army Air Corps fighter group, but by late June, barely 50 Army troops had reported to Chennault.

Chennault expressed his desire for Hill to stay. When Hill said he didn’t intend to leave, Chennault asked him to speak to the other squadron members about extending their contracts two weeks, to get the Army pilots up to speed on operations.

“I knew my squadron would stay,” Hill said. “Most of the 1st Squadron stayed. Most of the 3rd Squadron went home.”

Twenty-six pilots and 57 ground crew agreed to extend their contracts through July 18.

“At the end of those two weeks, they still didn’t have experienced people,” Hill said. “He offered us a spot commission; five pilots and about 22 ground personnel took it. We activated the 23rd Fighter Group.”

The four other pilots who had agreed to accept induction into the Air Corps and stay in China indefinitely were Rector, Bright, Charlie Sawyer and Frank Schiel.

By July 4, Hill was a double ace credited with 12 1/4 victories. The Flying Tigers had shot down 299 Japanese aircraft and destroyed another 240 planes on the ground, while losing only four pilots in aerial combat. A dozen of their P-40s had been shot down and 61 had been lost on the ground.

On the day the AVG was deactivated, the China Air Task Force came into being, made up of the remaining Flying Tigers and the newly arrived Army Air Corps personnel. It included the 74th Fighter Squadron, commanded by Schiel, located at Kunming; the 75th Fighter Squadron, commanded by Hill, at Hengyang; and the 76th Fighter Squadron, commanded by Rector, at Kweilin. The squadrons were part of the 23rd Fighter Group, which also included the 16th Fighter Squadron, stationed at Lingling, and the 11th Bombardment Squadron, equipped with a handful of B-25 bombers.

Col. Robert L. Scott—who would later write “God is My Copilot”—would command the 23rd Fighter Group. He would take over the group the same day Hill was promoted to major.

Commanding the 75th FS

Hill got his first victory as commander of the 75th Fighter Squadron on July 6, downing a “Nate” fighter while escorting B-25 bombers headed for Canton.

A frequent mission of the CATF fighters was strafing river-going vessels. When the 11th BS decided to hit the staging area of Kiukiang, Hill went along, although he hadn’t been feeling well. They scored direct hits on docks, warehouses and rail yards over the target, but one of the Mitchells suffered a direct hit from antiaircraft, and dove into the Yangtze River below.

A Japanese ground patrol hastily made its way toward the crew, which had bailed out safely and touched down near the river. Hill had spotted them and was soon making several strafing passes, giving the crewmen time to escape. On the way back to the base, Hill and the others in his flight also worked together to sink a small destroyer on Poyang Lake. Hill received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions that day.

After the mission, Hill couldn’t figure out why he was so tired and getting chills. His condition would continue, although some days he felt worse. During that period, he leaned on John Alison to help with day-to-day operations. Chennault had invited Alison and eight other AAC P-40 pilots of the 51st Fighter Group’s 16th Fighter Squadron to China for training in late June. Although it hadn’t been the plan, he’d decided to keep them and sent them on to Lingling.

Hill’s mysterious illness didn’t prevent him from earning a Silver Star for a successful bombing mission he made in July, in the early morning hours, on the docks at Hankow. Later that month, the Japanese stepped up their effort to drive the Americans from the East China bases, beginning with a battle over Hengyang.

Hill and Chennault had discussed a strategy they now planned on enacting. Two pilots would be needed, and Hill picked Alison and Capt. Albert “Ajax” Baumler.

When Baumler had reported to the 75th FS, Hill hadn’t been sure if he’d work out. Chennault had called him about the “Foaming Cleanser,” saying that the ace from the Spanish Civil War had threatened to shoot an AVG crewman who didn’t want to stay at a bar and drink with him. Chennault said he wouldn’t need to deport the excellent combat pilot if Hill took him.

After the two met, Hill agreed to take Baumler and Baumler agreed to refrain from drinking whiskey. Now, under a moon that was almost full, Baumler and Alison got into the air, Alison climbing to 12,000 feet and Baumler to 9,000, waiting to trap the bombers between them. The plan worked, and Baumler and Alison each downed two bombers above the field.

