By S. Clayton Moore

Mike Mullane, the author of “Riding Rockets,” is looking forward to more physical challenges. “I want to take some time off and climb a few more mountains,” he said.

Space shuttle astronaut Mike Mullane has pulled back the curtains on NASA in his revealing new autobiography, “Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut.” His raw, touching and often laugh-out-loud book does for space flight what “North Dallas Forty” did for football. In “Riding Rockets,” the three-time mission specialist and decorated combat veteran tells stories that once could’ve been heard only in the hallowed halls of the Johnson Space Center, or if you were lucky, over a few beers at the Astronaut Beach House, a small retreat a few miles from the Kennedy Space Center.

Mullane describes in exhilarating detail the most important moments of his adventurous life, from his rocket-strewn childhood in the deserts of New Mexico to the immense joy of his first escape into orbit. Yet his book isn’t for the weak of heart. Mullane has written several acclaimed books for youngsters, but his autobiography is a decidedly adult tale, full of flyboy hell-raising and the occasional dirty joke. His language is blunt when he talks about the bountiful and unrefined humor that emerges in the competitive fishbowl of the military and the space program.

In a tale that Apollo 7 astronaut Walter Cunningham calls “brutally honest,” Mullane pulls no punches. He admits to fierce arguments with NASA administrators and his own “arrested development” as a cocky military aviator, initially treating his fellow civilian astronauts with wary suspicion.

“It’s a bit more honest than some of the books written by astronauts,” Mullane admitted. “Most people think that all astronaut books are children’s books and that we’re all Boy Scouts. I just tell the good, the bad and the ugly, just as it happened. It’s how I lived it.”

“Riding Rockets” also offers a unique perspective on mission STS 51-L, the Challenger disaster that claimed the lives of seven astronauts, including many of Mullane’s friends. The book is being released on January 24 to mark the 20th anniversary of the tragedy.

“The Challenger tragedy was a real watershed moment in my life, because of my friends who were killed and the effect that it had on the country,” Mullane said.

The rocketeer

Mike Mullane was born on Sept. 10, 1945, in Wichita Falls, Texas, but considers Albuquerque, N.M. his true hometown. From a very early age, he says seismic forces were at work. He was an impressionable 10 year old when his father was diagnosed with polio, leaving him in a wheelchair.

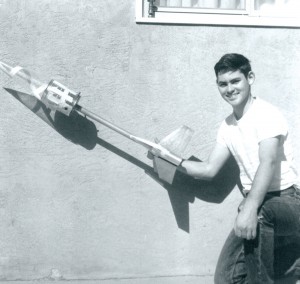

Mike Mullane became fascinated with rockets as a child. He used household items to build them from scratch.

“My mom and dad’s response was important to our family,” Mullane said. “I see now that their example really paid dividends in my life, because I inherited that sense of tenacity. I really needed that toughness because I wasn’t a born genius, as a lot of astronauts are. I’m the Forrest Gump of astronauts. I needed that lesson.”

Despite his father’s illness, the family traveled extensively. Those adventures gave the young astronaut-to-be his tremendous sense of curiosity.

“They dragged us around all over the West, imparting to us the sense of wonder at looking up at God’s creations,” he remembered. “My parents were fiercely exploratory. They loved going out in the wilderness and driving on roads few other people would attempt. It certainly always made me wonder what’s around the next bend.”

Another fundamental event happened in 1957, when the Russians launched Sputnik into space. Between that first satellite and movies like “When Worlds Collide,” he was gripped by the idea of space travel.

Some of his experiments didn’t work out so well. He made a parachute by holding a sheet over his head and jumping off his grandmother’s porch, breaking his leg. But he recovered and launched himself into making homebuilt rockets, a memory that makes the retired astronaut laugh out loud.

“Because I flew combat in Vietnam and flew on the space shuttle, most people assume that I faced incredible danger in my life,” Mullane said. “In reality, the most dangerous period in any male’s life is when he’s a teenager, because teenage boys don’t have a brain in their head! Those pictures of me screwing around with those rockets and having them blow up are certainly proof of that.”

He says that Catholic education at St. Pius X Catholic High School may have stunted his emotional growth, but it also aided his personal focus.

“One thing a Catholic education was good for was making sure you knew that your life was your life, and you’re responsible for it,” he said. “Whatever happens is a direct result of your actions, and you can’t pawn it off on outside forces. It taught me a lot of responsibility.”

Hills and valleys

Mike Mullane served as a weapons systems operator in F-4 Phantoms during the air war in Vietnam, flying 134 combat missions.

Mullane graduated from high school in 1963, and went on to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point.

“Meeting the demands of the education process was another thing that helped me because I wasn’t a naturally gifted person,” Mullane said. “I wasn’t the smartest or the best looking or the most popular guy. It was that focus on my goals that got me through.”

