By Cliff Robertson

Frank Tallman and Paul Mantz—two legendary pilots—were a perfect team. Paul, the older of the two, had already established himself as Hollywood’s premier film flyer. In addition to heeding filmdom’s needs, he managed to establish the world record for outside loops. A tribute to his eye sockets, as well as his flying skills.

They linked up shortly after World War II and gave birth to TallMantz Aviation in Orange County, then surrounded by orange trees. I descended on them in the mid-1950s, when I left my Actor’s Studio cocoon on West 44th Street in New York City. I had been lured out of my actor’s sanctuary to act in the film version of William Inge’s prize-winning play “Picnic,” still running on Broadway. No sooner had I dumped my suitcase in pal Jimmy Dean’s garage-pad on Sunset Plaza Drive, I headed south to review and pursue my true boyhood dream, interrupted by World War II.

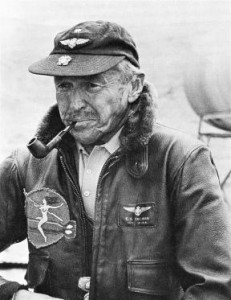

Dapper Frank Tallman was perfect for Hollywood. His flying skills were consummate, matched only by his personal “style”—similar to partner Paul—right down to elegant, perfectly trimmed “Roscoe Turner mustaches.” A famous race pilot, Roscoe had recently retired to his Indiana roots, leaving Frank and Paul to continue the flash-and-dash image still prevailing. Happily, “Smiling Jack” of the comics supported that image as well.

I had never lost my love for aviation. Since boyhood, aviation had a continual grip on my heart. Nothing—certainly not Hollywood—would ever break that hold. Come weekends, while other Hollywood actors were headed for film pool parties, I headed for TallMantz Aviation, where the allure was hypnotic. Aircraft, pilots and mechanics. Not an agent, producer or bimbo in sight.

Just why I had been accepted in their flying fraternity, I’m not sure, but in three decades, my love for aviation had never wavered. It was a constant true love. That fidelity has never flagged. I have been blessed by friends in aviation whose loyalties are not dependent on film “grosses.”

Certainly, Frank and Paul had to keep up their Hollywood appearances. After all, there were expenses. But in Paul’s backroom office, where close buddies gathered, there would be found leather flying jackets and mechanics’ overalls—not an Armani suite in sight.

After “Picnic” came other films and continued trips west from New York City. But I could never release my hold on aviation—or its hold on me. One fateful Saturday, I was waiting for Frank to go flying in his Stearman open-cockpit biplane—a survivor from World War II cadet training. Normally, Frank was punctual—a quality generated as much by personal consideration as refined background. But on this particular Saturday, he was late. Very late.

Normally, he would fly from Torrance Airport near his house in Palos Verdes to avoid traffic (even then). He kept a small Ercoupe at Torrance Airport, now the home of Robinson Helicopters. Some two hours passed when, finally, Frank called. The following was our conversation, as I remember it:

Frank: “Hello Cliff?”

Cliff: “Hi Frank.where are you?”

Frank: “Torrance Hospital.”

Cliff: “Hospital! What Happened? Did you crash the Ercoupe?”

Frank: “Not exactly!”

Cliff: “Not exactly!”

Frank: “No. It was the go-kart.”

Cliff: “The go-kart! You crashed the go-kart?”

Frank: “Yeah. Well, not exactly.”

Cliff: “Not exactly…”

Frank: “Well, Lance needed a push.”

Cliff: “Your son, Lance?”

Frank: “I gave him one. He’s fourteen.”

Cliff: “Yeah, I know.”

Frank: “So, I got out of my car…”

Cliff: “O.K.”

Frank: “To push him.ya know?”

Cliff: “Sure.”

Frank: “And I.and I.”

Cliff: “Yeah.”

Frank: “And I broke my leg.”

Cliff: “No!”

Frank: “Yeah. So you’d better go on without me.”

Cliff: “I don’t think so. I’ll come to the hospital.”

Frank: “No, Cliff. I’ll call you later. No big deal.”

Cliff: “A broken leg is a big deal, Frank!”

Frank: “Not really. After all, I am a stuntman.”

Frank Tallman was also a brave man. A very brave man. The next three days were more painful. More phone calls denying he needed my presence. Finally, the following:

Frank: “Hello, Cliff?”

Cliff: “Yeah. How’s it going, pal?”

Frank: “It’s gone, buddy…outta here.”

Cliff: “What?”

Frank: “That leg. The one I broke. It’s history.”

Cliff: “No! What happened?”

Frank: “An infection set in. They said it was best to cut it off.”

Cliff: “No! So…”

Frank: “So I said, ‘Cut the damn thing off!'”

Cliff: “No!”

Frank: “No big deal. I’ll still be able to fly. That’s the main thing.”

To Frank Tallman, that was the main thing—the only thing. The problem was time. He had contracted with 20th Century Fox to do the aerial work for “The Flight of the Phoenix.” Otto Timm, the famed aviation designer, had already designed the makeshift plane the World War II US Air Force survivors built to escape from the Libyan Desert, and the movie crew was waiting—for Frank. The following Sunday, I was talking with Paul Mantz in his office:

Paul: “Well, Cliff, it looks like the old man will have to do the job.”

Cliff: “Why?”

Paul: “Well, you know movie people. They always want it yesterday! They’ve been callin’ like crazy.”

Cliff: “Oh hell. Let ’em call a few more days. They can wait, can’t they?”

Paul: “They say no. That means I’ve got to say yes.”

Cliff: “But you don’t want to fry in that Arizona desert sun, Paul. It’s 110 degrees in the shade, and there ain’t no shade. Besides, you’ve got three young pilots who are dying to do the job.”

(Note: I was concerned because Paul was getting on and certainly didn’t need to prove anything. He had done it all!)

Paul: “That’s the trouble. They’re young and restless—and the airplane ain’t a real airplane. It’s made of parts from a wrecked bomber. And that sand ain’t no smooth runway. No. Looks like I’ll have to go to Arizona.”

(Note: I wasn’t about to argue with one of the world’s great stunt pilots and watched Paul begin to pack.)

Cliff’s Notes:

As a youngster in La Jolla’s Granada Theatre, I couldn’t wait to see the Saturday movie matinee. Not the acting, but the flying. The serials lasted 20 minutes and continued for 10 or 12 weeks. Each segment ended as a “Cliff Hanger” (pardon the pun) to be continued the following Saturday. Frustrating, but fascinating. So, kind patient readers, we will continue this month’s column next month. Forgive me. Mea culpa. Cliff

Academy Award and Emmy Award winning screen star Cliff Robertson has owned and flown a wide array of aircraft, including a Spitfire MK IX, a Messerschmitt ME-108, a French aerobatic Stampe SV4 biplane, a Grob Astir glider (in which he still holds a distance record) and a Beech Baron 58. A holder of single, multi, instrument and commercial licenses, as well as balloon, the pilot of many thousands of hours has accumulated many aviation awards, including EAA’s highest Eagle award and the AOPA Sharples award. He was recently inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, and the American Veteran Association has honored Cliff as Veteran of the Year. His columns will appear in his soon-to-be-published book. For information about Cliff, visit [http://www.cliffrobertson.info].