By S. Clayton Moore,

Humble beginnings

Although he grew up to be a gifted public speaker, McGovern was painfully shy as a child. He nearly flunked first grade, because he was too embarrassed to speak in class. Despite his bashfulness, he had good friends and enjoyed an idyllic childhood, complete with a tree house, a rubber tire on a swing, and visits to the annual Corn Festival in Mitchell.

He experienced a dramatic turning point in the tenth grade, when his English teacher, Rose Hofner, singled him out for the school’s debate team. In 1940, he enrolled at Dakota Wesleyan University, where he was twice elected class president and won the state’s oratory contest. His speech, “My Brother’s Keeper,” expressed his belief in one’s responsibility to mankind.

At the university, McGovern first learned to fly, as a member of the U.S. Government’s Civilian Pilot Training Program. A friend, Norman Ray, from Custer, S.D, talked him into joining the pilot training program’s first class of 10 students. He took eight hours of instruction in a government-supplied single-engine Aeronca, before soloing on a windy day, circling over the Corn Palace, the Wesleyan campus and Lake Mitchell.

“Frankly, I was scared to death on that first solo flight,” McGovern remembered. “But when I walked away from it, I had an enormous feeling of satisfaction that I had taken the thing off the ground and landed it without tearing the wings off.”

In college, he fell in love with Eleanor Stegeberg, a smart, beautiful girl from Woonsocket, S.D. Earlier, Stegeberg had beaten McGovern in a formal high school debate. He married her in 1943; on Halloween of 2005, they celebrated their 62nd wedding anniversary.

Into the Wild Blue Yonder

Eleanor McGovern pins silver pilot wings on her husband, newly-commissioned Second Lt. George McGovern, on April 15, 1944, at Pampa Army Air Field, Texas.

George McGovern’s war experiences are detailed in historian Stephen Ambrose’s gripping book, “The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s over Germany.”

In the fall of 1941, McGovern first saw B-24 bombers landing at the auxiliary landing field at Mitchell Airport. He couldn’t have imagined that he would soon be in command of one.

“Hitler was already on the march, but it wasn’t until Pearl Harbor that I realized it was a really serious war,” McGovern said.

In a matter of days following the attack, McGovern enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps, and was sworn in at Fort Snelling, Minn. Capitalizing on his limited aviation training, the Army trained McGovern as a pilot. He flew PT-19s at Muskogee, Okla.; BT-13s at Coffeyville, Kan.; got his twin engine training in Pampa, Texas, on the AT-17 and AT-9; and finally went to Liberal, Kan. to fly the B-24 Liberator in 1944.

Sitting alone in the barracks, McGovern nervously waited to meet his instructor. He couldn’t have been more surprised. In walked Norman Ray, the friend that talked him into flying in the first place.

“It really was a shock,” McGovern laughed. “Norman Ray had been gone a year and a half; by then, he was an instructor for B-24 bombers. He was terrific. I had really excellent instruction.”

Not that the B-24 was an easy plane to fly. An enormous, lumbering bomber, the B-24 Liberator had a wingspan of 110 feet and weighed over 60,000 pounds with a full bomb load. It was an ideal aircraft for the air war in Europe. With a maximum ceiling of 32,000 feet and a range of 2,850 miles, it was a lethal, if somewhat unstable, weapon.

“Learning how to fly the B-24 was the toughest part of the training,” McGovern said. “It was a difficult airplane to fly, physically, because in the early part of the war, they didn’t have hydraulic controls. If you can imagine driving a Mack truck without any power steering or power brakes, that’s about what it was like at the controls. It was the biggest bomber we had at the time.”

Thirty-Five missions

In September 1944, McGovern was posted to the 741st Squadron, 455th Bomb Group, based at San Giovanni Field in Cerignola, Italy. His mission priority was to knock out Hitler’s oil refineries in Germany, Austria, Poland and Czechoslovakia. During his 35 missions, McGovern dropped ordinance on all these countries, including bombing runs at heavily defended cities like Munich, Germany, and Linz, Austria.

