By Stuart Leuthner

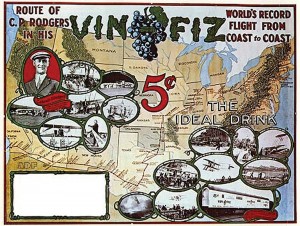

The Armour Company sponsored Cal Rodgers’ cross-country flight to promote Vin Fiz, its new grape drink. He made the flight in a Wright Model EX biplane.

In October 1910, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, an early fan of aviation, announced he would award a $50,000 prize to the first pilot to complete an aerial crossing of the United States in 30 days or less.

At the beginning of the 20th century, flying was considered a sport for daredevils. Pioneer aviators risked life and limb in their primitive airplanes, and the majority of flights were little more than stunts to entertain crowds at fairgrounds. The idea of a cross-country flight seemed like something out of a Jules Verne novel.

Landing fields were glorified pastures. No maps, beacons, on-board instruments, radios or weather forecasts were available to help guide a pilot attempting even a short cross-country hop, much less a flight from coast to coast. The only navigational aids were railroad tracks, known to early aviators as the “iron compass.”

By the fall of 1911, three competitors, Robert Fowler, James Ward and Cal Rodgers had announced they would attempt the flight. The first to take off was Fowler, who left San Francisco on September 11, in a Wright biplane powered by an engine manufactured by the Cole Motor Car Company. The automobile company’s executives hoped that publicity generated by the flight would help sell their cars.

Attempting to fly through Donner Pass, Fowler was flying at 8,000 feet when he encountered extreme turbulence and his radiator boiled over. After several attempts, he was forced to turn back for repairs. He made the decision to attempt the flight later.

James Ward, flying a Curtiss Model D, left Governor’s Island in New York Harbor on September 13. He got lost over New Jersey and developed engine trouble. After flying only 20 miles, he crash-landed. After repairs were made, Ward took off again, only to crash again in western New York. His wife convinced him to abandon the flight when they discovered gamblers were giving five-to-one odds that he would be killed before he reached Buffalo, N.Y.

The third aviator, Calbraith “Cal” Perry Rodgers, was born into a wealthy family in Pittsburgh in 1879. Rodgers was a descendant of several naval heroes. His grandfather, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, sailed to Edo (modern Tokyo) in 1854, and opened up U.S. trade with Japan. His granduncle, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, was the hero of the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812, and penned the famous words, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.”

Rodgers’ early years were difficult. His father, an Army officer serving in the western United States, was killed by lightning five months before his son was born. When Rodgers was 6, he caught scarlet fever, and as a result, suffered major hearing loss.

Rodgers wanted to attend the Naval Academy, but was turned down because of his disability. He enrolled at Columbia, where he excelled at football, but left after one year. He married Mabel Graves, the daughter of a wealthy New England businessman, and settled down in New York City to enjoy the life of a gentleman sportsman. A member of the New York Yacht Club, he sailed as a crewman on other members’ boats, raced automobiles and motorcycles and searched for gold in Africa.

There’s nothing like it

In 1911, Rodgers traveled to Dayton, Ohio. His cousin, John Rodgers, a naval lieutenant who would become the U.S. Navy’s second aviator, was taking flying lessons at the Wright brothers’ school. According to one account, his cousin told Rodgers, “There’s nothing like it. You’re up there, watching the land glide by, bobbing, dipping as if in a boat, but you can see nothing, only feel it. For speed, you can’t beat flying.”

A short time later, Cal Rodgers, 32, began flying lessons with Orville Wright. After only 90 minutes of instruction, he declared that he was ready to solo. Wright disagreed and told him he needed more lessons. Rodgers asked the price of a Wright Model B and bought an airplane for $5,000; it was the first aircraft sold by the Wrights to a private individual. Rodgers climbed into his new airplane. After a shaky takeoff and 10 minutes in the air, he managed to get back on the ground in one piece.

On Aug. 7, 1911, Rodgers obtained a flying license, becoming the 49th man to be so recognized by the Aero Club of America. Three days later, he arrived in Chicago to take part in the Chicago International Aviation Meet. Competing against the world’s foremost aviators, he won the duration event for remaining in the air an amazing 27 hours and won $11,285.

