By Karen Di Piazza

On the morning of June 4, 1964, the unthinkable happened; Learjet prototype 001 crashed and burned on takeoff, with a Federal Aviation Administration test pilot as pilot-in-command, and one of Lear’s pilots as second-in-command. Bill Lear, who never had much love for the FAA, turned this fiasco around to his advantage.

“Jeeb Halaby was FAA administrator at the time,” Bill Lear Jr. explained. “Dad really lit into him for sending such an incompetent FAA test pilot to fly his aircraft. Jeeb was justifiably embarrassed. The Old Man made the FAA responsible for the loss of his Learjet; he put the onus on them to get his airplane certified!”

With friends in high places, Bill Lear was quickly on the phone to Senator Barry Goldwater.

“The FAA pulled out all the stops after that phone call,” Lear Jr. laughed. “The Learjet Model 23 received its FAA certification on July 31, 1964—just seven weeks after the FAA crashed our first prototype, only 10 months after first flight and four months before our competitor, the Jet Commander, became certified.”

Stories have always circulated around Lear and his aircraft. For instance, it’s been reported that Lear Sr. imported a team of midgets from California to work inside the slender fuselages of the first Learjets built in Wichita, saying, “If it takes midgets, that’s what we’ll use.” Lear Jr. says that’s outrageously false.

“During WWII, I believe Lockheed used midgets, to crawl into small areas to buck rivets,” he said. “How it got from Lockheed to Learjets is pure fantasy. The Learjet fuselage isn’t slender; a six-footer can work inside of it! My father may have done what appeared by some to be peculiar things, but he never involved himself in any ‘crazy antics.'”

However, he said there are a lot of true, funny things his father did and said. During an NBAA convention, a potential client sat in the Learjet mockup and complained to Bill Lear that he couldn’t stand up.

“Dad replied, ‘You’re absolutely right, and you can’t stand up in your f—ing Rolls-Royce, so if you want to be able to stand up, walk around, and fly three times slower, then buy yourself a DC-3,'” he laughed. “With the conversation over, the dude ordered a Learjet!”

He said his father was a maverick because he was always years ahead of his time, and that one of many true statements he made was, “The FAA is nothing more than a carbuncle on the ass of progress and has set aviation back at least 20 years.”

“I’d go along with that,” Lear Jr. said.

Rags to riches

Bill Lear was posthumously inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1978, and was enshrined in the International Aerospace Hall of Fame three years later. His rags-to-riches story is even better than anything he read in Horatio Alger Jr.’s books as a teenager.

The self-made millionaire was famous long before the Learjet. He received aviation’s most distinguished award, the Collier Trophy, presented to him by President Truman in 1950, for his invention of the most compact autopilot in the world.

Patenting more than 150 designs and inventions in electronics and aerodynamics, he developed the eight-track stereo tape player, redesigned the way B batteries were used in car radios (with the Vibrator), and developed the first swept-back antenna, the first light-weight affordable radio compass and various attitude and directional gyro systems.

“I don’t care how much money or time it takes; I’ll attack it on the basis of ‘it can be’ done. I don’t think there has been a single thing I ever did, where I didn’t first recognize there was a need for it. Just thinking up something great out of nothing is an exercise in futility,” Lear said in 1967, in a videotaped autobiography, “By the Seat of His Pants” (provided by Bill Lear Jr.).

Lear formed dozens of companies, sometimes dangling on the brink of financial ruin.

“The Old Man pulled off miracles,” said Bill Lear Jr., former president of Learjet International, S.A, and chair and president of Lear Inc., after his father’s death.

Faithless to fearless

William Powell Lear, the only child of Reuben Marion and Gertrude Elizabeth (Powell) Lear, was born on June 26, 1902, in Hannibal, Mo. He endured a lonely, miserable and unstable childhood. After his mother and father separated when he was 6 years old, he lived in Chicago with his mother, who was both verbally and physically abusive to him, causing him to feel “faithless and worthless.”

“My father’s mother, Gertrude, was a Bible-thumping, tyrannical, child-beating, flaming redheaded bitch,” Bill Lear Jr. said frankly.

He said he understood why his father would later run away from home, particularly after he spent a horrid three-week summer vacation with his grandmother, when he was 8. He described the conditions as “appalling.” There wasn’t running water or electricity, and he recalls the stench from a slop-bucket the pigs ate from, which was kept on the floor next to the kitchen sink.

Bill Lear took refuge from his mother reading books about electricity. By age 12, he had built a radio set with earphones, mastered Morse code, and had pieced together a crude telegraph. He later said Horatio Alger books helped him go from faithless to fearless.

“It was always situations where the young man had no real reason to expect opportunities in life,” he said of what he read. “He always found opportunities by virtues of his willingness to ‘do and to dare.’ This was a physiological stimulus for someone in my position, as my mother was always trying to drill it into me that I would never be anything: Once a poor boy, always a poor boy.”

Reading Tom Swift adventure stories helped him decide to drop out of high school, after attending eighth grade for only eight weeks. He didn’t need school; he knew more about electronics than his teachers did.

He took odd jobs, mostly working with electronics, and at 18, he joined the Navy for six months and became a wireless instructor. After WWI, Lear learned how to fly; he applied his knowledge of electronics to aviation.

