By Karen Di Piazza

Bing Lantis, president and CEO of The Lancair Company, loves flying “Big Bird,” the Columbia 400, which was recently certified by the FAA.

Founded in February 1995, The Lancair Company began manufacturing the Columbia line of all-composite, high-performance certified aircraft. Based in Bend, Ore., the company is currently delivering the all-electric, Columbia 350 and its newly FAA-certified Columbia 400, which Bing Lantis, the company’s president and CEO refers to as “turbocharged, piston-fast!”

This sounds great so far, but TLC has seen some dark days—actually, about 365 of them. Just when things seemed promising, America was under attack during the 9/11 events, and those events weakened the economy further, forcing the embryonic aviation manufacturer to put the C400 project on hold. In fact, they shut their doors for a short period.

Lantis said that convincing American financial institutions to invest millions of dollars into a start-up aviation company before 9/11 was questionable at best; after the attacks, it wasn’t a possibility.

Lantis said that executives used to go out and play golf, not so much for the sport, but because it was the “good ol’ boy way of clenching the business deal.”

“That worked 30 years ago, but only if you didn’t beat your opponent,” he laughed. “My four golf memberships haven’t been used in years. Locking down funding from American investors on the green isn’t how it’s done anymore, not for a risky aviation company! The American Dream—it’s the Malaysian government! Malaysia is TLC’s business partner.”

Lantis says that today, becoming successful is a matter of who can get foreign investment money the quickest.

“Cirrus Design beat us in the race for foreign funding when Crescent Capital, a foreign banking entity, invested millions into the Cirrus aircraft,” he said. “I don’t think people understand how difficult it is to attract American investors. The idea itself is a dying breed; that’s not where the money is.

“Recently, the government of Malaysia has invested more money into the company, which we needed in order to continue rolling out our all-composite, four-seat single-engine C350s and C400s. The FAA recently certified our C400, but it took a long time; we didn’t know two years ago when and if we’d be able to go forward.”

Lantis said if it had not been for the Malaysian government, they might not have survived.

“Lance Neibauer, the founder of our company and our chief design officer, is now one of seven board members,” Lantis said. “He deserves the credit for setting the wheels in motion with Malaysia. Over 20 years ago, Lance began building the Lancair family of kit-built planes, but later, he started TLC with its FAA-certified aircraft.”

Lantis joined the company about four years ago, shortly after that relationship began. He said with more investment money from the Malaysian government, TLC is expanding its facilities, adding a 40,000-square-foot building, inclusive of new composite ovens.

Lantis recalls an event two years ago at the LIMA Airshow that could’ve put a halt to further good relationships with the Malaysian government, if things had turned out differently. After a C300 demonstrator was purchased for TLC’s sales and service center in that country, Malaysian Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad decided he should fly it.

“One of our chief pilots went with him,” Lantis recalled. “Myself, Lance, and Mohamad’s bodyguards waved him off for what was supposed to be a 10-minutue ceremonial flight. After the 10-minute mark, there was no sign of the plane.”

Thirty minutes later, there was still no sign of him, and they were getting worried.

“His bodyguards were becoming frantic,” Lantis said. “An hour has gone by. We all said, ‘Oh this can’t be happening.’ The countryside is vast there. Long after the 60-minute mark, here he comes, taxing down the airfield with a big grin on his face. In a calm tone he said, ‘The flight was so pleasurable, I thought I’d just admire the beautiful countryside!'”

Taking care of business

Lantis, a pilot and 35-year industry veteran, knows how to shipshape companies. From 1995 to 1997, he was president and CEO of the Mooney Aircraft Company. Two years before joining The Lancair Company, he was its business consultant. He knew exactly what they needed. Neibauer said that he and the company’s investors wanted and needed an aggressive “can-do” leader.

“We needed someone who could bring the company out of the red and into the black, and keep our philosophy of producing the best single-engine aircraft at the forefront,” Neibauer said.

Lantis was their man. He had already proven himself; it was a logical choice hiring him as the company’s president. Later, he became CEO.

“The Lancair Company was way behind the curve from Cirrus,” he said. “We actually got our type certificate for the original Columbia 300 just two weeks before Cirrus got theirs. We were sort of on a parallel path with them. Cirrus was fortunate that they received funding from a foreign investment bank when they did. I think in about March of 2001, we began the process to get an investment bank.”

Lantis became president in June, and they signed up an investment bank on Sept. 6, 2001.

