By Bob Shane

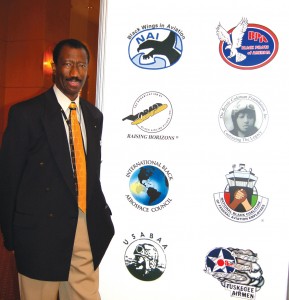

Brig. Gen. Leon Johnson is the board chair and managing director of the International Black Aerospace Council. This year, seven members including the Tuskegee Airmen held a convention together for the first time.

Highly respected and honored, the World War II black aviators known as the Tuskegee Airmen came from all over the country to Phoenix to attend their 35th annual get together. The 2006 Tuskegee Airmen National Convention was held at the J. W. Marriott Desert Ridge Resort and Spa from July 31 to August 5.

Nearly 100 of the revered octogenarians attended the convention. A few walked with canes or navigated through the resort on motorized carts, but many looked and acted much younger than their median 85 years of age. Their brilliant red or blue blazers signified chapter affiliations, and many wore baseball styled hats emblazoned with the words “Tuskegee Airmen” and patches in the shape of the red-tailed fighters they flew during World War II.

They came to enjoy the camaraderie of being with their wartime brethren, eagerly retelling war stories as if it were for the first time. They spoke of aerial dog fights in the skies over Europe, North Africa and the Mediterranean, or which plane was their favorite, the P-51 or the P-47, but mostly they talked about how much they loved flying. Those that entered the Tuskegee flight program all seem to have had the same common objective: simply to become a pilot. They wanted to fly and were prepared to die for their country.

L to R: Alex Anderson got to check out a mock-up of Roscoe Brown’s P-51 with the help of Tuskegee Airman Lt. Col. George Hardy.

Almost 1,000 African Americans won their wings at Tuskegee Army Air Field. While it was not their goal to be civil rights pioneers, in retrospect this proved to be one of the cards that history dealt them. For just as effective as the six .50 caliber guns on their red-tailed P-51s were in shooting down the planes of the German Luftwaffe, their success in combat was equally effective in shooting down racial barriers, ultimately helping to pave the way for the integration of the U.S. armed services.

This year’s convention was unique in that it marks the first time that Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. held a convention with six other black aviation groups, all of which are members of the International Black Aerospace Council.

“America’s seven black aviation organizations have joined together to showcase the accomplishments of blacks in transportation, aviation and aerospace,” said Brig. Gen. Leon A. Johnson, IBAC’s chairman and managing director. “Additionally, IBAC seeks to bring national attention to their goal of providing opportunities for youth interested in aviation careers where minorities and females have traditionally been underrepresented.”

This photo of George Hardy was taken in 1944 during pilot training at Tuskegee Army Air Field, Alabama.

IBAC is, in effect, a clearinghouse for the exchange of ideas and information for scholastic and employment opportunities for people of color in aerospace fields. There’s a big emphasis on youth.

“The kids must be shown what is available starting at the middle school level. We want to make sure that we don’t miss anybody and no one is missing opportunities,” said Johnson, a pilot who is also a flight training fleet manager with UPS.

Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. is a nonprofit organization whose goals are to perpetuate the activities and achievements of those Americans who served at Tuskegee Army Air Field or in any other projects stemming from the Tuskegee Experience between the years 1941 and 1949. It has 50 chapters in 28 states with almost 2,000 members. The membership includes 388 living original Tuskegee Airmen, of whom 130 are pilots.

The Organization of Black Airline Pilots, Inc., also a member of IBAC, was founded in 1976 to prepare young people for successful careers in aviation through education, mentoring and scholarship programs. OBAP sponsors Aviation Career Education camps, summer flight academies, career fairs and a Pilots in Schools program to educate minority and disadvantaged youth about careers in the aviation industry. The other IBAC co-convention members are the Bessie Coleman Foundation; Black Pilots of America; National Black Coalition of Federal Aviation Employees; Negro Airmen International, Inc.-Black Wings in Aviation; and the U.S. Army Black Aviation Association.