The boys of his crew decided that since he was the only married man on the ship, their B-24 should be named the Dakota Queen, as a tribute to Eleanor. From that moment on, McGovern called any plane he flew by that name.

It was physically demanding work, holding the big bomber steady for up to 12 hours, sweating out the gas supply and hoping the Luftwaffe didn’t fill the plane full of holes.

“I remember All American football players from Big 10 schools who literally had to be lifted out of the cockpit after a mission,” McGovern said. “We had big sheepskin-lined leather suits, boots, helmets, an oxygen mask and goggles, so you were completely encased. Then you had the fatigue of 10 hours of flying.”

George McGovern’s heroism during World War II is detailed in “The Wild Blue,” written by “Band of Brothers” historian and author, Stephen Ambrose.

To say the missions were dangerous is a dramatic understatement. “I didn’t realize until I read Stephen Ambrose’s book that half of the bombers and crews that flew in World War II never made it through the war,” McGovern said. “That was double the casualty rate of infantry officers. That’s a grim fact.”

On Dec. 17, 1944, he had started a combat flight towards Odental, Germany, when the right-hand wheel blew. He knew that ridding the plane of gas and bombs would make for a safer landing, but he completed the mission. Three days later, he was on a mission to bomb a factory at Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, when a prop flamed out on him. Using every ounce of his piloting skill, McGovern recovered and guided the Dakota Queen to a forced landing on a fighter strip on the isle of Vis, a mountainous island off the coast of what is now Croatia. He managed to land, tires and brakes smoking and screaming all the way down the runway.

“They had a 2,200-foot runway staffed with British Spitfires,” he recalled. “They could land on a runway that size, but it’s not smart to try to land a four-engine bomber on it. But we got it done and that’s why I got the Distinguished Flying Cross.”

McGovern’s last mission might have been his worst. On April 25, 1945, the Dakota Queen joined all four squadrons of the 455th, in an air assault on heavily defended Linz, Austria—Adolf Hitler’s hometown. The flak was intense, riddling shrapnel into the Dakota Queen and its crew.

“We had 110 holes in the fuselage from antiaircraft fire,” McGovern said. “Why it hit just one guy (Sgt. William “Tex” Ashlock), I’ll never know. You can’t put a hundred holes through an airplane without wondering how it didn’t hit more people, or hit the gas tanks and blow us up.”

The Dakota Queen’s hydraulics were ruined, nearly crippling it. McGovern had no control over the flaps or the ailerons, the brakes were shot, and the crew had to hand crank the landing gear down.

“Everything was well paralyzed when we hit the ground,” McGovern remembered. “We had a parachute on either side of the plane, tied to a stanchion. We threw those out the waist windows to help slow the plane down since we didn’t have any brakes. We ran the whole length of the runway; at the end, the plane went into a little ditch and we heard the tail slap down. I had one waist gunner who was badly hit over the target; another guy had a bad leg sprain when we hit the ground.”

War’s end

With that last mission, the war was nearly over for George McGovern. After 35 missions, each crewmember was eligible to go home. Ironically, the war ended just weeks later, when Victory in Europe—now known as VE Day—was declared on May 8, 1945.

McGovern’s most vibrant memory of the war is of a terrible, unsuccessful mission. On March 14, 1945, the Dakota Queen was badly hit during a mission over Austria, and one of the 500-pound bombs jammed in the rack. Knowing that landing the heavy bomber with an armed bomb loose in the rack could be fatal, the crew jimmied it loose. It fell into the middle of a small cluster of farmhouses.

“I looked at my watch,” McGovern recalled. “It was noon, on a beautiful, sunshiny day. I thought, ‘That’s terrible. We probably killed someone’s young family, having lunch, thinking they were safely out of the war zone.'”