While in Chicago, Rodgers heard about the Hearst prize. Realizing he needed a sponsor, he visited J. Ogden Armour, the president of the Armour Company, and asked if he would like to sponsor his cross-country flight. At that time, Armour was coming out with a new carbonated grape drink, Vin Fiz, and needed a promotional gimmick. Armour agreed to pay Rodgers $5 for every mile he flew east of the Mississippi River, and, because the west was more sparsely populated, $4 dollars for every mile west of the river.

The company also assembled a train that would serve as a support base during the flight. A private Pullman car provided sleeping and dining accommodations for Rodgers, his wife and his mother. A second Pullman car housed Rodgers’ business manager, three mechanics, several Armour employees and members of the press.

The chief mechanic was Charles Taylor. Taylor had worked for the Wright brothers since 1901, and built the engine that powered the Wright Flyer at Kitty Hawk. The Wright brothers told Rodgers he should hire Taylor, saying, “You’re going to need him!”

A baggage car was converted into a rolling hangar and workshop. In addition to extra parts, fuel and oil, the car contained a Palmer-Singer automobile used to pick Rodgers up after each landing. Painted white, the sides of the baggage car were emblazoned with advertising promoting Vin Fiz and the flight.

In addition to the Vin Fiz endorsement, Mabel Rodgers, who attempted to obtain the official title of “postmistress,” raised money by selling special 25 cent postage stamps. Cards or letters bearing this stamp were carried aboard one leg of Rodgers’ flight. The U.S. Post Office tolerated the Vin Fiz stamps, but required that the mail had to also carry regular stamps if the writers wanted them delivered. Only 13 of the stamps are known to exist: eight on postcards, one on a letter and four off cover. One of the cards was sold at auction in 1999 for $88,000.

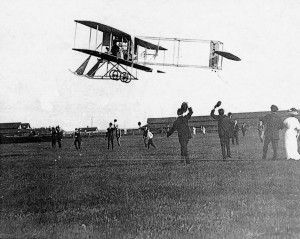

The airplane Rodgers flew was a Wright EX, a smaller version of the Model B, preferred by exhibition flyers. It had a wingspan of 31 feet and weighed 903 pounds. Constructed of spruce and reinforced with wire, the framework was covered with cotton duck fabric sealed with linseed oil. The airplane’s bottom wing, stabilizer and rudders carried advertising for “Vin Fiz, The Ideal Grape Drink.”

A water-cooled, Wright four-cylinder engine producing 35 horsepower supplied power. Bicycle chains drove two eight-foot wooden props. A 15-gallon fuel tank allowed three hours of flying time at a top speed of 55 mph.

At 4:30 p.m. on September 17, Cal Rodgers, dressed in a business suit and tie, several sweaters and a sheepskin vest, took off from the racetrack at Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. Clenched between his teeth was his ever-present El Ropo cigar. A bottle of Vin Fiz was strapped to a strut.

He circled over Coney Island, dropping promotional cards touting the grape drink and his flight, and then headed west, flying over Manhattan. Traffic came to a standstill, and office workers leaned out of windows as New Yorkers marveled at the sight of an airplane high above the city’s skyscrapers.

Crossing the Hudson River, Rodgers flew northwest and spotted his train on the tracks of the Erie Railroad. He followed it to Middletown, N.Y., where he made his first landing. The 105-mile flight had taken an hour and 44 minutes. To a jubilant Rodgers and his entourage, winning the Hearst prize appeared to be a walk in the park. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

When Rodgers took off the next morning, a gust of wind caused him to hit a tree with a wing, and he crashed into a farmer’s chicken yard. He climbed out of the wreckage with just a scalp wound. The Vin Fiz fared much worse; it required two days of around-the-clock work by his mechanics to repair the airplane.

Advertising for Vin Fiz appeared on the Wright Model EX’s landing gear braces, and on the bottom of the lower wing, stabilizer and rudder. Both Cal Rodgers (right) and his cousin, John Rodgers, took lessons at the Wright brothers’ school.

Back in the air again, Rodgers made it as far as Hancock, N.Y., before his engine began to act up. Wind continued to be a problem, but he pressed on. He landed at Binghamton on September 21, narrowly missing a fence after almost colliding with a flock of crows. Once on the ground, he often had to stand guard over his airplane. Sightseers attempting to write their names on the wings would punch holes in the fabric, or simply pry off a part to take home as a souvenir.

The next day’s flight was cut short when Rodgers once again experienced engine problems as he flew over Elmira, N.Y., and had to make a forced landing. Repeating a process that would become much too familiar, he and mechanics worked feverishly to repair the Vin Fiz.