Alison’s plane had been badly damaged, however, and rather than crashing on the field, he headed for the Siang River, as Hill watched in horror. Hill was relieved the next morning to find out that the Chinese had fished his friend out of the river alive.

That morning, 27 fighters and 34 bombers headed for the field. Hill and 10 other P-40 pilots rose to meet them. Hill would later find out that the aircraft he dueled with that day and shot down was a Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa (“Oscar) fighter-interceptor. Three waves of attackers hit the field, causing the P-40s to divert to Lingling for a safe landing.

Shortly after that battle, Hill flew to a hospital in Chungking. Finding out he had malaria, he flew on to Chengtu, 150 miles northwest, where he would stay with a missionary family and receive quinine treatments.

During the three weeks Hill was gone, Chennault pulled the group back. With only a few gallons of gas and a meager number of operational aircraft, the 23rd couldn’t effectively operate from the advance bases. The 75th relocated to an airfield at Chanyi, northeast of Kunming, and the 76th joined the 74th at Kunming. The 16th Fighter Squadron withdrew to Peishiyi.

When more supplies came over the Hump, the 23rd FG could again take to the air. On Sept. 1, Hill and his squadron returned to Hengyang. After several battles with the Japanese, the 23rd was holding its three forward bases with only five flyable aircraft. Once again without sufficient supplies, Chennault ordered a pullback. It would be more than a month before the 23rd would have enough strength to return to their trio of forward bases.

On Oct. 25, Scott led 12 B-25s and 10 P-40s on a strike on Hong Kong. The pilots included Hill, leading an element of four off of Scott’s wing. In the opening seconds of the surprise attack, Hill shot down a Mitsubishi A6M Zero, bringing his total to 17.

That day, the CATF lost the only bomber they would ever lose to enemy fire. Six Zeros had attacked one B-25 that trailed behind. The bomber’s gunners brought two of the enemy aircraft down before it plunged to earth. All the others made it back, after downing about 20 enemy aircraft.

As the battle raged on, ground crews stayed busy making sure that the aircraft in their care, when at all possible, were flyable. One night at Chanyi, hours of work was destroyed—and it wasn’t by the Japanese.

Baumler had fallen off the wagon. While drunk, he had taken a P-40 for a short ride before coasting down the runway. Just as those watching breathed a sigh of relief, he turned the P-40 around, taxiing back down the runway at full power, before ground-looping into a row of seven just-repaired P-40s.

Three of the P-40s would have to be repaired again. Hill wasn’t sure what to do about the repentant Baumler, who recalled nothing that had happened. But Hill needed every pilot he had, and Baumler had already shot down six Japanese aircraft while in China. Hill and Alison talked it over, deciding to write the incident up as a “taxi accident.”

By that time, Hill, still battling his infirmity, wasn’t spending as much time in the air. Hill had received orders to take a leave in the States, and Chennault had requested he not participate in many of the most dangerous raids. Alison would take over the 75th.

In early December, Chennault held a farewell dinner for Hill and Rector, also going on stateside leave. The next day, the two friends boarded a Douglas C-47 transport.

Love at first sight

When Hill arrived in Miami on New Year’s Eve, he was a national hero. As one of the first USAAC pilots to return from the China-Burma-India Theater, he would be making a report to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Later, at the War Department in Washington, D.C., he described the operations of the China Air Task Force, sharing his observations of the capabilities of the Japanese and praising Chennault’s leadership abilities.

Hill had been promoted to lieutenant colonel by the time he returned to Texas for his well-needed leave. He’d decided it was time to buy land, and with his father’s help, he purchased a 1,600-acre ranch near Mountain Home, Texas.

He then headed for Orlando, Fla., to spend a few weeks at the Air Force Tactical Center. There, pilots who had recently returned from combat checked out in the latest fighter aircraft, equipment and weapons, and passed on their combat knowledge.

Hill’s next assignment would be as commander of the Proving Ground Group at Eglin Field in Florida. A division of the Army’s Proving Ground Command, commanded by Maj. Gen. Grandison Gardner, the group tested prototype aircraft and compared airframes.

Two weeks after taking command of the group, Hill flew a P-40L from Eglin into the little airport in Victoria, Texas, for a weekend visit with his family. His life would be changed forever during a sermon given by his brother Sam at the First Presbyterian Church. It wasn’t the preacher’s words that Sunday morning that caused the change; it was a blue-eyed, chestnut-haired beauty sitting in a pew across from him.