On Jan. 3, 1965, another momentous event occurred. Mullane was introduced to his future wife, Donna, at a party at her cousin’s home. They were quickly engaged, and married in 1966.

“I married probably the only woman I could’ve married who would stick with me through an immature young adult life,” Mullane said. “My wife’s support allowed me the focus to get through the various schools I had to get through in order to be competitive, and the training that got me through combat. It wasn’t easy for her, and she paid a big price for it. If she hadn’t stepped into that party and kissed me, I wouldn’t be an astronaut. I know that for sure.”

Mullane went straight into the Air Force following his graduation. Deficient eyesight kept him from becoming a pilot but he quickly qualified as a weapons systems operator, the proverbial “guy in back,” on RF-4C Phantoms. He flew 134 combat missions in Vietnam from January to November of 1969.

“I certainly got the dickens scared out of me,” Mullane remembered. “We did a lot of night flying at low altitudes with very primitive terrain-following radar. It’s just ink black in front of you, and you know there are mountains looming up ahead. That frightened me as much as the occasional tracers. If that radar wasn’t aligned properly, I would’ve been a grease spot on the side of a hill.”

He subsequently served a four-year tour in England and earned a master’s in aeronautical engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology. He was serving as a flight test weapons systems operator at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida when he got the most important call of his life.

The TFNGs

Following an intense interview and application process, Mike Mullane became a member of the first shuttle-era class of astronauts in 1978. He got the call from George Abbey, chief of Flight Crew Operations Directorate, who asked if he would be interested in coming to Johnson Space Center.

“I was on top of the world, gloriously happy that I was selected,” Mullane recalled. “I met hundreds of fliers who were more qualified than I was, and more qualified than some of these legendary astronauts. Why I got selected and other people didn’t, I can’t answer. That’s where you get into a spiritual answer.”

Mullane’s class of astronauts was quickly dubbed the TFNGs, an acronym with roots in an unprintable military phrase that was scrubbed down for the press to “Thirty-Five New Guys.” Their class t-shirt from 1978 read, “We Deliver.”

The extraordinary group of people included Sally Ride, the first American woman in space; Guy Bluford, the first African-American in space; and El Onizuka, the first Asian-American in space. It also included military hotshots from Mullane’s world, such as Robert “Hoot” Gibson and Michael Coats, who was recently appointed the new director of Johnson Space Center. Altogether, the TFNGs logged nearly 1,000 days in space and 16 spacewalks.

“There’s no doubt that a lot of history was written by the TFNGs,” Mullane said. “There were a lot of firsts, and we did some incredible things.”

First came the intensive training required of every astronaut, from zipping over Texas in T-38 Talons to rides on the “Vomit Comet,” a modified KC-135A, which induced short periods of weightlessness as well as nausea.

“The most physically challenging aspect of training for space flight is preparing for space walks,” Mullane observed. “It’s the most physically demanding thing to get in a 300-pound pressurized spacesuit, lowered under water. Everybody thinks you’re weightless under water, but you’re not. You fall right into the neck of the suit.”

Mullane also had to endure the quiet agony of waiting to be assigned to a shuttle flight.

“As far as the overall astronaut experience, I have to say that the training is a lot of fun,” he said. “You get to practice in the simulators and fly the T-38s. That’s hardly work. The thing that was most frustrating was the lengthy delays. When you think about it, I was there for 12 years and I flew a total of two weeks in space. That’s a typical experience. It’s all that time waiting to fly and the uncertainty of whether you’re going to fly at all.”

Prime crew

His first assignment to prime crew came in 1983, when Abbey offered Mullane a spot as a mission specialist on STS-41D, the maiden voyage of Discovery.

The “Zoo Crew” included one of the first space-bound women, Judy Resnik, who provided some of Mullane’s first lessons in working with women. As the product of the all-male environments of Catholic school, West Point and the military, Mullane admits he was suffering from an “arrested development,” especially when it came to women. At first, he was very distrustful of the civilian astronauts in general and was unconvinced they had the passion or skills of the military astronaut trainees. He was also suspicious of women astronauts like Sally Ride, who made her feminist politics apparent. But as Mullane began spending hours in the simulators with Resnik, Ride and Rhea Seddon, he began to come around.

“Remember my transition,” he said. “I walked into NASA as this cocky military guy, secure in my own abilities, and I saw these civilians as interlopers. I slowly came to appreciate that these guys were as good as me, and in some cases, better than me. Just being a military combat veteran doesn’t make you the best astronaut.”

Resnik, who was killed in the Challenger disaster, could give as good as she got when it came to Mullane’s antics. After hearing about a comical meeting between Mullane and sultry movie star Bo Derek, who was filming “Tarzan, the Ape Man,” she permanently saddled him with the nickname “Tarzan.”