Leaving New York and Pennsylvania behind, Rodgers was soon over Ohio, headed for Akron. Still plagued by the wind, he was blown off course and lost sight of the railroad. As the sun began to set, he realized he was in big trouble. Not only had he never flown at night, but no lights were on his airplane, and he saw none on the ground.

Somehow, he managed to keep flying until the moon rose from behind a cloud. After landing in a pasture, he climbed out of his seat and discovered he wasn’t alone. A herd of curious cows surrounded the Vin Fiz. A few of them began to chew on the airplane, and Rodgers spent a long night chasing the bovines away.

When the sun came up, Rodgers discovered that he had landed near Kent. Back on course, he flew into a series of thunderstorms and was hard pressed to keep the bucking Vin Fiz airborne. Once he was out of the storms, things improved and Rodgers was soon in Indiana. As luck would have it, however, he hit a fence while landing at Huntington, Ind., and destroyed both propellers, a wing and the landing gear.

Rodgers presses on, prize or no prize

Once again, the mechanics put the Vin Fiz back together, and Rodgers arrived in Chicago on October 8. Everyone involved with the flight realized that the Vin Fiz would never reach the Pacific Ocean in time to win the Hearst prize, but Rodgers was determined to press on. When a reporter asked him if he was going to quit, he replied that he was bound for the Pacific Ocean, “prize or no prize.”

“If canvas, steel and wire hold together with a little brawn, tendon and brain . I mean to get there,” he said. “I am going to cross the continent simply to be the first to cross in an aeroplane.”

At stops along the way, Rodgers dropped handfuls of leaflets and put on a display of aerobatics for the crowds that gathered to wish him well. As he approached towns, church bells rang and factory whistles sounded to alert the citizens that the “Iron Man” and his amazing Vin Fiz would be flying overhead. When he flew over Joliet Prison, the warden allowed the prisoners to stand in the yard, and Rodgers treated them to a few stunts.

Now flying southwest, the Vin Fiz landed in Kansas City, Mo. While Rodgers was between Kansas City and Muskogee, Okla., the clock ran out on the Hearst prize. He crossed Oklahoma and was soon in Texas, but the trip was beginning to wear on both the man and machine. It took two weeks and 23 stops to cross Texas, since he had to follow the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad, rather than flying in a straight line.

In Tucson, Rodgers met Robert Fowler. After abandoning his first attempt, Fowler was now flying a southern route and became the second pilot to cross the country, when he rolled the wheels of his airplane into the surf at Pablo Beach, Fla., on Feb. 17, 1912.

Shortly after Rodgers crossed from Arizona into California, disaster struck again. The engine blew a cylinder, and both pilot and airplane were doused with hot oil. Several steel splinters lodged in his right arm. Fighting to keep his airplane under control, he landed in the California desert. A doctor ministered to him while his mechanics repaired the engine. The next day, the airplane had to be pushed and carried more than four miles to find a suitable place where Rodgers could take off.

Aloft again, the intrepid airman headed for Palm Springs and the 2,600-foot San Gorgonio Pass. As he struggled to keep the tiny plane aloft, more problems occurred. Not only did the radiator spring a leak, but the magneto wires began to shake loose as well, causing the engine to miss. Rodgers landed in a plowed field, and the airplane suffered minimal damage.

Again, the Vin Fiz was repaired, and Rodgers took off on the morning of November 5. The observatory at Mount Wilson trained its 60-inch telescope towards the east, hoping to catch a glimpse of the approaching airplane. A crowd of more than 20,000 waited at Tournament Park in Pasadena for his arrival.

At four o’clock in the afternoon, the Vin Fiz arrived over the racetrack and the spectators cheered as Rodgers circled the field. E.W. Hewson, one of the reporters who traveled on the train wrote, “Spiraling downward from dizzy heights above, the greatest aviator in the world, who by sheer force of will and nerves of steel, had accomplished the impossible, stepped out from among his frail fabric of wood, wires and canvas, to be wrapped in the American flag. .”

In an interview with a reporter, Rodgers stated, “I don’t feel much tired. The trip was not a hard one, all things considered. Indeed, I believe that in a short time we will see it done in 30 days, and perhaps less. I was never worried at any stage of the game—not even when it looked as if it was all off. I knew I’d get through, even if only to show up the fellows who laughed at me.”