Hill was instantly smitten. Nineteen-year-old Mazie Sale had plenty of beaus, but on March 27, 1943, two weeks after they’d met, the couple married. They honeymooned in San Antonio and then were off to Washington D.C., where Hill was again to report to the War Department.

Once back in Florida, Hill began getting familiar with his new unit and its airframes, checking out in the new models of the P-40, Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Bell P-39 Airacobra, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, British Spitfire and the North American P-51 Mustang. He also checked out a few bombers, including the Douglas A-20 Havoc, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Consolidated B-24 Liberator, North American B-25 Mitchell and Martin B-26 Marauder.

The 14th Air Force

In early November, Chennault asked Gardner to release Hill. By then, the CATF had disbanded, after destroying 149 Japanese aircraft, while losing only 16 of its own. Chennault, now a major general, was commanding the 14th Air Force.

While Hill enjoyed his job at the Proving Ground, he was ready to return to China. Before he did, he passed his command to Rector.

Hill would head the 23rd Fighter Group, now under Col. Casey Vincent, commander of the East China Task Force (Forward Echelon), responsible for all operations east of Chungking.

Headquartered at Kweilin, the 23rd FG once again consisted only of its three original squadrons. The 74th remained at Kunming to attack targets in northern Burma and escort 11th Bomb Squadron B-25s on missions. Major Elmer “Rich” Richardson led the 75th from Kweilin, the site of the 23rd’s headquarters. The 76th was split between operations at Hengyang and Suichwan.

Chennault also commanded the 51st Fighter Group, mainly supporting Rear Echelon operations to the west; the 16th, 25th, 26th and 449th Fighter Squadrons; and the 308th Bombardment Group.

Hill had arrived in time to lead the highly successful 1943 Thanksgiving Day raid on the airfield at Formosa. Thirty U.S. fighters and bombers—14 B-25s, eight P-38s and eight P-51As—attacked more than 200 Japanese bombers and fighters in the air and on the ground at Shinchiku Airdrome, shooting 15 enemy aircraft out of the air and burning unsuspecting bombers on the ground.

“We went across, right on the deck, just about 100 feet, to keep from being detected,” Hill said. “We went about 100 miles across the straits. When we got there, a transport was coming down. I dispatched a 38 that shot it down. The bombers were just coming back from some mission and they were in the landing pattern. I had the B-25s loaded with frags. They pulled up a thousand feet and dropped them. They had gasoline trucks, everything out there on the field to receive these people. When we left, there was something like 43 airplanes burning. They took a picture of it.”

That day, Hill became the first P-51 pilot to shoot down a Japanese aircraft. For his leadership of the raid, he received another Distinguished Flying Cross. Within a month of the raid, the 28-year-old was promoted to colonel.

In January 1944, when the Forward Echelon became the 68th Composite Wing, Hill assumed the duties of vice wing commander. He would also soon be heading to Hengyang to take over fighter operations in support of the defense of Changteh. The 75th was already there, and the 74th would be joining them.

On March 5, Hill and three of his pilots flew back to India to retrieve a flight of P-51Bs, equipped with extra fuel tanks and improved engines. That spring, Japan devised a strategy they hoped would force China into surrender. The plan called for a land supply route, stretching from Indochina to Peiping and running along the Hanoi-Peiping railroad. Part of the plan was to demolish the bases at Hengyang, Lingling and Kweilin, through which the railroad ran.

The first step of Operation Ichi-Go was the offensive from Burma toward the Hump bases in India’s Assam Province. By the middle of May, the Japanese had cleared the northernmost segment of the railroad, from Hankow to Peiping.

On May 6, Hill led 54 aircraft—including P-51s, P-38s, P-40s and B-24s—to hammer the Yochow staging areas. Hill had taken to calling his aircraft “Bullfrog,” his pet name for his wife. Now in P-51B bearing that name, he and the others with him engaged enemy fighters over Tungting Lake. Hill downed one “Oscar,” bringing his total victories to 18 1/4. Although he didn’t know it at the time, that would be his final aerial victory.