“Judy Resnik, Rhea Seddon and the other women at NASA really opened my eyes,” he admitted. “They had dreams and ambitions and were just as good as any male astronaut. Judy was certainly an example of a woman who was very competent. I trusted her with my life and would do it again if she were here.”

Discovery’s maiden voyage couldn’t even get off the ground at first. STS-41D’s first attempt at launch suffered an engine start abort just seconds before liftoff. The misfire frustrated NASA’s astronauts and engineers and gave Mullane an early taste of the immense fear that a shuttle launch can inspire.

“I was more frightened on the shuttle than in combat by a long shot,” he said. “You have these hours and hours of anticipatory fear sitting out on the pad, which you don’t have in combat.”

Literally millions of things can go wrong when you’re sitting on top of 3.8 million pounds of fuel, in a vehicle with no escape system. There’s also the little publicized fact that every space shuttle is equipped with a flight termination system. The FTS is basically a string of dynamite along each solid rocket booster and the external fuel tank. Its job is to blow up the shuttle in case something goes terribly wrong.

“Most people are oblivious to that fact,” Mullane said. “Think of the incongruity of the situation. You’ve built a rocket with no escape system, because nothing can go wrong, yet they put dynamite on it to blow it up in case something goes wrong.”

A few days later, Discovery was successfully launched. On Aug. 30, 1984, at 50 miles above the earth, Mike Mullane earned his gold astronaut pin.

“There were still a thousand things that could kill me, but their threat couldn’t tug me away from the moment,” he wrote in his book. “I stared into the black and watched images of my childhood play in my mind’s eye. … I saw myself lying in the desert watching Sputnik and Echo streak across the night sky. I had achieved the dream of ten thousand nights. I was an astronaut.”

The crew of STS-41D deployed three satellites, extended a 102-foot solar wing and conducted several experiments. They filmed their experiences with the newly developed IMAX camera.

Mullane’s descriptions of space are poetic.

“Every 90 minutes, I would watch the incomparable beauty of an orbit sunrise,” he writes. “I would watch as a thin indigo arc would grow to separate the black of nighttime earth from the black of space. Quickly, concentric arcs of purple and blue would rise to push the black higher and higher. Then bands of orange and red would blossom from the horizon to complete the spectacle.”

Looking back on photographs during his research, Mullane found them wanting in comparison to his rich memories.

“It’s impossible to capture the beauty of space,” he said. “This vastness of ocean and sky and blackness and all the colors of the sunrise can’t be captured. I never got tired of looking out that window. People ask me if there’s television on the space shuttle and I just have to laugh. You stick your nose in the window and enjoy every minute of it.”

Challenger

Part of the reason Mullane wanted to tell his story was to show people the sheer bravery, not just of his fellow astronauts, but also of their families.

“I would like to think that this book is going to open eyes as to what we endure as astronauts and what our families endure,” Mullane said.

One of the worst duties for Mullane and his fellow astronauts was escorting families to watch the launches from the roof of the Kennedy Space Center.

“Having been on that roof one time as that escort into widowhood, I’d rather be on top of that rocket,” Mullane said. “It’s a terror of the first magnitude for those spouses to watch those launches.”

His worst fears came true on Jan. 28, 1986, when Challenger exploded, killing all seven astronauts aboard.

When he began writing, Mullane initially planned to write specifically about Challenger, but was convinced to tell his own complete life story. His descriptions of what the crew went through are chilling, but he felt that the truth needed to be told.

“I was reluctant to emphasize that we had a fortress cockpit,” Mullane explained. “We definitely know the Challenger crew survived the breakup and was throwing switches. We can hope that there was a rapid enough decompression that after they threw a couple of switches they fell unconscious, but there’s no guarantee. I thought about it a lot, and I think it’s important for people to understand. Hopefully, whoever designs the next rocket understands that we need escape systems.”

Mullane believes that NASA’s successes up to that point made possible the failures that caused the losses of Challenger and Columbia.

“When you’ve put people on the moon and brought them back safely, you have to be feeling good about yourself,” Mullane explained. “I’m sure if those engineers were here right now, they’d be talking about mean times between failures and redundancies. You get lost in the numbers. Those are all indications of post-Apollo hubris.”

The astronauts began to push back against an administration that had corralled much of the astronaut office through fear.

“There was always this fear that you could say something and it would jeopardize your career,” Mullane remembered. “You need strong, fair leaders to stand up and say they don’t have a patent on being right.”

Despite butting heads with administrators, Mullane was assigned to two further shuttle flights, STS-27 in 1988 and STS-36 in 1990, both on Atlantis. Those flights carried Department of Defense payloads and remain largely classified.