Business, marriages and children

From 1922 to 1924, Lear was president of Quincy Radio Laboratory in Quincy, Ill., and from 1924 to 1928, of Lear Radio Laboratory in Tulsa. He also founded the Radio Wire and Coil Co.

One of his customers was Paul Galvin, president of Galvin Manufacturing Co., which built radios. Galvin bought Lear’s coils and hired him as chief engineer. Another Galvin product was a B-battery eliminator that Lear designed and patented; it adapted battery-operated radios to household current. Lear also convinced Galvin to start designing and manufacturing car radios, and helped come up with Motorola for the radio name.

Shortly after that, Lear founded Lear Developments, which became Lear Inc., and later, Lear-Siegler Inc., with its core business in aerospace instruments and electronics.

“Dad became somewhat successful; we lived in a rented mansion,” said Bill Lear Jr.

The author of the autobiography, “Fly Fast, Sin Boldly; Flying, Spying & Surviving,” explained that his mother wasn’t Lear’s first wife. During the early 1920s, “Willy” Lear married Ethel Peterson. In 1925, he fell in love with 17-year-old Madeline Murphy.

“Dad was still married to his first wife,” Lear Jr. said.

Lear was arrested in 1926, when the FBI caught up with him in Buffalo, N.Y., for taking the under-aged Murphy across the state line; he was indicted with a felony violation of the Mann Act (trafficking in white slavery).

“But Dad and Mom married in October of that year,” Lear said. “The marriage nullified the government’s case.”

Bill Lear Jr., born May 24, 1928, wasn’t the first William P. Lear Jr.

“My half-brother, from Dad’s first marriage, died five and half months after birth in 1924, from a congenital heart defect,” he said. Thirteen months after the birth of the second Bill Lear Jr., Madeline Lear gave birth to a girl, Patti.

“According to Mom, Dad was absolutely livid,” Lear said. “He blamed her for getting pregnant.”

He said that moving into the rented mansion was a way to try to save his faltering marriage.

“Dad was trying to woo Mom back to the nest with all this display of wealth and grandeur,” he said. “He had been fooling around, and she knew it.”

By 1933, their marriage ended; a very sad 5-year-old Bill Lear Jr. didn’t understand why only he, his sister and mother would be “exiled to Miami” from Chicago, to live in a small, rented house. Madeline Lear never remarried.

Lear, who said his father wasn’t close to any of his kids, because “he was too much of a perfectionist,” rarely saw his father—yearly, if he was lucky. Courtesy of the Lear gene, he didn’t have much of an interest in anything except electronics. Meanwhile, back in Chicago, his father was running his electronics factory. He would receive penny postcards from his son telling him of his passion for electronics, but he was too busy to respond. He had no idea that his son was a “do or dare” guy, too, working two to three part-time jobs after school, so he could purchase parts to construct his own one – and two-tube radio receivers.

Bill Lear Jr. was so in love with electronics that his mother spent $50—more than a whole month’s rent—to hire a carpenter to build a smaller version of a “Menlo Park Edison Lab” in their backyard, as a way to make up for her ex-husband’s indifference to their son.

Lear recalls when his father flew to Miami in his Beechcraft Model 17 Staggerwing, in 1938, to participate in the Miami All-American Air Maneuvers. Excited to see his estranged father, 10-year-old Lear also anticipated the arrival of a “huge box of old radio parts” from his father’s factory, which was promised to arrive before the event.

“The only thing I cared about at the time was getting that box,” he said. “I started to hate my father for making false promises. Months went by; after Mom called him, I got the box. It was full of ‘useless’ wires and cables. It wasn’t easy having a famous dad; he didn’t understand how much a kid needed him, his love and his word.

“Dad was so busy with the things that he wanted to do that he just didn’t think to spend time with his children. He always underestimated himself; he always had that little problem, where he was trying to be better than the next guy. He was successful at doing it, but he always had a little inferiority complex. He made up for that by becoming such an extrovert.”

Wonderful Moya

By 1940, Bill Lear had invented the Learmatic Navigator, an automatic pilot system that kept aircraft on course by locking into radio broadcast signals. It earned him the prestigious Frank M. Hawks Memorial Award.

That year, his namesake, who had been failing public school, entered Howe Military School, in Howe, Ind., which he would attend for two years. Away from his mom for the first time, he was extremely lonely.

Two new women would enter his life after Bill and Madeline Lear divorced.

“After Dad divorced Mom, he married Margaret Radel, but it didn’t last long,” Lear said, recalling she was a “cheap, easy, gold-digging but sexy babe.”

Bill Lear married again in January 1942. Moya Olsen was the daughter of Broadway’s famous stage comedian Ole Olsen, of Olsen & Johnston in New York’s “Hellzapoppin” fame.

“Moya not only won Dad’s heart, but mine too,” Lear said. “Mom was in Missouri, so I couldn’t see her much, but Moya took me under her wing. She’d drive up to be with me at Howe for every major ceremony and was always there to pick me up at vacation times.”