The 14th would need unprecedented quantities of fuel and supplies to counter the offensive and defend eastern China, but in April and May, the gasoline it received was a fraction of its allocated amount.

On May 26, the Japanese stormed Changsha. Following that, the 14th would pull together to hinder the troops and help the Chinese who were defending the city, frag-bombing columns of soldiers and making innumerable strafing runs.

On June 12, Hill set out in foul weather toward Tungting Lake, intent on showing a new member of the 74th Fighter Squadron how to strafe enemy targets. As they flew above the Siang River, Hill opened fire on a 51-foot motorboat, headed south and packed with Japanese troops. He sank the boat, but the troops had also fired on him, causing his canopy to fly off his aircraft. Blinded temporarily when his map flew in his face, he came within inches of plowing into the riverbank.

When Changsha fell six days later, the Japanese drove toward Hengyang. Two days later, they halted at Hengshan, a few miles from the airfield at Hengyang. Hill gave the order to evacuate for Lingling, but before they left, they bombed the airstrip.

As the Japanese surrounded Hengyang, the enemy also began to push northward from Canton, intent on eventually driving the two armies together.

The Americans hit the railroad that ran south from Changsha and the road that paralleled it, frag-bombing and strafing trucks and trains, preventing supplies from getting through. Chennault’s pilots also dropped food to those defending Hengyang, who resisted the Japanese for more than six weeks. The enemy broke through on Aug. 8.

In the 14th’s two-month, all-out effort, they had flown more than 5,000 sorties, shooting down more than a hundred enemy planes, and they had burned or sunk a thousand boats and destroyed 500 trucks. In the process, they had lost 43 aircraft and almost as many pilots.

Hengyang’s demise signified the collapse of the warning net for Lingling and Kweilin, resulting in the eventual evacuation of both those bases. Before the last men left at Kweilin departed for Liuchow, on Sept. 14, they demolished the base.

The 74th Fighter Squadron was now under John “Pappy” Herbst. At Eglin, Hill had grounded the pilot for daredevil antics, but when he had heard Herbst was in China, he jumped at the chance to make use of his piloting skills. Hill had been right about his abilities. Herbst would end up a triple ace, with 18 official victories, and as far as Hill saw it, he was the greatest leader the 74th FS ever had.

Now, Herbst and his men moved 200 miles northeast, setting up operations at Suichwan, Kanchow, Namyung and Changting, a group of bases located in a pocket of Chinese-held territory behind the Japanese advance. For four months, the 74th and 118th Fighter Squadrons operated as guerrilla units from those bases, as the Japanese drove from Hengyang south to Canton.

Once again, Hill received orders to return to the States. He would be turning over the 23rd to Rector. Hill was to report for duty in Fighter Requirements at the new Pentagon.

Back in the States

On New Year’s Day 1945, at a pre-Rose Bowl brunch party, Hill had a serious discussion with Gen. Hap Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces. Hill bristled when Arnold voiced disappointment with the way things went in East China, since Chennault had promised the 14th could hold onto their airfields.

Hill responded that Chennault could’ve kept his promise, if they had the aircraft, pilots and supplies they needed. When he told Arnold that his fighter group had no replacement pilots, Arnold couldn’t believe it, stating that there were 3,500 surplus pilots in the AAF at the time. He also couldn’t believe that they rarely had new replacement aircraft. Hill would later be pleased to find out that Arnold had investigated what he told him, and, after finding it true, had flooded the China Theater with planes and equipment—although a little too late.

Hill’s desk assignment to the Pentagon was brief. After leave in Texas, he secured a group command of P-38s at Van Nuys. That, too, was temporary. He soon headed to Bakersfield to assume command of the 412th Fighter Group, the U.S.’s first combat group equipped with jet aircraft. The group consisted of the 445th Fighter Squadron, at Bakersfield, which was group headquarters; the 29th at Palmdale; and the 31st at Oxnard, being equipped with 20 P-59A Airacomets, America’s first attempt at a production jet fighter.

The group’s headquarters would later move to Santa Maria Airfield and then March Field.

“We had the YP-59, which was built by Bell,” said Hill. “They built only a few of them, but it was a start. It wasn’t a good tactical airplane. We went on up to the Century Series, but I left right after we got the P-80s.”

