By Trev Martin

Shortly after acquiring his T-6, Steve Cowell was told that official Air Force records showed the aircraft to be the “only existing, authentic aircraft utilized exclusively by the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II.”

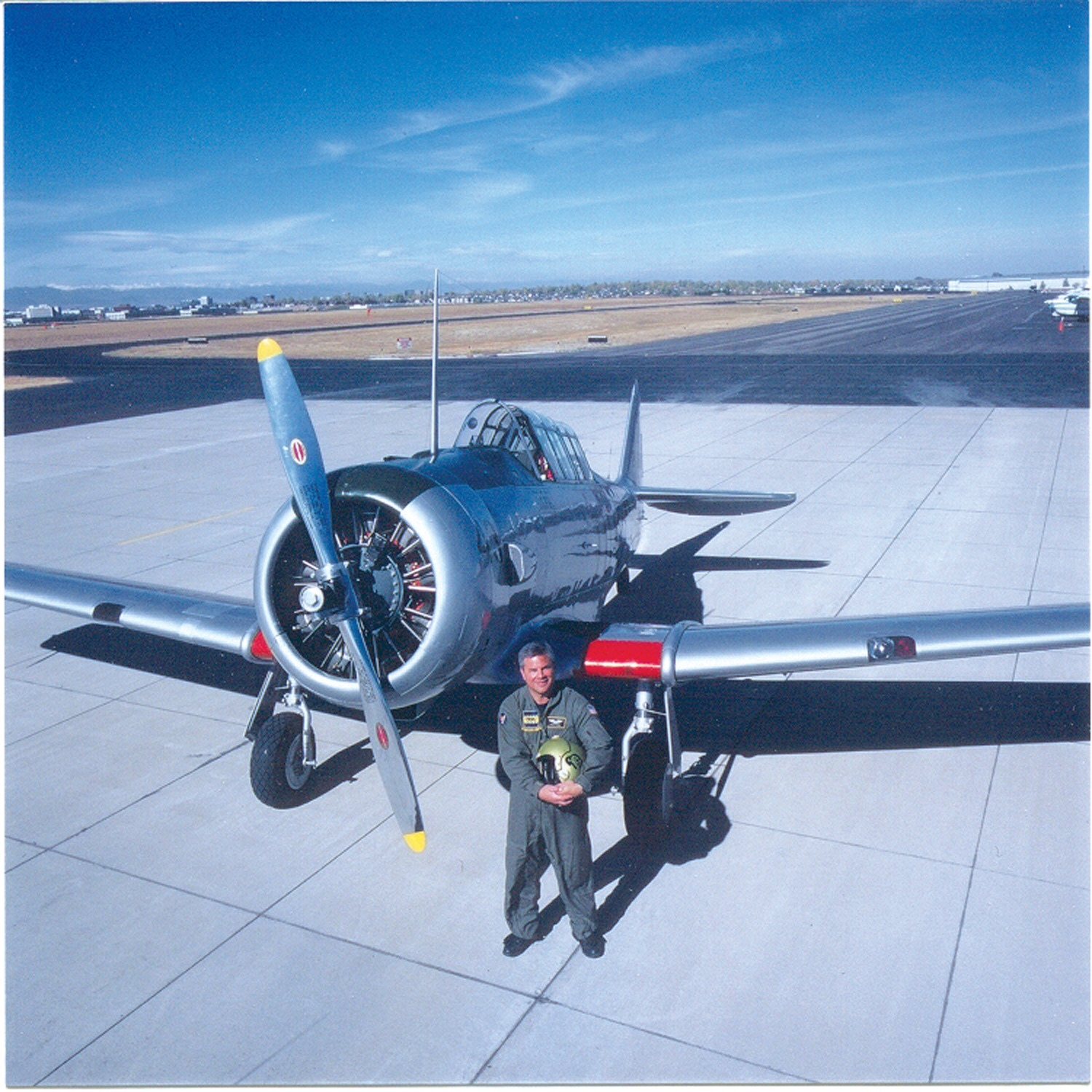

Steve Cowell pulls the “Double Vee” from its hangar at Colorado’s Front Range Airport and the sun hits the nose of the propeller, gradually shedding light on the flying artifact. Looking at this plane, it becomes apparent that this North American T-6 is a symbol for respect.

People and places, causations and incidental occasions shape into stories. Stories form history. Some history is documented and most of it is retold. However, with the gradual progression of time, a few stories are lost forever. But for Steve Cowell, a mortgage broker and the “accidental historian” of a historically significant T-6, this is a story that was destined to be retold.

When he first came to Denver in 1960, at the age of 7, Cowell had already caught the aviation bug. He remembers riding his bike out to Stapleton Airport to watch airplanes all day. His love for aviation continued through out his childhood.

“I remember cutting out the five dollar flight lesson coupons in Flying Magazine and riding over to Stapleton for lessons,” he said.

He found himself at a crossroads in high school, however.

It was tough,” he says. “I was trying to work, trying to study, and I couldn’t find time or enough money for flying lessons.”

“Taking a recess from flying lessons for a while paid off, eventually. After high school, he walked on at the University of Colorado as a kicker and defensive back for the football team.

“It was one of the most formative experiences that I’ve ever had because it taught me how to deal with adversity, and most importantly, it taught me never to give up. I was kind of a Rudy,” he said with a smile. “I was undersized and third on the depth chart, but because of my tenacity and perseverance, I was able to go to the Gator Bowl in 1972.”

Manufactured in Dallas in March 1943, this T-6 was delivered directly from the factory to Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. It’s now owned by Steve Cowell and based at Front Range Airport.