“Talk about timing, but our timing wasn’t as good,” he said. “I know I sound very competitive about Cirrus, and I am. We’re aggressively catching up in the market.”

It’s Lantis’ belief that if TLC would have received funding at the same time that Cirrus did, they’d be ahead of them. It would be them, not Cirrus, who put Textron-owned Cessna in the number two slot as the second largest maker of piston-powered aircraft in 2004.

Nevertheless, TLC sold over 160 aircraft in 2004. Ironically, Lantis owned a Cessna 414, but after both his wife and father developed medical problems, which made it difficult flying in smaller aircraft, he sold it.

“If they fly, it has to be in commercial airliners; too bad, because I’d love to fly them in a C400!” he said. “It’s an amazingly fast plane. I fly ‘Big Bird,’ our yellow-painted demo C400, from time to time.”

As much fun as it may be flying the C400 and the C350, which is an upgraded version of the C300, the company’s first certified aircraft in 1998, the focus for 2005 is producing more aircraft.

“With additional funding, we’ll ramp production rates up to 200 aircraft this year, producing both models,” Lantis said. “The C400 is roughly priced at $525,000, equipped with everything. The C350 sells for about $400,000, depending upon upgrades. We just got certification for air-conditioning last month, so we’ve started installations on that as well.”

The Columbia line of aircraft has state-of-the-art instrument and navigational avionics. The C400’s panel comes with an Avidyne FlightMax Entegra system, a two-screen unit that features the EXP5000 primary flight display with an integrated, solid-state air data and attitude and reference. It also has an EX5000 multi-function display, a superb navigational and awareness systems instrumentation. The MFD virtually has a voice of its own; all parameters of the aircraft’s systems, including the engine performance and percentage power usage, are right there in front of the pilot’s eyes. It sure beats those six-inch, round knobs!

Aircraft such as this, with advanced avionics’ technology, is helping to reduce accidents, especially with TLC’s Ryan 9900BX Traffic Avoidance System, known in the industry as TAS and XM Weather. DataLink, a weather avionic detector that has been available on the company’s aircraft for a couple years, has added the XM weather to the aircraft’s avionics suite because it’s safer.

Both the C350 and C400 have Continental engines and dual turbochargers. The pilot’s operating handbook describes the C400 zooming 235 knots across the sky, based on 25 gallons per hour.

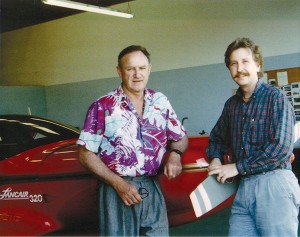

Actor Gene Hackman and Lance A. Neibauer, founder of The Lancair Company, have some laughs together.

“We will be initiating a production rate increase to one aircraft per day by late summer, with interim rate increases the first half of 2005,” Lantis said. “But we won’t announce any new innovations or models until they are fully certified and ‘in production.’ But it’s a safe bet to say that TLC will be making some noise in 2005.”

But Lantis did relent and spill the beans, telling Airport Journals that TLC will fund its own marketing program.

“We’re going to advertise, which we really haven’t done; for us that’s a lot of noise,” he laughed. “Additionally, we’re adding to our sales force, offering new sales tools with more options. We’re going to have a new website, too.”

Lantis explained that having a new website is important for the company’s identity.

“Our current website is confusing people,” he said. “We’re The Lancair Company, a manufacturer of FAA-certified aircraft, not kit-built planes, but because Lance owns the licensing rights to the name of our company, and as well, Lancair International, a kit-built company, the website homepage is split literally in half with both of us. We have absolutely nothing to do with the kit aircraft and we don’t plan to. In fact, Lance just sold his kit company to one of his customers.”

When asked if a name change was imminent, Lantis said he wasn’t at liberty to discuss it.

One thing that definitely will not change, according to Lantis, is the company’s three-day, intense factory training program.

“We don’t care how much experience a pilot has; they aren’t flying off anywhere without completing our factory training,” he said. “In the last five-year period, we haven’t had one fatal accident and we want to keep it that way.”

That’s reassuring, but just in case, the company’s aircraft has a new three-point harness design, which decreases load pressure on the shoulders, should there be a crash. This feature decreases load by 12 percent, which is based on a four-point system.

The aircraft, designed with “what ifs” in mind, has redundant flight-control hinges that do the job of eliminating single-point failures. And just as important, the cabin’s emergency door releases automatically, if the plane ends up resting in an inverted position, such as in a tree, for instance. Roll cages are popular safety devices as well; TLC’s cabin has a three-G rating.