Hill said that at the time, “everybody wanted to get into the jet business.”

“I checked some people out illegally,” he chuckled. “I checked out a lot of people, like Dick Bong, who was killed very shortly after that. I checked him out in a YP59, but they had just come out with the P-80s, which were still experimental. He flew one down at Lockheed and had a flameout.”

As the group trained in Santa Maria, they didn’t know if they would return to the Far East, even though Hill had received a report date to deploy the 412th for combat. The dropping of the atomic bomb affected that order and the face of the war.

World War II had ended, and Hill’s thoughts turned to his ranch in Mountain Home. He applied for separation from the Army Air Forces, turned over command of the 412th Fighter Group to Bruce Holloway, and with Mazie, headed for his ranch at Mountain Home.

Home on the range—for a while

The Hills settled into a life of ranching at Mountain Home. Three months after the birth of Mazie Lee, on April 11, 1946, Hill resigned his commission.

Hill settled comfortably into the life he had dreamed about, but the livestock and the rugged lifestyle didn’t interest Mazie; she missed city life. It didn’t help that temperatures that winter were the lowest in over a century. As freezing rain turned into bitter cold and livestock dropped dead, Hill weighed his options. The weather and drastic change in lifestyle were only two of the reasons for his wife’s unhappiness. She expressed to her husband that he was “wasting his talents on a few goats.”

The lives of Tex and Mazie Hill changed again when a messenger braved the bone-chilling cold to make his way up the road to the couple’s home.

“General Knickenbocker, from Austin, was the adjutant general, and he sent a three-star Army guy to deliver a message to me,” Hill said. “He said the governor wanted me to take over the Guard unit.”

The Air National Guard was in its formative stages. The Texas branch encompassed five states—Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

“I accepted and had the 58th Fighter Wing,” Hill said.

Until the Texas Air National Guard received its federal recognition, his job was part time. Hill commuted by Beechcraft C-45 between his ranch and the Texas Air National Guard headquarters at Ellington Field in San Antonio. After receiving federal recognition, the 30-year-old would receive a commission as brigadier general.

When the Hills were able to move to San Antonio for good, they purchased a small home on Garraty Road in the Terrell Hills area, near Fort Sam Houston. But even as he commanded the Texas ANG, Hill anticipated the formation of the U.S. Air Force. He soon took the examination for a regular commission and resigned his National Guard commission.

By the time his commission was accepted, however, Hill had become involved in another project. Merian Cooper, Chennault’s former chief of staff, was now a Hollywood producer and had asked Hill to help him on three films directed by John Ford, one starring John Wayne.

Excited about the prospect, Hill signed a contract. The first movie was “Mighty Joe Young,” a story involving a family of gorillas. Hill would be traveling to Africa, in search of a baby gorilla.

When Hill left for the Belgian Congo, he assured Mazie that he would be back before she gave birth to their second child, due in the fall. His trip would make it impossible for him to report in time for active duty, so he obtained a 30-day extension. Complications resulted in the trip dragging into its third month; Hill missed his extended report date, ending his days of active duty service.

Once he’d returned, he decided he wasn’t interested in helping Cooper further, and asked that his contract be cancelled. With a new baby boy, David Lee Jr., born Sept. 17, 1947, Hill again took stock of his life.

His next project would be drilling oil wells. Hill, Wynn Miller (one of his former squadron commanders) and drilling expert Joey McCartney teamed to form Wildcats, Inc., an independent oil operation. Their investors included several of Hill’s friends from Hollywood, including John Wayne. After meeting in the late 1940s, Wayne had told Hill that he based his character, Capt. Jim Gordon in the 1942 film “The Flying Tigers,” on the famous ace. Hill and the actor remained lifelong friends.

Although Hill learned a lot about the oil business, the meager success of Wildcats didn’t provide enough capital, and the operation soon folded. Hill had better luck later when he acquired Old Rodriguez Field, which quickly yielded 20 barrels of oil, leading Hill to put down 37 wells.

A few years into the operation, Hill entered discussions with the ABC Oil Company, which specialized in secondary oil recovery., and was advised that his primary yield was most likely coming to an end. He’d need to make a significant investment to transition to secondary recovery. ABC offered to buy the operation for $100,000, and Hill eventually agreed.