On August 2, a red-tailed F-16 display monument and park were officially dedicated at Luke AFB, in honor of the Tuskegee Airmen. The project was commissioned by the 944th Fighter Wing, an Air Force Reserve Unit based at Luke.

Captain Karl Minter, a flight manager and line-check airman for United Airlines, is the president and CEO of OBAP. According to Minter, “The Tuskegee Airmen were the trailblazers. They are heroes who left us the legacy of opening a career field that was previously closed.”

Through the example and mentoring of the Tuskegee Airmen, Minter strives to make the connection and influence kids to learn math and science and stay out of trouble.

Convention planners put together a full program of activities, including the dedication of the Tuskegee Airmen Airpark at Luke Air Force Base and the annual Lonely Eagle Ceremony, a military luncheon. Tuskegee memorabilia was available at an exhibit hall. The convention also included military leadership forums, a ride on a C-17 and an awards banquet.

Airpark dedication

L to R: Lt. Col. Lee Archer, Lt. Col. Robert Ashby, Col. Derek Rydholm (commander of the Air Force Reserve Command’s 944th Fighter Wing), Master Sgt. James Sheppard and Tech Sgt. George Watson helped to cut the ribbon during the dedication ceremony.

On August 2, the 944th Fighter Wing, an Air Force Reserve F-16 unit at Luke AFB, officially dedicated a red-tailed F-16 display monument and park in honor of the Tuskegee Airmen. The F-16’s tail was painted to resemble the P-51s flown by the black airmen during World War II.

The Tuskegee Airmen compiled an outstanding combat record, flying 1,578 total missions and 15,553 sorties. They destroyed or damaged 136 aircraft in the air and 273 aircraft on the ground. Flying as escorts for allied bombers, they had the unparalleled distinction of never losing a single bomber to an enemy fighter. The Tuskegee pilots often flew with the bombers, through enemy flak, all the way to the target. Their heroism and skill made them legendary.

Allied heavy bomber crews called them the “Red-Tailed Angels,” and would request them as escorts. Ironically, with fighter pilots’ faces being covered by an oxygen mask, many of the bomber crews didn’t know an all black fighter squadron was escorting them. They just knew they were escorted by the Red Tails.

L to R: Tuskegee Airman Charles McGee, 87, was accompanied by his son Ronald McGee for the ceremony at Luke AFB.

More than 50 Tuskegee Airmen attended the ceremony at Luke. They arrived in several buses, which were given a motorcycle escort from the convention hotel out to the base. Following the ceremony, which included a ribbon cutting and a missing man formation of four F-16s, the VIP guests were served lunch.

George Hardy: Just one example

Typical of the many individual stories regarding the lives of the Tuskegee Airmen is that of Lt. Col. George Hardy. One of the Tuskegee Airmen present at the event, the 81-year-old was awarded an honorary doctor of public service from Tuskegee University earlier this year.

In March 1943, 17-year-old George Hardy was sworn in. He went on active duty in July 1943, entering aviation cadet training at Tuskegee Army Air Field in December.

After graduating and receiving his wings in 1944, Hardy got 10 hours in his first fighter, the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk. At that point, he still hadn’t driven a car. He received additional combat flight training in the P-47 at Waterboro AAF in South Carolina. There, the black pilots had their own officers’ club and stayed on base since there was no place in town where they could socialize.

“My goal was to fly and I could put up with anything to get that done,” the retired lieutenant colonel said.

In March 1945, Hardy was assigned to the 99th Fighter Squadron, 332nd Fighter Group in Italy. He flew 21 combat missions over Germany. Following his return from overseas, he was discharged in November 1946.

This T-6 Texan II, a turboprop built by Raytheon, is used to train Air Force pilots today. It was part of a special aircraft display set up for the Tuskegee Airmen’s visit to Luke AFB. They trained in the original AT-6 Texan at Tuskegee Army Airfield.