“Other than us and Cirrus, no one else has had aircraft certified under FAR Part 23, which in our case, means that it’s ‘spin-resistant’ aircraft,” Lantis said. “We don’t have a parachute like Cirrus’ aircraft does. Nevertheless, our aircraft is sophisticated and training is very important.”

Training includes a full day of ground school on the avionics, a full day of ground school on the airplane and at least one full day of flight in the aircraft.

“After that, we either sign off the pilot, if he or she is an experienced pilot, IFR rated and all that, which is usually not an issue,” he said. “For the less experienced pilots, they may need additional time until our CFI signs them off.”

Lantis said there is no FAA-minimum flight-hour requirement that would prevent anyone from flying the aircraft—all the more reason for training.

“We’ve had a pilot here with 150 hours that was able to be signed off—of course, after he passed our factory training,” he said. “What we’ve seen for the average pilot hours is about 600 hours. A typical owner is an airline pilot. In some instances, our aircraft is more sophisticated than what they fly on the job. I would say about seven to 10 percent of our customers are ATPs; 75 percent of the pilots are instrument rated.”

Lantis said primarily business professionals fly C350s and C400s.

“Our aircraft are cross-country machines—not something you park in a hangar,” he said.

Lance Neibauer’s VLJ and design methodologies

There has been talk about a very light jet, but Lantis makes it clear; there has been no “official” announcement that TLC will produce one. On the other hand, Lance A. Neibauer is currently in the design phase of a six-seat, single-engine jet!

“As far as very light jets go, particularly the four-seat jets that are coming out, I think those are strictly an owner-flown airplane,” Lantis said. “There’s an owner-flown market, a professionally flown market and a market where the owner isn’t necessarily the pilot, like that of a PC12. Then there’s a transition market in between those segments. The market that used to buy Cessna’s 340 is still there; that market niche hasn’t been filled yet.”

He said the real question is whether it would make sense to go after a turboprop version of that market.

“I personally think there’s a market there,” he said. “As far as Lance designing a VLJ, I really can’t comment on that; he’s always designing something! Lance started his kit-designed planes in the seventies, out of his Southern California garage, and he’s won numerous design awards, which is evident in the look of our certified aircraft today. That’s really something—starting a business in your garage and taking it all the way to a manufacturing plant in Oregon.”

Neibauer, an IFR, multiengine-rated pilot who also enjoys flying his Italian-made helicopter, confirmed that he’s designing a VLJ for certification that will reach maximum FL290.

“It will be a lot faster than my 980 turbo plane, which I think went out of production in the mid-eighties,” Neibauer laughed, and then revealed something else he’s kept from the media until now. “Seriously, my design for a VLJ will be used for the corporate Part 91 segment.”

The 50-year-old visionary isn’t an aerospace engineer. Neibauer is quick to credit his team of engineers and aerodynamicists who help him work out airfoil designs and other structural relationships that make his visual ideas take flight.

“This aviation thing is in my blood,” he said. “I’m the nephew of Al Meyers, who founded the Meyers Aircraft Company in the late thirties. He died in 1976, but we still have Meyers Airport in Michigan, which is a privately owned airport designed for public use.”

Neibauer began his career as a graphic designer in 1971, after he received a bachelor of fine art’s degree from Michigan State University. The New York Museum of Modern Art, too, noticed his sleek airplane designs.

“Somehow, they managed to suspend my 320, a kit-built, two-seater, in midair. There it was, hanging from the museum’s ceiling in the main lobby,” he laughed.

Neibauer also owns Aviation Composites Technology, a Philippine-based company that manufactures parts for the Lancair IV PropJet turboprop, one of his earlier designs.

“The Mexican navy has purchased nine Lancair-made planes; four of them are the PropJet,” he said. “My kit-designed 320 became a certified plane in the Philippines; to date, it’s the only Philippine aircraft certification.”

One of the reasons Lantis couldn’t really comment on Neibauer’s VLJ design is because there are so many versions of it.

“I’ve done a lot of basic configuration design; it used to be on a drawing board, now it’s on a computer,” Neibauer said. “I’ve got single-engine jets, twin-engine jets, large ones and smaller ones. Currently, I would go with one of the single-engine jets, a six-seater, which is different from Diamond’s D-Jet. Theirs is a little bit smaller. My design has a bit more cabin space; it would be a relatively small six-seat jet, but it would give me the option of having a bathroom in it. I think having one is important; when you get up high, you don’t want to have to land because someone has to go!”