Bill and Moya Lear would have four children together: John Lear was born in 1942, Shanda in 1944, David in 1948 and Tina in 1954. Later, Lear Jr. lived with his father and Moya in Piqua, Ohio, where he worked after school at Lear Inc., which made fighter and bomber aircraft electric actuators.

In 1949, Bill Lear relocated his plant to Grand Rapids, Mich., where he developed and tested the F-5 autopilot. During WWII, he became a major supplier of technological equipment to the Allied forces. After WWII, he perfected his autopilots for fighter jets, and added a system for fully automatic landings in low-visibility conditions.

In June 1956, flying his twin Cessna into Moscow, with Moya, he was the first private pilot allowed to land in the Soviet Union.

Bill Lear Jr.—Bendix Race and beyond

On May 17, 1946, Lear Sr. gave his son $1,250 (plus $75 for two 165-gallon drop-tanks), which paid for his son’s “love of his life,” an all-new P-38L from Kingman Army Air Field, Kingman, Ariz.

Lear also owned an AT-6, which he said meant “absolutely nothing to him” after he got his P-38. He had plans to fly his twin-engine P-38 in the 1946 Bendix cross-country race from Van Nuys, Calif., to Cleveland, Ohio. He named his plane “The Martha J,” honoring his wife-to-be, Martha Joy (McKee) Crawford, whom he married on Sept. 14, 1947. He was 19 and she was 18.

On Aug. 30, 1946, he became the youngest person to fly in the Bendix Race. He didn’t win, but he still beat out two other more experienced P-38 and Corsair FG-1 pilots. “Billy the Teenage Kid & His P-38” was his official booking as he took up air-show flying and other escapades.

Tony LeVier, the former chief experimental test pilot at Lockheed Aircraft Corp., and designer and builder of the P-38 fighter, took young Lear under his wing, quizzing him and talking to him about all the aerobatics he tried.

“Tony watched out for my back; he was a dear friend,” Lear said. “He was the ‘king’ of P-38 air shows, flying his bright red ‘Yippie’ P-38L.”

He said LeVier, who later wrote the foreword to his autobiography, was the first person in the world to privately own a P-38.

With LeVier’s help, Lear was soon skillful at various crowd-pleasing maneuvers, but his father convinced him that he should give college a shot. He told him that if he attended Glendale Junior College, he would pay him a monthly stipend. But one day Lear was called into the dean’s office, and warned that his father had given orders he was to be kicked out if he were absent more than once.

“I was furious that Dad had so much power,” Lear said. “I couldn’t believe that he could even tell a public school what to do. I was so angry I quit school then and there.”

Deciding he wanted a “real education,” he returned to flying full-time, until he was involved in a serious crash. During an air-show performance, after losing both engines, he crashed onto the boundary fence and slid up to the runway on the P-38’s belly. He wasn’t injured, but his aircraft was wrecked that day in Twin Falls, Idaho, on July 20, 1947.

“I loved that plane,” he said. “It was one of the saddest days of my life.”

He found another P-38, and flew it in the 1947 Bendix Race, making him the youngest pilot to have ever flown in that prestigious contest as well. He also set an air speed record, when he performed a stunt for an air show to benefit Navy relief and flood victims.

The military

When Bill Lear Jr. decided to join the military, he knew he didn’t want to be in the Navy.

“All of my life I’ve been fearful of water—swimming in it or drinking it,” he said. “I nearly drowned as a child.”

In 1948, at age 20, he was accepted for Air Force pilot training, subject to passing a college equivalence test and a physical. He reported to March Field in California, where he aced the equivalency test, but flunked the physical exam. His right nasal passage was 80-percent blocked as a result of breaking his nose as a child. After undergoing painful nasal surgery, he passed the physical.

He said he thought his dad was proud of him for joining up, but that he didn’t believe he’d be able to cut it.

“He used to say that the only thing I ever finished that I had started was a bottle of beer,” Lear said. “But I knew I could prove him wrong.”

Assigned to Randolph Field in Texas, Lear graduated flight training with the class of 49-C, but not before coming close to losing his flight privileges or being thrown out of the program. He lied about his piloting experience, telling his flight instructor he only had 50 hours in a Piper Cub.

True, on May 27, 1944, three days after turning 16, he soloed in a 50-hp Piper J-3 Cub, after eight hours, 10 minutes of dual instruction time. But when he joined the military, he had over 1,000 flight hours, including time in the P-38, AT-6 and BT-13, as well as a wooden-fabric Stinson JRSR and a Cessna T-50. And he had earned his instrument and multi-engine ratings in August 1946.

“But there I was, signed up to ‘learn how to fly’ in an AT-6,” he laughed. Fearing “more hazing,” he lied because he didn’t want to appear as a “smart-ass, know-it-all” pilot.

Lear was assigned to Las Vegas Air Force Base (now Nellis AFB) for advanced flight training. In the second class to occupy the base since WWII, he would learn the basics of the P-51D Mustang.

“The afternoon sun produced furnace-like temperatures up to 120 F; the planes got so hot sitting on the ramp, we had to wear gloves so we wouldn’t burn our hands,” he said. “Inside the cockpit, it got up to 150 degrees; we were severely dehydrated. And those low-level missions were hell—sitting under Plexiglas canopies.”

He believed that was one of the reasons his flying class had such a high accident rate—the highest of any previous class.