During the ordeal that would last 84 days, Rodgers’ actual flying time was a little over 82 hours. Although the number of crashes was never recorded, they numbered somewhere between 16 and 39. He made 69 stops.

Determined to reach the Pacific Ocean, Rodgers and his mechanics overhauled the Vin Fiz. On November 12, he took off from Pasadena, bound for Long Beach. Near Compton, however, the engine quit and Rodgers crashed while attempting to avoid power lines. The Vin Fiz was almost totaled. During much of the transcontinental flight, Rodgers was covered in one or more bandages. He suffered numerous cuts, bruises and abrasions, but this time his injuries were serious: a broken ankle, a badly sprained ankle, broken ribs, severe burns and a concussion.

After an almost complete rebuild, the Vin Fiz was ready to fly on December 10. Rodgers, with both ankles in plaster casts, lashed his crutches and the indestructible bottle of Vin Fiz to the airplane’s struts and flew the last few miles to Long Beach, where he rolled the airplane’s wheels into the Pacific Ocean.

The only original parts of the Vin Fiz to survive the trip were one rudder, one wing strut and the engine’s oil pan. Charles Taylor’s records state that they had replaced six sets of wings, two radiators, two engines, eight propellers and four propeller chains, as well as countless struts, skids, control wires and miscellaneous parts, and yards of fabric. The flight cost Armour $180,000, with Rodgers receiving $23,000.

Cards or letters bearing the special 25 cent Vin Fiz stamp were carried aboard one leg of Rodgers’ flight.

Cal and Mabel Rodgers remained in Pasadena, and he was crowned king of the Tournament of Roses Parade. Rodgers had carried his original Wright Model B in the baggage car on the trip west. He assembled the airplane, and in January 1912, flew along the parade route, dropping carnations onto the crowd.

Three months later, he took the airplane up for a test spin and crashed into the surf at Long Beach, less than 100 yards from where the flight of the Vin Fiz had ended. When rescuers reached him, they found Rodgers dead of a broken neck. Although no official reason for the crash was established, some observers believed that Rodgers flew into a flock of seagulls, and one of the birds became wedged in his control surfaces.

The fate of the Vin Fiz

Today, you can see the Vin Fiz hanging in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C. However, the aircraft’s history is unclear.

According to the Smithsonian Institution, after Rodgers’ death, Lt. John Rodgers acquired the Vin Fiz. Reportedly, he offered it to the Smithsonian Institution, but it wasn’t accepted because it was too similar to the recently acquired Wright Military Flyer. By then, Mabel Rodgers had married Charles Wiggin, and they exhibited and flew the aircraft publicly for two years. She was awarded possession of the Vin Fiz in 1914, in a court ruling.

From that point, the Smithsonian relies on the account given by Charles Taylor. He recalled that Rodgers’ mother shipped the Vin Fiz to the Wright factory in Dayton, Ohio, for refurbishment. Possibly because she was unable to pay for the work, she allowed the airplane to languish at the factory. Taylor claimed the aircraft was destroyed in 1916, after the company was sold.

The Smithsonian acknowledges that Taylor’s version conflicts with the fact that Rodgers’ mother had the aircraft restored and donated it to the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, in 1917. The Smithsonian acquired the airplane 17 years later.

According to the Smithsonian, the probable explanation for the conflicting information lies in the misconception that there was a single Vin Fiz airframe. Because of all of the crashes and rebuilds, almost nothing original remained of the airplane when Rodgers crashed that final time. While he was making his transcontinental flight, however, several sets of wings and many other components and parts were carried on the train. As a result, enough flown, genuine Vin Fiz parts were available to make up more than one airplane.

The Smithsonian believes that Taylor was probably accurate when he said the Vin Fiz sent to the Wright factory was destroyed. The airplane that ended up at the Carnegie Institute, and then the Smithsonian, was likely reconstructed from the parts left over from the many repairs and rebuilds during the flight. Believing that to be true, the Smithsonian says that the airplane in the NASM collection, which was fully restored in 1960, is genuine.

An accurate reproduction of the Vin Fiz is displayed at the Cradle of Aviation Museum, located in Garden City, N.Y., which celebrates Long Island’s contribution to aviation. Displayed with the airplane is a collection of memorabilia connected with the flight, including an original Vin Fiz soda bottle.

These displays are a reminder of the daring pilot who, against all odds, managed to crash his way across the United States. Calbraith Perry Rodgers is buried in Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Cemetery. Engraved on his tombstone are these words: “I Endure, I Conquer.”