Then in June 1948, he was recalled to active duty and assigned to the 301st Fighter Squadron, 332nd Fighter Group at Lockbourne Air Force Base in Ohio. After going to the Airborne Electronics Maintenance Officers’ School, he was transferred to the 28th Bomb Squadron, 19th Bomb Group on the Island of Guam, as a maintenance officer on B-29s. He was the first person of color in the 19th BG.

“My squadron commander would talk to me in the line of duty, but when we were in a social setting, it was as if I wasn’t in the room,” he said.

In 1950, despite his commander arbitrarily limiting his flight status, Hardy was able to fly 45 combat missions over Korea in the B-29. Between 1951 and 1962, he served in various armament and electronics maintenance squadrons in the Strategic Air Command, earned a BS in electrical engineering and received his command pilot rating.

In 1960, Hardy was a squadron commander in a KC-97 tanker unit based at Plattsburg, N.Y. Ironically, his commanding officer was the one he had when flying B-29 missions over Korea. This time, however, the commander had a positive attitude toward him. Some time later, after leaving the unit, Hardy got to see an evaluation the commander had given him. He was surprised to read, “George is the best of my six squadron commanders.” Over time, the barriers had come down and attitudes had changed.

Hardy went on to get a master’s in systems engineering-reliability. In 1970, he transferred to the 18th Special Operations Squadron as a pilot on an AC-119K gunship and flew 70 combat missions in Vietnam. He returned from Vietnam in 1971 and retired from the Air Force in November of the same year. Hardy had flown combat missions in three wars. He attained the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with 11 oak leaf clusters and the Commendation Medal with one oak leaf cluster.

General Chilton’s address

The “Red-Tailed Angels,” a painting by artist John Shaw, depicts a red-tailed P-51 of the Tuskegee Airmen escorting a lone B-24 bomber that has become a straggler after losing two engines.

General Kevin P. Chilton, the first astronaut to earn a fourth star, was the keynote speaker at an award luncheon. The veteran astronaut flew three space shuttle missions, and in June 2006, became the commander of the Air Force Space Command. He had words of praise and a thank you for the Tuskegee Airmen.

“You’ve played such an important role in our nation’s defense, and are still playing important roles,” he told the Tuskegee Airmen gathered. “It’s an honor to be in your company. It’s truly special to have so many people assembled here who have made, and still are making, such a big difference in the lives of our American youth. It’s a humbling experience to stand here in front of so many great Americans and so many great airmen.

He continued, “Today, you continue to serve through education and mentoring programs for our young people. In that light, the theme of this convention, ‘Reaching Our Youth—Ensuring the Future,’ is absolutely perfect. The spirit of Tuskegee is needed more than ever. For more than half a century, Tuskegee Airmen have inspired young Americans and pushed them to greater heights. Our youth need that inspiration more than ever. Because today we face a threat as dangerous, in the long term, as any terrorist. The threat we face is a growing intellectual deficit.”

Chilton went on to cite some ominous statistics, saying that the latest census on high-tech degrees is cause for concern. He said that 58,000 U.S. students graduate each year with degrees as scientists or engineers, compared to 80,000 in India, 200,000 in Japan and 800,000 in China.

United Captain Karl Minter is the president and CEO of the Organization of Black Airline Pilots Inc.

“Your message continues to be so important to America today!” he said. “The youth inspired by this convention will grow up and take the place of today’s airmen, and hopefully fill some of those science and engineering vacancies. If only one young person walks away from here inspired to serve, you’ll have done a great thing. I applaud you for reaching out to our youth and focusing your energy on our next generation. Sometimes we might ask ourselves if our youth understand and believe the American dream. I don’t think we can ever beat that drum enough. I think another important question to ask is, ‘Do our youth understand all the possibilities?'”

Chilton used his personal experience growing up in Los Angeles to illustrate how important it is that the youth of today know what opportunities are available to them.

“It wasn’t long ago that I didn’t understand all the exciting opportunities available to me,” he said. “I grew up just a mile from LAX and the school I went to was just past the runway. It was so close, we had to use sign language every two minutes when a plane would come flying overhead and drown out the teacher. From living there, I knew I wanted to be a pilot, but I didn’t know how I could ever achieve my dream.”