“We were killing a student every few weeks, plus having an extremely high incidence of survivable crashes,” he said. “We were constantly attending funeral services. In fact, our flying class of 49-C became known as ’49-Crash!”

On Sept. 20, 1949, 10 days to graduation and getting his wings, he flew the number-two position in a high-altitude, formation flight of three during a Vee exercise from the base. The leader leveled off at 30,000 feet; as Lear and another cadet followed his direction, he began giving signals for them to change positions.

“There were usually about 60 Mustangs in the air at any given time, and it was impossible for all of us to use the radio, as our ARC-3 VHF radios only had eight frequencies back then,” he said. “We did have a common training frequency, to use in the event of an emergency, but we used hand or aircraft movement signals while we were simulating combat radio silence.”

He said they were approaching Mt. Charleston northwest of Las Vegas still at 30,000 feet, when the leader signaled for left echelon.

“I was designated to fly in the number two position, so I dropped down and under Murray’s aircraft and waited for Andy Wilcox (the other cadet) to move out so I could take his place, then Andy would move back, flying on my wing,” he explained.

That didn’t happen; Wilcox, who hadn’t seen Lear, decided that he must be number two, and began to slide back into his original position, but as Lear moved up into position, the two aircraft collided.

“The next thing I knew, his 16-foot prop came down through the top of my canopy, right behind me, slicing the back of my seat rails off,” he said. “When you’re at 30,000 feet, your helmet and mask blown off, and with only a half a plane left, it’s damn cold and windy!”

When their aircraft collided, both planes popped up vertically, and locked together. Wilcox bailed out of his plane at about 25,000 feet and immediately opened his chute.

“Our instructor thought I was dead; he only saw Andy’s chute,” Lear said. “Both aircraft hit the ground and exploded, but they didn’t see my chute because I had managed to bail out and was freefalling.”

He said that before he bailed out, the front end of his plane was spinning down like a top.

“I was stuck; my face was on the instrument panel because my seat was pressing against me,” he said. “The only thing I could see through my peripheral vision was a lot of rotating sky. I smelled raw fuel; being trapped in a fire is every pilot’s worst fear, and when you’re spinning like that, G forces are tying to keep you in place.”

Lear tried to kick his seat away, but it wasn’t an easy task.

“I was hanging outside the ass-end of the aircraft, and the wind was trying to drag me out,” he said.

Similar to a surfer catching a wave, he rolled his body to the right, catching the inside of the turning spin, and freefell downward. He joked at least he had presence of mind to wait to deploy his chute.

“I guessed that I was about 500 feet from the mountainous terrain, but I delayed because the tail-end of my aircraft was chasing me; I was fearful it might hit my chute when I pulled the ripcord,” he said.

Miraculously, neither men suffered serious injuries. Even after that experience he didn’t think about quitting.

“The thought of quitting never occurred to me,” he said. “The next day I was flying again without any fear whatsoever.”

In September 1949, Lear graduated flight training as a second lieutenant in the Air Force. His mother attended the ceremonies and pinned his silver wings on his uniform.

“I was disappointed that my father wasn’t there to watch me finish something other than a bottle of beer,” he said.

Later, Lear Sr. gave him a check for $1,800 as a graduation present.

Germany—surviving a “Hawg” crash

Bill Lear Jr.’s first assignment was north of San Francisco, at Hamilton Field, where he flew F-84D Thunderjets in the 84th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 78th Fighter Interceptor Group. An Allison J-35 axial-flow turbojet engine, with about 5,000 lbs of thrust, powered the F-84D, a Republic Aircraft design. The heavy airplane was dubbed the “Hawg.” Lear said the engine had serious reliability problems.

“Like exploding!” he said.

Although he was destined to the Far East, the Korean War had broken out, and Lear’s second wife, Ann Davis, demanded he apply for a transfer to Germany instead. Relying on his father’s connections, in May 1950, the Lears were on their way to Germany, which the 22nd Fighter-Bomber Squadron (the “Bumblebees”), 36th Fighter-Bomber Wing at Furstenfeldbruck AFB, would call home for the next three years.

Lear piloted old F-80s until September 1950, when 75 new Republic F-84E Thunderjets were delivered to bases.

“It was better than the ‘D’ model, but still a Hawg,” he said.

The single-engine F-84Es had a history of catastrophic failures, with problems particularly in the areas of structure, controls and ejection seats.

“The two fighter wings we had in Germany were there to run intercept missions on the Warsaw Pact nations, who would probe our radar defenses by flying into West Germany from Czechoslovakia,” he said. “We never knew if they were probes or real attacks; we were always on alert—literally. We all thought this was a joke, as we only stood-by in daylight hours; we didn’t have means to intercept at night. Even though the Commies were flying MiG-15s, with loaded guns, we weren’t! We couldn’t have defended ourselves; we knew we’d get our asses shot down.”

He said MiGs were no match for their F-84s, but under no circumstances were they to engage the enemy.

“We were told to eject, if we couldn’t stop MiGs from bearing guns on us,” he said. “We certainly couldn’t return fire; our guns were loaded, but ‘uncharged’—with no means to charge them in the air. We were also given additional orders. If when airborne, Germany should be attacked by the Soviets, we were told to fly a heading of 300 degrees, which would take us to England, and land anywhere. Why the Soviets didn’t invade Germany is a mystery. They could’ve overrun us in a matter of days.”