He felt even worse after he landed, when he received a telegram informing him that Eleanor had given birth to their first child, Ann. For years afterward, he felt regret about the accidental bombing. In 1985, when he was lecturing at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, a television reporter asked if he had any regrets about bombing beautiful cities like Vienna, Salzburg or Innsbruck.

“The shorthand answer is no,” he replied. “I thought Hitler was an inhuman monster, so I’m pleased that I played some small part in breaking up his war machine. But there was one mission I regret.”

He told the story of the failed bombing mission over Innsbruck. That night an elderly Austrian farmer called the television station.

“Tell the American senator that it was my farm,” he said. “We saw this low bomber coming, where all the others that had come over earlier were way up above. I got my wife and three daughters out of the house and we hid in the ditch, and no one was hurt. You can tell him that I despised Adolf Hitler, even though my government threw in with him.”

McGovern breathed a sigh of relief, letting go of a worry that had haunted him for 40 years.

“After all those years, I got redemption,” he said.

In a coda far different from his war experience, McGovern volunteered for a few last missions at the request of General Nathan Twining, commander of the 15th Air Force. His task was to fly the government’s war supplies of food, clothing and medications to drops in northern Europe, where civilians were suffering in the war’s aftermath.

“As much as I hated to delay going home, I’ve always been glad I did that,” he said. “In some cases, we were dropping food and clothing to people we’d been bombing just a few days before. I’ve always been glad that the war ended for me on that humanitarian note.”

A political awakening

McGovern finally graduated from Dakota Wesleyan University in 1946. He attended Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary in Evanston, Ill. for a year before enrolling at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., where he earned a PhD in American history and government.

In the early 1950s, he turned his attention to politics. His parents were lifelong Republicans, but McGovern found his developing ideas had grown beyond his parent’s conservative ideology. He volunteered for Adlai Stevenson’s campaign and then ran as a Democrat for the House of Representatives in 1956, winning South Dakota’s seat in the 85th and 86th Congressional sessions.

“I really wanted to change things, both there at home in the United States and in our foreign policy,” McGovern explained. “I felt the United States ought to be doing things like providing universal health care for all Americans. I thought we ought to feed the hungry with our farm surplus. I thought we needed to take better care of the trees and the soil and the waterways, and that we needed a price support system to keep farmers from going under. That’s why I ran.”

After serving in the House, he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1960, losing to Republican incumbent Karl Mundt. The loss became an opportunity when he was appointed by President Kennedy to be the first director of the Food for Peace program, which used American surplus crops to help hungry people in other nations.

“I consider myself fortunate in that I became quite close to all the Kennedys,” he said. “They’re one of the most remarkable families on the face of the earth. All of them could have given themselves up to being international playboys. They were all rich, they all inherited ample funding and instead, they all worked their heads off in public service.”

McGovern was elected to the Senate in 1962, serving the first of three subsequent terms. He stayed loyal to his interests in fighting hunger and supporting American farmers, with key positions on Senate committees on agriculture, nutrition, forestry and foreign relations.

He supported the 1968 presidential campaign of his friend Robert Kennedy. Just minutes before an assassin shot and killed Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, Kennedy was on the phone with McGovern, who was giving him the South Dakota election returns.

“He was a dedicated man,” McGovern said. “I never forgot the image of Bobby out there in the wind and the cold and the rain, trying to carry on the fight, to get us out of Vietnam, and to get poor people out of the ditch.”

Many of Kennedy’s supporters threw themselves behind George McGovern in the run-up to the 1968 election, but the presidential nomination would ultimately go to Hubert Humphrey. The real battle came in 1972, as McGovern ran against the powerful incumbent, President Richard M. Nixon.

The campaign trail

McGovern recently had the opportunity to revisit his historic presidential campaign, through a new documentary film directed by Stephen Vittoria, “One Bright Shining Moment: The Forgotten Summer of George McGovern.”