Lance Neibauer parks his Italian-made helicopter on his 25-acre ranch, which is where he spends most of his idle time.

He’s adamant, too, that his jet will fly to maximum FL290, because he says “it’s the smartest way to go.”

“There’s no reason not to, because there’s no real difference to speak of between FL250 and FL290, from an overall growth perspective,” he said.

He also said he didn’t think that Diamond and other VLJ OEMS have thought about flight levels enough.

“I’ve been manufacturing kit planes, which reach FL250, but that’s only because the kit planes have piston-powered engines,” he said. “Pistons really don’t like to go much higher. Turbine-powered aircraft isn’t a flight-level problem. Ideally, you’d go way up, but then you do have issues with the GA pilots’ training regime; things happen fast at 40,000 feet.”

He said that turbofan jets perform better at FL290.

“If you’re familiar with our new ‘reduced vertical separation minimum,’ which is currently above FL290, it’s the same as below,” he said. “You’ve got a thousand-foot separation in directions. In other words, with RVSM, an eastbound jet versus a westbound jet both will have to be separated by 1,000 feet. Odd numbers are eastbound and even numbers are westbound; it’s ATC’s job to monitor the airspace.”

He said he’s not convinced everyone understands RVSM.

“RVSM requirements mean that between the airspace of 29,000 feet and 39,000 feet, there’s now a 1,000-foot separation,” he said. “However, when you get to 40,000 feet, there’s actually no requirement. In that case, ATC assigns an altitude, making sure you stay at least 2,000 feet apart from oncoming traffic. Knowing this, that’s why I’m saying these OEMs haven’t thought this all the way through, and that’s why my VLJ will reach FL290.”

He’s also sure his VLJ will be composite—most of it, anyway.

“I like high-performance airplanes, so it’ll be a high-performance machine, and that means it will be mostly composite,” he said. “I don’t see the reason for not using composite for all the basic structures. Some things are easier to make out of aluminum, and sometimes metal is actually lighter, but for the main structure, it needs good composite technology.”

Neibauer believes that corporate Part 91 departments would use a six to eight-seat VLJ, if the cost is right and if it’s efficient. He absolutely doesn’t believe that the two-, four-, five- and six-seat VLJs will be used for commercial “glorified” air taxis.

“The air-taxi concept is a cockamamie notion,” he said. “The American public isn’t sitting around waiting anxiously for this; it’s a trade thing. The public doesn’t know about air taxis; they don’t care about it and they won’t do it! It’s not necessary for them to fly around in tiny jets.

“This is a dot-comer attitude; it’s an Eclipse/Vern Raburn idea. Raburn believes he’s going to dot-com change the world! He cannot make that business plan work, unless he sells hundreds and hundreds of jets each year. How can you do that? You have to come up with some cockamamie notion, and that’s it!”

When confronted with Eclipse’s claim that they have more than 2,156 orders for its Eclipse 500, a five-seat VLJ, Neibauer agreed with The Teal Group’s analyst Richard Aboulafia, who wants to see proof.

“It’s easy to put orders down; we had hundreds and hundreds of orders on our first Columbia 300, but if there’s no risk on the deposit, why not?” Neibauer said. “I know a guy that has an order on an Eclipse; he also has one on another VLJ, too. He doesn’t care; he has no risk. His deposits are in escrow accounts. So, I have no intention of coming up with hype that says my VLJ is the next air-taxi solution.”

He said the VLJ he’s designing is a couple of years away from flying, and by then, there would be more choices of power plants. He also said no one should rule out Honda as that supplier.

“It really takes about a two-year period before you can get a plane flying,” he said. “Usually, you start with wind-tunnel testing, so we have a lot of work ahead of us. With a project that big, you don’t want to miss anything.”

He said that at “board level,” he’s had private conversations with the government of Malaysia about funding his VLJ project.

“Right now, we just got the C400 off the ground, so our focus has been there,” he said. “Producing aircraft at a higher rate is the focus; getting production levels up will aid in other aircraft that we certify.”

Famous, funny and the awards

Over the years, well-known people have been interested in TLC aircraft. Neibauer recalls several events that involved purchases, or in some cases, “almost” purchases, which he says has left an impression on him of how to handle “off-the-wall” offers.