If it wasn’t MiGs gunning down unprotected F-84E pilots, it was Hawgs killing its own. Pilots were unable to eject, using modern equipment; there were micro-switch failures causing deaths to pilots, when canopies and ejection seats fired or the ejection system misfired. There were faulty elevator push-rods, too, and engine failures galore.

“No one in the Air Force wanted to own up to the fact that the F-84E/Allison J-35-17B engine combination was a disaster that was costing lives and the taxpayers a fortune,” he said.

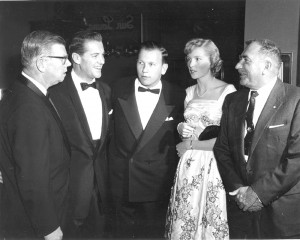

L to R: Actress June Allyson, Bill Lear Jr., actor Dick Powell and Martha Joy (McKee) Crawford, Lear Jr.’s fiancée, in front of his first P-38, “The Martha J” (Bendix Race, 1946).

Since F-84s were often grounded, Lear was checked out in every type of airplane on the base. At Hamilton AFB, in addition to flying T-6s, P-51Ds and F-84Ds, he flew T-33s, C-45s and C-47s. At Furstenfeldbruck he flew the T-33, T-6, C-47 and Douglas A-26 (renamed the B-26).

There were so many engine failures that after one in particular in 1952, after an F-84E was recovered from the Mediterranean Sea, its engine was removed and put on display with a large sign that read, “The Allison Time Bomb—$50,000 Worth of Junk.” Lear experienced “The Allison Time Bomb” firsthand, when his F-84E engine exploded!

“I was leading a gunnery team of four aircraft, and we took off with two 500-pound bombs, with proximity fuses, eight, five-inch high velocity rockets and 110 rounds of 50 caliber machinegun ammo,” he said.

On that day, he noticed his engine was running too rough, so he pulled the throttle to idle and zoomed up to 10,000 feet. While trying to alert Frankfurt that he would have to make an emergency landing, his message cut out and his engine exploded.

“The wings shook like cardboard in a 300-mph wind,” he said. “The instrument panel’s shock-mounts broke; it half fell out into the cockpit. I tried to contact my wingman but discovered that although my receiver was working, my transmitter wasn’t; the transmitter was blown right out of the plane.”

The 5,000-foot runway below wasn’t long enough for an F-84, even under normal conditions, but Lear went for it anyway.

“I sure wasn’t going to use the unreliable ejection seat,” he said. “Those cheap Air Force bastards only approved equipment for fighter aircraft allowing for one eight-channel VHF transmitter/receiver and one radio compass—finally. That was it. No backup electro-hydraulic pumps either.

“In the late fifties, commanding Gen. Curtis LeMay of the SAC, our nuclear defense force, had to purchase ‘civilian’ emergency radio communications equipment from our company, Lear Inc., to install in their B-47 bombers, because the Air Force wouldn’t provide them. These were purchased using local base discretionary funds and installed surreptitiously.”

Luckily for Lear, he wasn’t seriously injured.

“The next morning, when I reported for duty, I was castigated for dinging my aircraft!” he said. “I stood before my squadron, the squadron’s operations officer and its squadron commander, telling them I wouldn’t ever fly that deathtrap of an airplane again. Within a nine-month period, we had 69 engines explode, out of the 75 new F-84Es that were delivered.”

Switzerland: the P-16 & Learjet

After living in Germany for three years, Bill Lear Jr. moved to Geneva, Switzerland.

“My father first moved there in 1955; I followed in 1956,” he said.

Bill Lear commuted back and forth between corporate headquarters in Santa Monica, Calif., where he ran Lear Inc., and Geneva.

“I was occupied with Lear Inc. business as president of Lear S.A., overseeing sales of our automatic pilots, integrated flight systems and other products throughout Europe, the Middle East, Africa, etc.,” Lear Jr. said.

His prior military jet fighter experience would unwittingly become the catalyst for the SAAC-23, which would become the Lear Jet Model 23 and eventually be known as the Learjet.

“It was the 23rd design of my dad’s incredibly farsighted dream and fertile mind,” he explained about the name. “It was ‘the one’ that stuck, the one that captivated the business jet market. I’ve never seen a man so driven, so confident, so determined, and so damned right!”

As the aircraft was taking shape at Lear’s Swiss American Aircraft Corp., based in Geneva, in 1960, Bill Lear Jr. began working with Flug-und-Fahrzeugwerke Altenrhein, a private aircraft company owned by Dr. Claudio Caroni, who had designed and built five Swiss fighter-bomber prototypes of the P-16. The company hoped the Swiss government would buy them to replace the aging British Vampire and Venom fighters that its air force was currently flying. But earlier flight tests had resulted in accidents; the press nicknamed the P-16 the “Swiss Submarine,” as two of the aircraft had been at the bottom of Lake Constance.