“Challenger broke everybody’s hearts, but we were all anxious to fly again,” Mullane said. “There’s no doubt that Challenger weighed on our minds, but I wasn’t any more frightened on my second or third mission, post-Challenger, than I was on my first mission. I was terrified on all of them.”

He thought about Judy Resnik as he prepared to board his last ride into space.

“I could see Judy’s smile, her wind-whipped hair,” he wrote. “I could hear her voice, ‘See you in space, Tarzan.’ I missed her. I missed them all.”

Lessons learned

After 12 years as an astronaut and three flights into space, Mike Mullane decided to retire in 1990.

“There were a lot of factors involved in my decision to retire,” Mullane observed. “I had these frustrations with management. I could have a health problem that could ground me. Frankly, my fear and Donna’s fear had a lot to do with it. It was killing my wife and my mother. It was killing me, too, although if someone had told me right after my decision to retire that if I changed my mind, I was on the next flight, I would have been going.”

It’s difficult for any astronaut to give up their lofty perch, in many ways.

“I think it weighs on every astronaut,” Mullane said. “You never want to give up that title. When you’re hypercompetitive, you’re always looking for that rung on the ladder above. Then you go into space, and there’s no rung above you. You have to climb down to meet the next challenge. What do you do for an encore?”

Although he has been blunt in his criticism of NASA’s failures, he sees signs of hope.

“Columbia is a terrible indictment of NASA because it’s basically a repeat of Challenger, where schedule became more important than safety,” he said. “I don’t see that problem now. I think the agency finally got it. You can’t continue to fly a vehicle like the shuttle, which is so expensive and so dangerous. We need to go on to the next great thing if we intend to go back to the moon and on to Mars.”

In his post-NASA career, Mullane has worn many hats. He tried his hand at writing fiction with a thriller entitled “Red Sky,” and wrote two award-winning children’s books, “Liftoff!” and “Do Your Ears Pop in Space?” He also stumbled into a career as a public speaker, which keeps him on the road.

“I got a strong lesson in how important empowerment was from Challenger,” he explained. “In the Air Force, I flew with a general one time, and right before we took off, he said, ‘There’s no rank in this cockpit. If you see something, say something. You’re not just a passenger here. You’re somebody who’s going to help keep us alive.'”

Now Mullane has focused his ideas into several robust programs about leadership, which have helped organizations all over the country.

“Over the years, I put more of a message into the talk. It evolved into a powerful lesson about teamwork,” Mullane said. “There’s a lot of humor in it. I draw on my experience in the Air Force and NASA, as well as the Challenger and Columbia disasters, to make some points about leadership.”

The last TFNG reunion was in 1998. At that time, the surviving class members were presented with updated t-shirts that read, “We Delivered.”

With “Riding Rockets,” Mullane also describes the lighter side of the astronaut experience, from the surreal physical tests to hijinks and pranks pulled everywhere from the Astronaut Beach House to the shuttle itself.

“Oh, there are stories I didn’t print,” Mullane laughed. “I didn’t want to embarrass anybody but myself. But I’ve always enjoyed laughing and making people laugh. If I have the opportunity to tell a story, I enjoy it. I just started telling these stories, and some of them even made me laugh when I recalled them.”

The book has garnered enormous praise from fellow astronauts Michael Coats, Rhea Seddon and Hoot Gibson. Space-oriented authors like Homer Hickam (“Rocket Boys”) and Walter Boyne (“The Wild Blue”) have given their stamp of approval. Even legends like Apollo 13 Commander Jim Lovell have praised “Riding Rockets.” General Chuck Yeager said, “It’s a pleasure to read Mike Mullane’s entertaining depiction of the NASA astronaut corps. He tells it like it is, and not the way NASA’s painted it for so many years.”

It’s quite a story, and Mullane has absolutely no regrets about any of it.

“Personally, I’ve had a dream come true,” he said. “I’ve learned a lot. I feel like I was blessed with the right help and the right people around me. I feel fulfilled by that, and I will always have that overwhelming sense of accomplishment.”

“Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut,” published by Scribner, will be released on January 24. For more information about Mike Mullane and his speaking programs, visit [http://www.mikemullane.com].

- Early in his career, Mike Mullane and fellow astronaut Steve Hawley ran into movie star Bo Derek. The event caused Judy Resnik to forever saddle him with the nickname “Tarzan.” L to R: Mike Mullane, Bo Derek and Steve Hawley.

- Mike Mullane experiences the joy of weightlessness during the maiden flight of Discovery.

- In “Riding Rockets,” Mike Mullane recounts the joy of space flight and the heartbreak of the Challenger disaster.

- Mike Mullane (center) has enjoyed some of the world’s only weightless baseball and football games.

- Mike Mullane (far left) and the crew of the maiden flight of Discovery.