“It was a pleasure for me to hear some of those voices again,” McGovern said. “I think it’s a brilliant film.”

Featuring interviews with central figures, including the candidate and his campaign manager, Gary Hart, as well as well-known supporters like Warren Beatty and Gloria Steinem, the film chronicles McGovern’s dramatic 1972 presidential run.

Most scholars say the election that year was won and lost on law and order, and the Vietnam War. McGovern’s platform called for an immediate end to hostilities in Vietnam, a position he stands by today.

“I just couldn’t bear sending those young guys over there to wade around in that jungle looking for people who were no threat to us,” McGovern said. “They never wanted anything except for our government to recognize their rebellion. I guess we forgot that we were born in a rebellion.”

Other tenets of his platform included a significant reduction in defense spending, support of the Equal Rights Amendment, and amnesty for draft evaders. His acceptance speech for the Democratic nomination was called “Come Home, America,” a slogan soon adopted by his campaign.

His campaign was supported by a host of high-profile endorsements, such as that of “McCloud” actor Dennis Weaver, whose memorial services McGovern attended in March.

“He was a remarkable man,” McGovern said of the late actor. “I just thought he wanted to make an endorsement, but he joined the campaign and traveled with me all over the country.”

Convinced that McGovern would “whip Nixon,” Weaver presided over the campaign’s last rally in Long Beach, Calif., where more than 100,000 supporters rallied behind his chosen candidate.

The senator rallies “McGovern’s Army,” with a speech in Syracuse, N.Y., Halloween 1972. When interrupted by church bells, McGovern exclaimed, “The bells are tolling for Richard Nixon!”

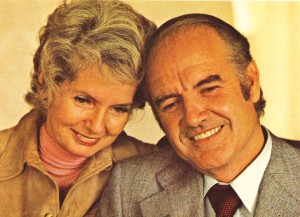

The 1972 campaign, like all McGovern’s campaigns, was encouraged by his enthusiastic and loyal wife. Eleanor set a new precedent by campaigning independently of her husband, speaking at rallies throughout the country and appearing as a guest on television and radio programs. Her efforts changed the way Americans view spouses of politicians.

Another enthusiastic supporter was Hunter S. Thompson, the late “gonzo journalist” and Rolling Stone writer. Calling McGovern “the best of a lousy lot,” he chronicled the campaign in his popular, quasi-fictional book, “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail 1972.” It, along with Timothy Crouse’s pivotal campaign book, “The Boys on the Bus,” paints an engrossing portrait of McGovern’s grassroots campaign. McGovern’s political director, Frank Mankiewicz, called Thompson’s book “the least accurate and most truthful” of the campaign books. McGovern, who remained friends with Thompson until his death in 2005, agrees.

“Hunter started following me very early on, when I was just a voice in the wilderness,” McGovern recalled. “He clung to me pretty tightly and I got a kick out of him. A lot of people thought he was frivolous, but I never did. I thought behind that gonzo exterior was a deadly serious, caring, idealistic man, and I still do.”

Just days before the 1972 election, George and Eleanor McGovern wave to the crowd from the steps of their campaign plane, the Dakota Queen.

According to some polls, McGovern came within five percentage points of President Nixon in popularity, but his campaign was soon derailed. He ran against enormous opposition by the Republican Party, and was viewed by some, even within the Democratic establishment, as borderline radical. His campaign also suffered from widespread criticism of Thomas Eagleton, McGovern’s choice for vice-presidential candidate. Sargent Shriver later replaced Eagleton, who revealed he’d been hospitalized several times for nervous exhaustion.

Today, McGovern is uncertain if a grassroots campaign could be as successful as his own.

“Television is such a powerful instrument,” he observed. “Nixon spent three or four hundred million dollars running against me, even though he had no competition in the primary. With that kind of money, you can buy an enormous amount of television time. I’m not sure that a strictly grassroots campaign, depending as heavily as I did on volunteers, could prevail in today’s media market, but it might.”