The wells continued to yield primary oil. After recouping its investment, ABC sold the operation to Texaco, which forced another 1.4 million barrels from the wells.

Hill remained in the business, becoming a first-class field operator. He was also a devoted father. The Hills would welcome Ann Shannon in 1949 and Lola Sale four years later.

Mazie Hill had also found her niche in the business world. After passing her real estate exam, she rose to the top of her profession, eventually owning her own company and becoming the first female president of the San Antonio Board of Realtors. After selling her company to Charlie Kuper, she continued to work as a senior member of the Kuper Realty Company.

Back in the cockpit

Near the end of the Korean War, Hill accepted a commission into the active reserve as a colonel. He assumed command of the 8707th Flying Training Group, under General Jack Foster’s 8707th Wing, at Brooks Air Force Base.

The 8707th’s mission was to train a sudden influx of pilots in jet combat. At the time, the Air Force’s primary single-engine jet trainer was the North American T-28 Trojan. When the Air Force changed the group’s mission, the 8707th transitioned to the Fairchild C- 119 Flying Boxcar transport.

In early 1955, Hill began commanding the 433rd Troop Carrier Group, which flew the C-119, and later the C-5 Galaxy. In early 1957, he resigned his commission, ending his active military service.

That same year, dropping oil prices forced many independent operators out of the market. By then, Hill had drilled more than 100 wells and held the record for more oil and gas discoveries in south Texas than all other oil operators combined. He’d conducted joint ventures with Humble Oil (later Exxon), Mobil, Sinclair and many other independent firms. But he now found that his particular specialty, improving production, was in far less demand, and sold most of his assets.

Hill remained in a ready reserve status until 1968. His associations with Chinese officers and statesmen led him to help others open commercial doors into the Far East. When it became known that he was an “inside authority” on Southeast Asia, firms needing an expert consultant contacted him. For his new occupation, Hill made dozens of trips across the world throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Keeping in touch

Shortly before the end of World War II, George “Pappy” Paxton and others had successfully secured incorporation papers for the AVG. Many of those members, including Hill and Chennault, would gather in Los Angeles in May 1952, for the first Flying Tigers reunion.

By the end of the 1950s, the reunions were annually held at a resort in Ojai Valley, Calif. Others took place in New York, Taipei, San Diego, Mallorca and San Antonio. Hill was elected president of the Flying Tigers Association and the American Fighter Aces.

In December 1996, at the reunion in Dallas, surviving members of the Flying Tigers received Distinguished Flying Crosses and Bronze Stars from Gen. Ronald Fogleman, chief of the Air Force. It was the first time the Department of Defense had ever approved individual awards for the AVG.