He said he found out quite by accident.

“During the summer, we would take any chance we got to go to the beach. Anytime word got out that one of the moms was going to the beach, about twenty bikes would descend on the house to catch a ride. Well, one day we got word my best friend’s brother was home on summer vacation and heading that way. So, of course, a swarm of bikes descended on his house.”

L to R: Michael McNeil poses with Robin Petgrave, the founder and director of Tomorrow’s Aeronautical Museum, and record-setting pilot Jonathan Strickland.

He said that as they drove, he asked his friend’s brother about what he was studying.

“It turns out he was a cadet at the Air Force Academy,” he recalled. “After he explained, I asked him how much it cost and he said, ‘Nothing. In fact, they pay you!'”

Chilton said that’s all he needed to hear.

“I often wonder what would have happened if I didn’t jump in the car that day,” he said. “Or, if instead of living one mile from LAX, I lived ten miles north. Would I have had the same opportunities? Would I have been able to realize the American dream? Right now there are young people out there just like I was. They’re searching for knowledge and possibilities. We can’t leave it to chance; we have to reach those young people living ten miles away from the airport and everywhere else too.

L to R: Tuskegee Airman Dr. Charles A. Hill Jr. attended the luncheon at Luke AFB with his wife Gwendolyn Williams.

“I know one thing for certain though. The youth influenced and inspired by Tuskegee Airmen know full well the American dream and the opportunities available to them. Because of you, they’ve been given a rare glimpse into their limitless potential.”

Chilton said that a task this important couldn’t be left to chance, and added that the Tuskegee Airmen, Inc., was definitely on the right track in the area of reaching youth. He noted the importance of the Tuskegee spirit is and explained what it is.

“You can succeed with hard work and determination,” he said. “No one but the Almighty can tell you what you can’t do. Knowing that, coupled with making known to them the exciting possibilities that await them, will ensure our future.”

Marine Corps Captain Vernice Armour is a pilot of a Cobra helicopter gunship and the first African-American female combat pilot in the military. She showed youth, such as this group from Avondale, Ariz., how to build airplanes using candy and rubber bands

Chilton’s speech was a poignant reinforcement of what the Tuskegee Airmen are all about today—youth. Lee Archer, the Tuskegee Airmen’s only confirmed ace, told Airport Journals, “This is what I tell young people: ‘We ran the first leg of the race; now it is your turn.'”

A dwindling national treasure

Every year, during each national Tuskegee Airmen convention, there is a solemn event known as The Lonely Eagles Ceremony. It’s a tribute to Tuskegee Airmen who have passed away since last year’s convention. The roster of names is read and those in attendance who knew the person are asked to stand. A bell is rung in honor of each passing member. This year the bell tolled 53 times.

No one knows for sure how many Tuskegee Airmen are still alive. Of the 994 Black pilots who graduated from the Tuskegee training program, one estimate is that there could be as few as 100 alive today. One thing that is known is that the number is declining at the average rate of five per month. There was talk that this year could be the final convention, but a 2007 convention is scheduled to take place in Dallas.

This T-6 Texan II, a turboprop built by Raytheon, is used to train Air Force pilots today. It was part of a special aircraft display set up for the Tuskegee Airmen’s visit to Luke AFB. They trained in the original AT-6 Texan at Tuskegee Army Airfield.

Earlier this year, President George W. Bush signed into law a resolution that will make the Tuskegee Airmen recipients of the prestigious Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor that can be bestowed by Congress. The presentation is expected to take place inside the Capitol rotunda in Washington D.C. later this year.

- The flight crew personnel from Charleston Air Force Base accompanied The Spirit of the Tuskegee Airmen. This C-17 was used to take a group of Tuskegee Airmen on a local flight.

- Looking on are Tuskegee Airmen Roscoe Brown (left) and Lee Ashby (right) look on as Gen. Kevin P. Chilton congratulated 14-year-old Jonathan Strickland for becoming the youngest person to solo in a helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft in the same day.