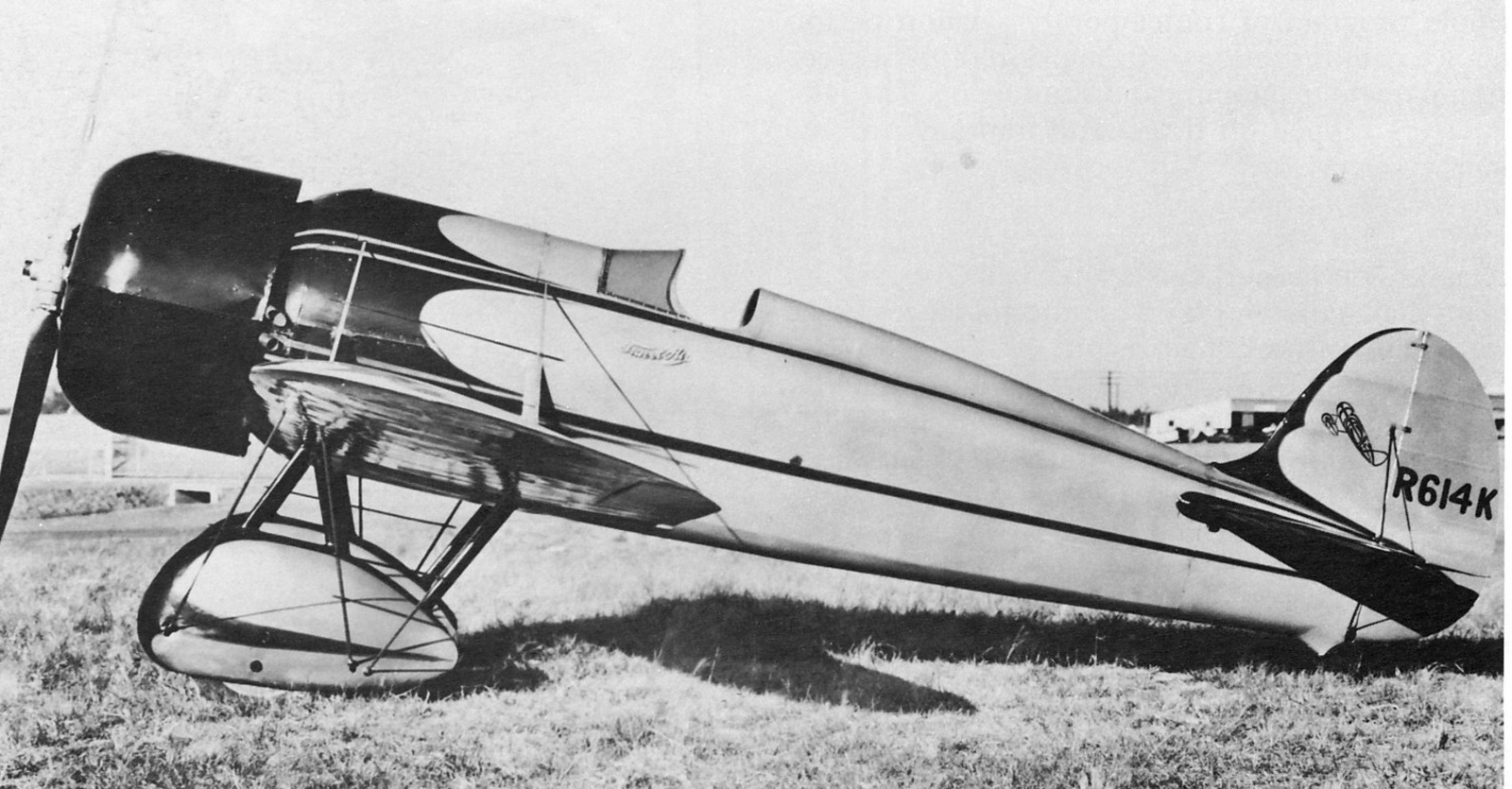

Travel Air engineers Herb Rawdon and Walter Burnham designed the Model R in anticipation of Walter Beech’s annual need for a racer.