Lear Jr. had a reputation as a “red-hot” Air Force fighter pilot, with about 5,000 hours flying time, and with 800 hours in jet fighters (he ended his flying career with about 7,500 hours TT). He was invited in March 1960 to evaluate the performance of the P-16.

He tested the P-16 on five different occasions. On his last flight, he had the aircraft at supersonic speed in a dive from 40,000 feet, Mach 1.05, and he ultimately pulled 8.5 Gs at 740 mph, exceeding the 5G-limitation warning. He said there was minor damage to the tail structure due to the high loads imposed on the structure when he “overstressed” the plane during his 8.5 G pull-up.

Although Lear had proven that the Swiss P-16 was sound, the Swiss government ended up purchasing Great Britain’s Hawker Hunter.

“I’d blown the pros at FFA out of the tub,” he said. “I was feeling damned proud of myself for being able to fly this marvelous piece of Swiss craftsmanship by the numbers. The Lockheed P-38 is the only other military aircraft that I’ve ever felt so at-home, so comfortable and so at-one with.”

He was so impressed with the P-16’s flight characteristics that he brought them to his father’s attention.

“It was originally anticipated Dad’s design of the SAAC-23 would be built in Switzerland, but it became obvious that the FFA’s factory would be an ideal place to accomplish this—since its project had been scrubbed by the government,” he said. “Dad made a deal with Dr. Caroni; they reached an agreement to begin work on the SAAC-23 prototype using Caroni’s labor pool.”

He said his father wouldn’t waste time or money with a hand-built, proof-of-concept plane built on ‘soft’ tooling.

“He built the ‘Learjet’ on hard tooling,” he said.

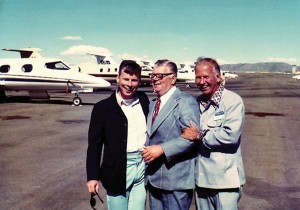

L to R: Bill Lear, actor Bob Cummings, Bill Lear Jr. and former wife Yola Lear, and Paul Mantz dine at the Beverly Hills Hotel in 1957.

Lear Jr. said he was thrilled that he’d been able to fly and evaluate the P-16, and proud that he was able to draw his father’s attention to the outstanding Swiss P-16 aircraft.

“That was my contribution to what was to become the world’s most famous business jet,” he said.

He adds that it’s a common misconception that the Learjet was a derivative of the P-16.

“That’s patently false,” he said. “For instance, the P-16 had Krueger leading-edge flaps for added lift; the Learjet doesn’t. The P-16 wing aspect ratio was around 4.15; the Learjet’s aspect ratio was 5.4; the P-16 wing sweep was zero; the Learjet’s was 13 degrees. The P-16 used double-slotted Fowler flaps that extended under the fuselage; it also had ailerons that could be drooped 18 degrees. The Learjet uses single-slotted flaps, confined to the wing area only, and it doesn’t have leading-edge high-lift devices or drooped ailerons.”

He said there are other “major” differences between the P-16 and the Learjet.

“The Learjet’s fuselage and tail were totally different; the P-16 had a cruciform tail while the Learjet has a ‘T’ tail,” he said. “The Learjet was a totally new, clean-sheet design using a few of the best features of the P-16. The P-16 utilized a multi-spar (8) fail-safe box-type wing design, as it was good for plus-13G and negative-9G load limits, which the Learjet used a modified version of.”

He said some of the P-16 wind tunnel data was used, but only due to the similarity of the Learjet’s wing airfoil that had already been designed.

“Other Learjet wind tunnel tests were conducted at Wichita University’s tunnel,” he said.

Watch out, Wichita

Lear moved the project from Switzerland to Wichita in 1962; the Lear Jet Model 23 was the first to roll off the new assembly line. Why did Lear leave Switzerland, when labor was half the price?

“Because it took too long to get anything done there,” Bill Lear Jr. said. “We didn’t have the money or time to waste. Wichita was very good to us. Cessna, Beechcraft and Boeing were all there with a highly experienced aircraft construction workforce. Wichita welcomed us with open arms. City fathers agreed to float a bond issue to finance the construction of the production and test facilities on land adjacent to the airport. They built a taxiway connecting these new facilities to the main airport infrastructure.”

Prior to Lear building the Learjet, he approached his board of directors to build the plane, but they flatly refused him. They laughed at his idea, believing it was impossible. In true Bill Lear fashion, he funded the project himself.

In 1962, the French government honored Lear for making automatic blind landings possible in passenger airplanes. That same year, he moved the Learjet project to Wichita.

“On Jan. 7, 1963, within six months of construction, the first Wichita building was completed, and Dad and 75 employees moved in to begin a remarkable achievement,” he said. “The Old Man pulled off a miracle.”

On October 7 of that year, Lear’s first prototype 23-001 took to the air, “just 10 impossibly short months after moving into the Wichita facility.”

“It was a mammoth undertaking for one man to have achieved, and the only time in aviation history that a project of this magnitude had been designed, driven and solely financed by a single individual,” he said. “It will probably never be repeated.”

The entire Learjet program from inception to certification cost Lear Sr. $12 million. The Learjet yielded $52 million in sales its first year.