“After I landed on the ramp at Jackson Hole one day, tired and not really paying attention to the people around me, Harrison Ford walked up and asked me if I would build him a kit Lancair IV-P,” he said. “I explained that it was a long process. He’d have to put in or someone on his behalf would have to put in hours completing it, because it was a kit; the FAA has rules on kits, etc. He listened intently, using hand gestures, and he kept steady eye contact with me, but finally he asked, ‘Would you just sell me the one you flew in here with?’ Stupid me; I jokingly said no, I wouldn’t have a way home! Of course, if I had been thinking, and hadn’t been so tired, I would have sold him my plane and found other transportation home!”

Gene Hackman, who was fascinated with aviation, became friends with Neibauer years ago.

“He came over to my Santa Paula facility, and took a demo flight in the 320,” he said. “Then he became interested in my new prototype, the Lancair IV, which I worked on in 1990. He was seriously considering buying one, but after he took his flight physical, he was told by the doctor he had to give up flying.”

Burt Reynolds bought a 320 kit years ago, but Neibauer isn’t sure if he kept it or gave it to his ranch supervisor in Florida as a gift. And Larry Ellison, founder and CEO of software giant Oracle, who has been known to fly airplanes under bridges in San Francisco, purchased a completed 320 kit-built plane for his son.

“Ellison’s aircraft stories are a book in themselves,” laughed Neibauer. “I know he and his son went flying together in the 320 and they kept the plane for a couple of years. However, I don’t know if his son is an ‘alleged’ risk taker.”

One of Neibauer’s closet friends, Alexander Zuyev, the Russian pilot who defected to Turkey with a MiG-29, bought a Lancair IV-P.

“Sadly, he was killed in an unrelated flying accident in a Yak a couple of years ago,” he said. “He was a nice person. It was a real loss.”

Recently, Lord Robin Rotherwick, of the House of Lords in the U.K., completed his three-day factory training.

“He had originally ordered a kit ES, but he had difficulty with the local licensing issues in the U.K., so he ultimately changed his order to a Columbia 300, which is the certified version of the ES,” he said. “But because it had been four years since he ordered his aircraft, he upgraded to the Columbia turbo 400, which he flew home, across the Atlantic this past summer.”

Neibauer said he’s met several interesting people because of aviation; one of his good friends is Erik Lindbergh.

“After Erik landed at the Berlin Air Show, we flew the Columbia together from Paris,” he said. “That was a blast; he’s a good pilot.”

Neibauer has been actively involved in the development, construction and sale of advanced-composite aircraft since 1981, including the following experimental aircraft: Lancair 200, Lancair 235, Lancair 320, Lancair 360-MK2, Lancair ES, Lancair Super-ES, Lancair IV, Lancair IV-P, Lancair IV PropJet and the Lancair Columbia line of certified aircraft.

“I started out 20 years ago with what became the Lancair airplane—kit planes; two-seat and four-seat, high-performance airplanes, and they still are,” Neibauer said. “The reason that I started the FAA-certification process in the first place was that in 1995, with some prodding from the FAA, they were trying to stimulate general aviation. I was asked to give it a whirl, so I couldn’t turn that down. That’s when we started another, completely separate company, which became The Lancair Company.”

The Lancair Company’s C400, an all composite, single-engine, piston-powered four-seater, is the pride of the company.

For his contributions to the betterment of aviation, and for his designs and engineering, he’s received several awards and citations, including the Experimental Aircraft Association’s Raspet Award for advancement of general aviation in America, presented in 1989. He was included in the list of Designer News’ Top Ten U.S. Designers/Engineers in 1991, and the Light Aircraft Manufacturers Association presented him the President’s Award in 1993. During that same year, he received Teledyne Continental Motors’ Achievement Award for significant contributions to general aviation.

In 1997, Entrepreneur Magazine listed him among their Top Ten Entrepreneurs and in 1998, the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association presented him with a special citation for “New Era of Aircraft with Improved Performance and Enhanced Safety.” That same year, he was listed among Aviation International’s Top Ten Aviation Newsmakers.

But his design acumen isn’t limited to aircraft.

“One day, I just started designing this house,” he said. “It ended up to be a 4,500-foot ranch home. The horses, cows and goats have a 25-acre play space. I use a lot of land running my hay business. The scenery isn’t bad around here, and I like being here and designing aircraft from inside my home when I have idle time.”

Neibauer said he’s been fortunate to have made a lot of money in his lifetime, and that he could afford to travel around the world, but he doesn’t plan on straying too far from his ranch.

“Really, I’m happy here,” he said. “In fact, I was just vaccinating cows the other day, so I’m kind of a cowboy. I have a bunch of hats, too.”

For more information, visit [http://www.lancair.com/].