By Daryl Murphy

Ten years after the end of World War I, the American public had become enchanted with the romance and excitement of the noisy, speeding machines locked in aerial battle. The government was more realistic; it saw little urgency for rapid aviation development during the postwar years. Military aviation had made design strides; its airplanes had won all eight Pulitzer Trophy races and two successive Schneider Trophy events. But by the late 1920s, the designs were becoming counter-evolutionary. Their one-off racers were biplanes powered by the two or three available liquid-cooled V-12s of about 400 horsepower, and could fly as fast as 250 mph, but most of the first-line pursuits still operated in the 150-170 mph range.

In the commercial market, aircraft producers were struggling. Their biggest sales competition was with the thousands of surplus trainers that had flooded the market in 1919. The only affordable power plants on the market were leftover OX-5 and Hispano-Suiza V-8s. Not many cash-strapped operators were willing to pay for what the engine designers were offering.

Between 1921 and 1928, while military pilots were flying at twice the speed of their older aircraft, the civilian closed-course speed record had risen a paltry 43 mph. Only when organized races became national events did the prospect of fame and its accompanying fortune move civil aircraft designers. Dozens of smaller prizes were offered to air racers, based on engine or weight formulas, but the big-bore, unlimited, free-for-all speed dashes always got the major money and all the newspaper ink.

Civil manufacturers didn’t have the resources to compete with the government and its expensive equipment. Then something happened to spur the worldwide development of the next generation of aircraft: the Wright Whirlwind and Pratt & Whitney Wasp, the first relatively high-power and reliable power plants, were introduced in the mid-1920s. Suddenly, designers had access to guaranteed horsepower right out of the crate. It had its price, but it was available to one and all. With a little creative tuning, innovative racers could compete at the same power levels as their Army and Navy counterparts.

At the Travel Air plant in Wichita, chief engineer Herb Rawdon and his assistant, Walter Burnham, knew that high speed wasn’t solely dependent upon horsepower—although that’s how the military kept winning the big races. If it looked like some upstart racer could be a little faster than an Army or Navy racer, the military would just install a bigger engine or soup up the one it had. Rawdon and Burnham had been mentally designing a racer in their spare time, but its actual construction was more happenstance than the product of deliberate planning.

Test pilot Clarence Clark reached 185 mph on an early test hop of the plane without its NACA speed ring. A few days later, with the cowl installed, the same power setting and altitude produced an astounding 225 mph.

Wichita was home to dozens of aircraft companies. Each spring, owners and engineers would suddenly realize that in only a month or two, the air racing season would begin, and they weren’t ready with their latest models. Travel Air boss Walter Beech, whose company was the world’s largest producer of both monoplanes and biplanes in the late 1920s, knew that his company’s success at racing would be one sure method of making even more sales.

Every year about mid-April, Beech would saunter into the engineering department and ask what new equipment was planned for the season. Other projects would be put aside as everyone concentrated on the high-priority project of converting a stock airplane to a racer. Deadlines were usually met, but more than once, an airplane’s paint was wind-dried en route to the opening event.

“All things being equal, I’d just as soon not go through this exercise next year,” Rawdon remembered saying to himself after the 1928 National Air Races. He decided to get his ideas down on paper and be ready when Beech got his annual itch.

The biplane-monoplane controversy hadn’t yet been resolved in 1928, but it looked like the two-wing faction—which the military headed—was winning. Monoplanes all over the country had been flat-spinning their way to the ground. Nonetheless, Rawdon decided on a wire-braced monoplane design with fixed landing gear. He admitted that the 1928 Schneider Trophy racers had a strong influence on his decision. He figured the company wouldn’t finance the project, so he and Burnham partnered on a part-time basis, after hours and in secret. They called it the Travel Air Model R (for racing).