Do or die

When Lear sold his aircraft company to Denver-based Gates Rubber Co. on April 10, 1967, 146 Learjets had been sold. Today, Bombardier Aerospace produces the Learjet. Sometime earlier, the Lear Star 600, a 12-place business jet, was designed. Canadair purchased the manufacturing rights and renamed it the Challenger.

Lear was now a very rich man, but that turned out to be a problem. He felt useless without having any problems to fix.

“We moved to Beverly Hills and bought this fabulous house,” Moya Lear said, in 1967. “I thought it was going to be forever.”

But one night, they went to dinner with friends, in the rain, and Lear slipped and fell.

“Shortly thereafter, he began to have nosebleeds; both of his eyes were black and his leg was broken and in a cast,” she said. “He was in despair; he didn’t want to live anymore. At one point, he thought about getting a plane—not a Learjet; he was too practical for that—but a nice cheap plane, and flying out over the Pacific and ending it all. He even left me a note…saying he loved me, but he couldn’t live like that.”

As she caught him trying to leave, she told him, “You’re behaving like an idiot; you have so much to be grateful for. You have a good head; there’s a need, more you can do. We’ll start over tomorrow.”

She said they “were fat in the bank,” but he was right; he couldn’t live like that.

“He needed a challenge, a world to conquer—an impossible dream to pursue,” she said.

Then, a friend told Lear there was a need for an alternate source to the internal combustion engine. America needed a more environmentally friendly means of locomotion, and Lear found a reason to live.

Letting off some steam

In 1968, Lear bought the old Stead Air Force Base at Reno, Nev., for $1.3 million, and established Lear Motors Corp. and Lear Avia Corp, which would develop his pollution-free steam engine.

“Because nothing had been done in 40 years, the technology for vehicular steam was partially nonexistent,” Bill Lear said, at 72. “What encouraged me was that I discovered 83 percent of the world’s power is generated by the means of steam. I found out that of the 83 percent of steam-powered devices, 95 percent of that was generated by some kind of turbine, so I found out that steam was practical—and that turbine was the answer.”

However, his invention had problems; huge turbine-powered steam engines worked for dams and ships, but to scale that down to fit under the hood of a car was another story. Lear tested his invention on a bus, logging 9,000 miles with his turbine-powered steam engine, for over six years. While it was pollution free, fit under the hood of a Chevrolet Monte Carlo and was reasonably fuel efficient, the EPA and Detroit managed to bury it.

Although Lear never gave up on his invention, he became interested in a new airplane design.

One Last Dream: The Lear Fan

“Bill didn’t like to hunt, fish or even play golf,” Moya Lear said. “It was a waste of time. He had to work and meet a challenge; when he met it, he was finished. He would work until he was exhausted, perfecting whatever it was that he was working on; he was born like that, born to meet a challenge.”

In the spring of 1977, Bill Lear had been working with a new material; we know it as “composite,” which promised the same strength as aluminum, at one-third less weight.

“Dad was never one to simply nibble at a problem; immediately, he foresaw a business aircraft constructed entirely from this revolutionary material,” Bill Lear Jr. said.

The Lear Fan Model 2100, an eight-place, fuel-efficient, turboprop—which promised fabulous speed and climb performance, also had load-carrying characteristics.

“The Old Man was off and running again—the design was completed, and the first prototype was under construction in the late seventies,” he said.

The Lear Fan was a “pusher,” with engines and prop at the rear of the aircraft.

“But then Dad died, just before his 76th birthday, which was doubly tragic because he and I had only found each other in the recent years, and he had so much more he wanted to accomplish,” Bill Lear Jr. said. “I’m convinced that had Dad lived, he would have made the Lear Fan a viable program, but probably would’ve abandoned composites, for the most part.”

John Lear—no fan of the Lear Fan, or of his father

John Lear’s speaking engagements are becoming quite popular. That’s because he’s brutally honest about his career mistakes—and he admits there are many—and about the venomous relationship he had with his father. It helps that he injects humor into his talks.

“One of the greatest laughs I get when I make speeches is when I talk about my father passing away,” he said. “I know he thought highly of me; he mentioned me 60 times—more than any of his children—in his will. After each paragraph, his will stated ‘…except John Olsen Lear.'”

When it comes to the infamous will, John Lear says he doesn’t really think it was his father who cut him from it.

“I believe that Mom forced him to cut me out because I was non-supportive of the Lear Fan project,” he said.

He said his father signed a “new” will while heavily sedated a few days before he died, and that his two sisters sued to bifurcate, which was successful in 1983. Monies that would’ve gone to him went to his children.

“I’m happy that my children received the money,” he said.

It’s been 27 years since Bill Lear died; John Lear says that “time passes and feelings soften.”

“If I could just take him in my arms and hold him for 15 seconds, I’d say, ‘Dad, I still think you were an asshole,'” he says.

So, what went wrong between him and his father?

“What went right? My dad was never a friend,” he said.

He recalls that his father reluctantly allowed him to fly on the round-the-world Learjet flight.

“He was under extreme pressure from Mom and Hank Beaird, a Lear factory pilot,” he said.

One thing Lear never understood is why his father never wanted him to become a pilot.

“He sent me to a shrink thinking I was nuts,” he said. “I don’t know why he felt that way; he did everything he could to stop me from becoming a pilot.”