After college, he went back to what he loved and was so passionate about—flying airplanes. For several years before discovering the T-6 that would change his life, Cowell was a 727 captain for a small airline. He also worked for United Airlines as a consultant/instructor, teaching the ins and outs of the Boeing 737 to foreign student pilots from Russia and South America.

In 1997, he decided he wanted a plane of his own. He set his sights on one warbird in particular.

“I wanted a T-6,” he said.

That same year he saw a few T-6s that interested him, but nothing that really stood out. His search took him to Blue Earth, Minn., a small town near the Iowa/Minnesota border.

“From what I read initially about this T-6, I thought it might be a candidate,” he said.

It never entered his mind that this particular T-6 would send his life in a completely different direction. Cowell eventually purchased the aircraft, in August 1997, for $115,000 and paid Paul Redlich, an expert in T-6s, to complete a detailed pre-purchase inspection of the aircraft.

During the inspection, Redlich uncovered two serial numbers. One was from when the airplane was an original “C” model T-6, and the other was a more recent serial number from when it was converted to a “G” model. Cowell sent both of the numbers to the USAF Historical Research Agency for more background information.

When he got a phone call about five months after purchasing the plane from TSgt. Byrd at the agency, he was completely surprised by what he was told. It was information that none of the plane’s 10 previous owners had ever known.

A letter and a copy of the aircraft’s log confirming the unique history of the aircraft followed that phone call.

“According to the sergeant and official Air Force records, I had purchased the only existing, authentic aircraft utilized exclusively by the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II,” he said.

Manufactured in Dallas in March 1943, the airplane was delivered directly from the factory to Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. It stayed there until the base closed in 1946. It was converted to a “G” model in Downey, Calif., in 1951, and was first sold as a civilian aircraft in 1958.

In its early days as a “C” model, the aircraft was utilized to train the Tuskegee Airmen in the methods of aerial combat maneuvering, gunnery and close air support. Tuskegee Airmen of the 100th, 301st and 302nd Fighter Squadrons of the 332nd Fighter Group were trained in this T-6 before transitioning to the P-47 “Thunderbolt” and P-51 “Mustang.”

Cowell searched high and low to find out anything he could about the Tuskegee Airmen’s legacy and his airplane. In the meantime, he found a pilot who could train him how to fly the T-6.

“The aircraft wasn’t in great shape, but it was flyable,” he said.

Shortly after he began learning how to fly and control the plane, his treasure was almost taken away from him as quickly as it had been placed into his hands. In July 1998, a little less than a year after he bought the plane, the tailwheel steering cable lost tension just after a landing. The “Double Vee” was completely uncontrollable; all Cowell could do was hope for the best until it came to a stop.

He emerged relatively unharmed from the accident. Unfortunately, the same couldn’t be said for his aircraft.

“People were eager to buy it out of salvage, relatively cheap, and I did everything I could to save it from being totaled,” he said.

That’s when he found restoration specialists Ezell Aviation in Breckenridge, Texas.

“The cost of the complete restoration was more than I ever dreamed,” he said.

Sometimes, however, great sacrifices must be made to maintain history.

After the plane’s restoration, he renamed the T-6 the “Double Vee.”

“Double V,” also know as “Double Victory,” was a historical campaign waged by African-Americans during World War II. It stood for an uncompromised victory not only abroad against the Axis powers, but also at home against prejudice and racism.

“This plane was worth it,” Cowell said. “It needs to be preserved. It’s not just another T-6; it’s the only authentic Tuskegee Airmen aircraft in existence.”

The “Double Vee” has been featured on Discovery’s “Wings” program and in aviation publications around the country. Its won awards from the National Air and Space Museum, National Aviation Hall of Fame and the Experimental Aircraft Association. The Tuskegee Airmen are grateful for his contributions and perseverance with this significant aircraft. Tuskegee legends like Col. Lee Archer, the only Tuskegee Airmen achieving ace status, actually documented training in the “Double Vee.” Others have also remembered flying and training in the T-6.

“They’ve been terrific!” Cowell said. “They’re thrilled that I have this airplane for them. I feel honored to be history’s caretaker of this plane. What’s serendipitous about this plane, myself and the Tuskegee Airmen is that we all never gave up when faced with obstacles keeping us from flying. They persevered and I persevered to preserve this plane for history and honor the men that flew it.”

The Tuskegee Airmen boasted the only fighter group ever to not lose a single bomber while under escort and the only fighter squadron to sink an Axis destroyer with just the guns from two P-47s. That, along with a myriad of other accomplishments both in combat and away from combat, is what makes the Tuskegee Airmen’s legacy so unique.

Currently, Cowell is gaining the respect of the aviation community through his dedication to the aircraft. When he displays his T-6 at air shows across the country, it’s accompanied by a display that’s “second to none” museum quality.

“It really tells the complete story,” he says.

“I couldn’t do this all by myself,” he says. “What has really helped me do what I do, which is preserve history, carry on the legacy, and show what can happen if you keep your heart in your dreams, are the supporters and sponsors that stand by me. Without them, it would be a lot more difficult to bring the plane to the public at various air shows across the country.”

He’s been approached by other museums across the nation, but Cowell plans on getting the “Double Vee” into the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. or the Southern Museum of Flight in Alabama.

“It needs to be retired to a place where everyone can see it,” he said.

In the next five years, he sees himself working with corporate sponsors in order to bring the plane to one of the more notable museums in the country. After that, he says, he’ll have “a complete sense of accomplishment.”

“Right now I’m a little over three quarters,” he said. “But I’m getting there.”

For more information, visit [http://www.double-vee.com].