A stress analysis was prepared based on existing Civil Aeronautics Administration requirements, and a gross weight of 1,750 pounds was assumed. An as-yet-undetermined radial engine would power the airplane. The design had a buried cockpit—one that barely interrupted its sleek, straight fuselage. Large, graceful pants covered its wheels.

As expected, Beech showed up in Rawdon’s office late in the windy spring of 1929. This time, the engineer was ready. His idea of a special racing plane intrigued Beech.

“How soon can we have it in the air?” was his only question.

Rawdon told him about 10 weeks—the amount of time remaining until the 1929 National Air Races in Cleveland. As it turned out, it was almost as easy to construct two airplanes for the event. A local builder and promoter had indicated he would have a 275-300 hp straight six developed in time for the race, so Rawdon and Burnham built a second R to accommodate the inline engine.

Early in 1929, Wright had debuted its new R-975 (J-6-9 Whirlwind). The 300 hp radial engine (it would actually put out 420 hp) was just what the Travel Air R needed, especially when tightly cowled in the newly developed NACA ring, which added precious mph to the design.

Douglas Davis flew NR614K to a 194.9 mph victory in the first Thompson Trophy race. It was the first time a civil airplane had defeated military pursuit racers.

The six-cylinder engine never materialized, but Gaston and Louis Chevrolet—the Indianapolis racing car builders who had sold their passenger car operation to General Motors—contacted Travel Air with an inverted, air-cooled six, called the Chevrolair. Although its power rating was only 250 hp, it generated immediate interest for the second racer.

The fuselages were constructed of welded steel tubes, the wings were wooden, and both were covered with plywood. Two sets of wings were built for the Wright-powered model—a shorter, narrower-chord version for closed course racing and a longer and wider pair for cross-country contests.

Beech, who wasn’t yet a monoplane convert, also ordered one special Travel Air biplane to be built for the races, powered by a J-6-7 Whirlwind and fitted with a NACA cowl.

The small group of people working on the R project was typically close-mouthed. The aircraft was being built literally behind closed doors, which was unusual at the time, especially during 100-degree Kansas summer days.

As more people became curious about the happenings at Travel Air, employees were inclined to talk less. An air of mystery developed, and then it turned to paranoia and inevitably to speculation. Predictably, the Wichita Eagle and rival Beacon newspapers began dubbing the project the “Mystery Ship,” which generated substantial amounts of national publicity. Walter Beech decided that if they kept the secret a little longer, it might be worth a lot of newsprint.

Early in August, two weeks before the start of the National Air Races, Travel Air’s number one racer, R614K, took to the air, minus its streamlined cowl and wheel spats. Test pilot Clarence Clark reached 185 mph in full-throttle, level flight. A few days later, with the NACA cowl installed, Clark got the surprise of his life when the same power and altitude produced 225 mph.

Walter Beech lined up Douglas Davis, Atlanta Travel Air dealer and noted air racer, to fly R614K for the National Air Races. Clark would handle the Chevrolair-powered R613K. The pair was so late leaving for Cleveland that the company artist didn’t have time to finish painting Clark’s airplane. As Davis left Travel Air’s field, he decided to buzz the gathered spectators. Diving toward the small crowd at an indicated 275 mph, he misjudged slightly and hit the ground with the landing gear. He flew on to Kansas City, where he would need to replace a broken wheel.

When the two racers arrived on Sunday at Cleveland, they taxied to a prearranged hangar, cut their engines and rolled inside. The doors were immediately closed and guards posted. The next morning’s newspapers were full of speculation about the airplanes from Wichita, now being called the “Mystery Ships.” When the racers finally rolled onto the turf for Monday’s competitions, the crowd went wild.

Throughout the week, the Rs dominated the spotlight. Davis won the Experimental Event, and J.O. Donaldson won the Rim of Ohio Derby. After his engine overheated, all Clark could manage in the Chevrolair R was a third in a 510 cubic inch race. The six-cylinder R was returned to Wichita on a truck, and its engine was later replaced with a Wright.