At one point, it seemed like he should’ve listened to his father. On June 24, 1961, at 18, after he had just obtained his commercial rating, John Lear nearly died.

“I was showing off my aerobatic talents in a Bucker Jungmann to my friends at a Swiss boarding school I had previously attended,” he said. “I had managed to start a three-turn spin, but I was too low and I crashed. I shattered both of my heels and ankles and broke both legs in three places; I crushed my neck, broke both sides of my jaw and lost all of my front teeth.”

After getting gangrene in one of the open wounds in his ankle, he was shipped from Switzerland to the Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque.

“When I could walk again, I worked selling pots and pans door to door in Santa Monica,” he said.

Presently, John Lear, 63, owns and operates the only permitted gold mine operation, Cutthroat Mining Corporation, in Clarke County, Nev., where he lives with his wife of 34 years, Marilee Lear, who is the only licensed casting agent in Las Vegas. His efforts to clean up the Treasure Hawk Gold Butte mine won him the State of Nevada award for excellence in mining reclamation in 1999.

John Lear is well known in UFO circles, but he claims he’s wasted 20 years on the topic, and he doesn’t want to discuss it. His popularity within the UFO community has overshadowed his accomplishments as a 19,000-hour-plus commercial pilot. He’s flown in over 100 different types of planes in 60 different countries around the world. He’s the only pilot to hold every FAA airplane certificate, to include an airline transport pilot, flight instructor, ground instructor, flight navigator, engineer, aircraft dispatcher, A&P mechanic, parachute rigger and tower operator. He holds 18 world speed records, including a speed record for a round-the-world flight in the Learjet in 1966.

He was the youngest American to climb the Matterhorn in Switzerland, in 1959, and in the seventies he owned and skippered the America’s Cup boat, the “Soliloquy,” out of Marina Del Rey, Calif.

Bill Lear Jr. said his half-brother was a good pilot, and that he and his father didn’t see eye-to-eye on anything.

“John was highly critical of the Lear Fan program; he made no bones about telling the Old Man he was dead wrong about the project,” he said. “I’ve told John, ‘If it’s any consolation, you were cut out of the will, but you were right!'”

Bill Lear’s namesake “does” believe his father cut John out of his will over the Lear Fan.

“I think Dad finally had enough,” he said.

John Lear worked for 28 different aircraft companies, and admits that he’s been fired from most jobs he’s had.

“I don’t mind telling everyone about all the things I did wrong, all the people who fired me and why all the companies collapsed,” he says. “Why did so many people fire me? Truthfully, I’m not the brightest crayon in the box; I’m extremely lazy, I have a smart mouth and a real poor f—ing attitude, but everybody loves that truth. Often, they say, ‘You’ve got to hear this guy.’ Not everyone goes around telling people they’ve been 321 miles off course; most people don’t talk about all the mistakes they’ve made. They like to glorify their accomplishments, but I’m telling it like it is; I spent most of my life screwing it up!”

Brother Bill jokingly added, “I think John is being far too modest.”

Postscript

After Lear’s death on May 14, 1978, Moya Lear (who died in 2001) became chair of Lear Avia, and took over the Lear Fan project with gusto—because she loved him, and because that was her husband’s last request, and his last dream.

The Lear Fan program, along with private domestic and foreign investors, would cost $240 million, before its demise just months before certification in 1985. This was a blow to Bill Lear Jr., too, as he stood to make about $6 million from commissions.

“We had three prototypes—three albatrosses around our necks,” Lear Jr. said. “Prince Sultan, our latest financial benefactor, folded his tent and disappeared. He, as well as the British, saw the handwriting on the wall; the price of the Lear Fan had escalated from $850,000 to $1.8 million.”

Another reason he believed the Lear Fan project would’ve been successful, if his father had been alive, was his simple genius.

“He was a good listener, and a good student,” he said. “When he wanted to go out for certain projects he’d surround himself with good people and pick their brains. For instance, he could take a guy that was a physicist, and my father would extract just that bit of information that he was interested in from that guy—bypassing 30 years of experience from a guy like that, and then run with that. Using that method of extracting only information he wanted, Dad became an expert on any particular subject within two weeks; that was his genius. I was so fortunate to have been his son. I’m so proud of him.”

After living 20 years in Geneva, Bill Lear Jr. spent five years in Britain, where he did “spook work,” after the Lear Fan project went belly up in 1985. A self-admitted serial husband, Bill Lear Jr., 77, has been married five times, but he attributes that to Lear genes, too.

“I’m a lot like the Old Man; we both liked the dollies,” he grins.

Lear and his wife of 12 years, Brenda, currently reside at Spruce Creek Fly-In near Daytona Beach, Fla., a well-known aviation community.

“I can’t fly anymore due to diabetes and some disturbing vertigo,” he said. “But I’ve got an infallible memory, my Brenda and my many friends; I’m one lucky dude.”

To purchase Bill Lear Jr.’s autobiography, “Fly Fast, Sin Boldly; Flying, Spying & Surviving,” visit [http://www.billlear.com]. For information on John Lear’s aviation speaking engagements, contact Bruce Merrin’s Celebrity Speakers & Entertainment, Inc. at [http://www.celebrityspeakersentertainment.com].