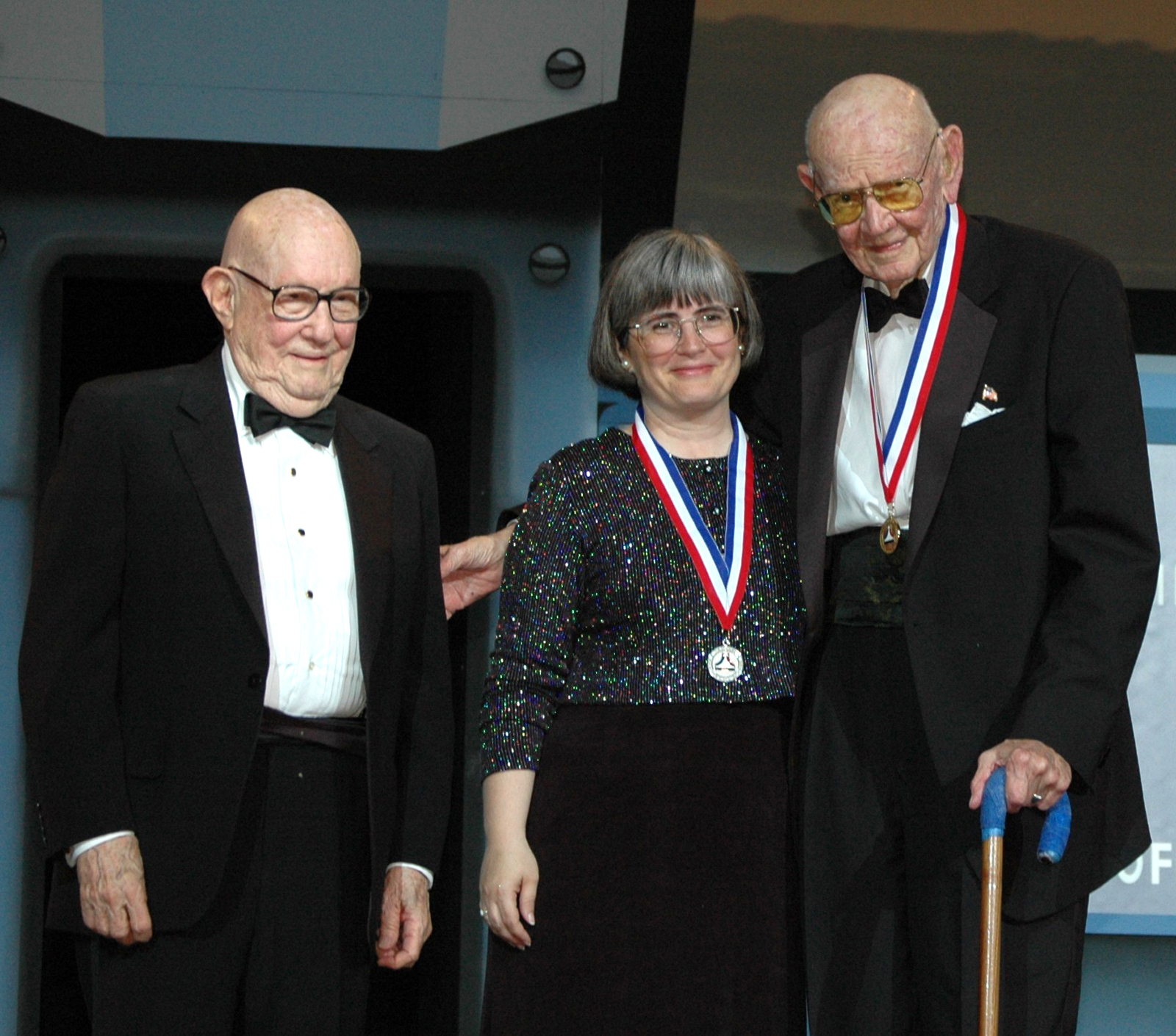

Hill’s many awards included the Distinguished Service Cross and Distinguished Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters. He was enshrined in the National Hall of Fame in 2006. It was fitting that he received his award from 2005 enshrinee Gen. John L. Alison, who had been present to witness many of his good friend’s shining moments.

Tex Hill’s complete history can be found in “Tex Hill: Flying Tiger,” published by Honoribus Press.

- NAHF President Janet E. Bednarek congratulates Brig. Gen. Tex Hill (right), presented his enshrinement award by Gen. John Alison (left).

- Brig. Gen. Tex Hill and his wife Mazie pose beside Hill’s enshrinement poster, prior to ceremonies in Dayton, Ohio, in which Hill was enshrined into the National Aviation Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2006.

- During the National Aviation Hall of Fame’s 45th annual enshrinement ceremony, Brig. Gen. Tex Hill received his enshrinement medal from Gen. John Allison, fellow Flying Tiger, longtime friend and 2005 NAHF enshrinee.

- NAHF Executor Director Ron Kaplan (in background) and Maj. George Dalton (right) watch as Brig. Gen. Tex Hill blows out the candles on the cake celebrating his 91st birthday.

- Members of the 8-229th Aviation Regiment out of Ft. Knox, Ky., flew six Apaches to Dayton for Brig. Gen. Tex Hill’s 91st birthday on July 13, 2006.

- The cover of “Tex Hill: Flying Tiger” features “Tigers in the Gorge,” a painting by John D. Shaw that depicts Hill leading the historic 1942 AVG battle at the Salween.

- Col. Tex Hill greets Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault upon his arrival in New Orleans from China, in 1945, just before the largest ticker-tape parade in the city’s history, in honor of Chennault.

- Gen. Henry “Butch” Viccelio awards the Distinguished Service Medal (second only to the Medal of Honor) to Brig. Gen. Tex Hill in Washington, D.C., in 2002.