The final event of the 1929 Cleveland National Air Races was a 50-mile sprint race—the initial Thompson Trophy event—expected to be a closely fought battle between Army Lt. R.G. Breen, in a Wasp-powered Curtiss P-3A, and Lt. Cmdr. J.J. Clark, flying a Navy Curtiss Hawk. Five civilian aircraft entered the free-for-all, but none was expected to have a chance against the military’s fastest pursuit planes.

Shell acquired the third Model R. Jimmy Doolittle used it for an aerobatic routine during the 1930 Chicago National Air Races. Jimmy Haizlip flew it to a win in the 1,000 cubic inch event and placed second in the Thompson Trophy.

As expected, Breen shot from the starting line into the lead, but as he rounded the scattering pylon, Davis whizzed past the Army flyer and jumped into the lead, pulling steadily away. On the next lap, he began picking off the slower aircraft, one by one. But at the start of lap three, Davis cut inside a pylon. Under the rules, he had to go back and re-circle the marker or be disqualified. Realizing time was critical, Davis banked the R sharply, and momentarily blacked out from the G forces. Regaining his awareness, he didn’t know if he had made a complete turn around the missed pylon, so he circled it again. Back on the course, he upped his speed and went on to re-lap the entire field and finish more than 30 seconds ahead of Breen. He did it all in 14 minutes. Roscoe Turner’s civilian Lockheed Vega was third, ahead of Clark’s Navy Hawk.

Davis and the R614K had turned in an average speed of 194.9 mph—which included the time lost twice re-circling the missed pylon. It was more than 50 mph faster than any commercial aircraft had ever flown in a closed-circuit race.

Clarence Clark won two more races that summer in R614K: one in Sioux Falls, S.D. and another in Tulsa, Okla. In the fall, Doug Davis flew the R from New York to Atlanta, in a record four and a half hours.

Four additional “Mystery Ships” were built. Luminaries including Frank Hawks, Jimmy Doolittle and Florence “Pancho” Barnes flew three of them. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini ordered the last airplane, which was probably used to develop his country’s pursuit designs.

The triumph at Cleveland meant more sales for Travel Air, which at year’s end was acquired by Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Corp. It also marked the beginning of a new era in aircraft design. Until then, engineers had played a secondary role in creating aircraft, working from race pilots’ suggestions. From then on, engineers would point the way.

Despite the monoplane win in 1929, the odds-on favorite in the first Thompson Trophy race at Chicago in 1930 was still a biplane—a highly modified Curtiss XF6C-6 Hawk fighter, flown by Marine Captain Arthur Page. As expected, Page ran away from the field at the start, and began lapping back markers on his third lap. As Page rounded the home pylon on his 17th lap, however, the Curtiss rolled over and plunged to the ground. Investigation later indicated that the pilot was overcome by carbon monoxide in the tight cockpit.

Speed Holman in the Laird Solution biplane won the race, and Jim Haizlip, flying the Shell Oil Travel Air R, was a close second. Frank Hawks, in the Texaco No. 13 Travel Air R, dropped out early with fuel feed problems. Haizlip’s Travel Air might have won, but Shell Oil didn’t want to use the new leaded fuel blend furnished by the Ethyl Corp. (owned by Shell competitor Standard Oil). Haizlip used a lower-octane mixture of straight gasoline and slow-burning toluol. That cost him about 100 rpm, allowing Holman to win the 100-mile race by mere seconds.

The “Mystery Ship” may not have pulled off the repeat win, but it had made its presence known. In the 1930 race, the Curtiss had been the lone military entry, and the Laird was the last biplane to ever win the Thompson Trophy. It had started a revolution of development changes in aircraft, inspiring later American military pursuit designs; the triumphant Travel Air had helped end the American military’s reliance on biplanes and liquid-cooled engines.

And the sun had risen on the brief and brilliant Golden Age of Air Racing.