President Nixon famously predicted that he would win the election because of the “silent majority” of voters who keep their politics to themselves. He won by a landslide victory of 61 to 38 percent, winning a majority vote in 49 states. Only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia went to McGovern. Within two years of the election, Nixon was forced to resign due to the Watergate scandal.

Learning from defeat

More than 30 years later, McGovern wonders if President Nixon would be remembered with more compassion if he had lost his bid for reelection.

“From Nixon’s standpoint, he would’ve been much better off,” he said. “He would’ve gone down in history as the guy who opened the door to China and achieved détente with the Soviet Union. If he hadn’t been caught up in Watergate, he would’ve gone down as a pretty fair president. Americans aren’t a vindictive people. They want to believe the president.”

Despite the “dirty tricks” of the Nixon campaign, McGovern feels no animosity against the late president, and spoke cordially of President Nixon at his funeral in 1994.

“I never said to the American people, ‘I told you so,'” McGovern said. “I think Hunter wanted to rub his nose in the dirt. I don’t carry grudges and I’ll tell you why. It takes too much energy to be mad at somebody. Then you have to remember who you’re mad at; pretty soon, you wonder what the reason was. It’s OK to be mad for a while, but then you have to forget about it and go on with your life.”

Despite the outcome of the election, McGovern doesn’t regret his controversial outlook on the war in Vietnam or any of the other contentious stands he’s taken over the years.

“I believed everything I said in that campaign,” he said. “That doesn’t always mean I’m right, but I said what I thought was right. If I had one piece of advice to give to my fellow politicians and fellow Americans, I’d say, ‘Never say anything that, down inside, you think is wrong. Say what you think is right, even though you might get your ears boxed after saying it.’ I think personal and national freedom are dependent on knowing the truth.”

He also takes some comfort in knowing he played a significant part in ending the Vietnam War.

“Once we got almost 30 million votes, the war was dead,” he said. “When an anti-war candidate got nominated for president by the oldest party in American history, everybody knew it had to end, so I’m glad I ran.”

While he’s often asked about the election, he doesn’t dwell on it.

“I learned something else,” he explained. “I’ve learned that sometimes, disappointment or a defeat can teach you as much or more than a victory can. Nixon was a great landslide winner in 1972, but I’ve never had any desire to trade places with him.”

The global family

Following the exhausting presidential campaign, McGovern returned to South Dakota, and was re-elected to the Senate in 1974. In the wake of Ronald Reagan’s popular campaign, Republican candidates swept Congress in 1980, and South Dakota’s Republican Representative James Abdnor defeated McGovern in his final Senate race.

In 1984, McGovern made another run for the presidency. The crowded field included Walter Mondale, astronaut John Glenn and Gary Hart. He withdrew soon after the New Hampshire primary.

McGovern’s subsequent career as an activist on global issues was initiated in 1976, when President Ford named him a United Nations delegate to the General Assembly. His work with the United Nations continued when President Jimmy Carter appointed him a U.N. delegate for the Special Session on Disarmament. He still advocates the U.N.’s mission, often declaring that the United States needs to join the “global family.”

Teaching has always come easy to the once-shy McGovern. He spent much of the 1980s as a visiting professor at numerous institutions around the world, including Columbia University, Northwestern, Cornell and the University of Berlin.

The McGoverns suffered a personal blow in 1994, with the death of their daughter, Teresa, known to friends and family as “Terry.” Her lifelong battle with alcoholism led to her death, after many attempts at rehabilitation. McGovern recounted her story in a best-selling book, “Terry: My Daughter’s Life-and-Death Struggle with Alcoholism,” and established a recovery center in her name, in Madison, Wis.

Through much of the 1990s, he led the Middle East Policy Council, a nonprofit think tank that examines policy issues in the Middle East. Not surprisingly, he doesn’t think much of current U.S. foreign policy.

“I knew this war was a mistake,” he said of the ongoing Iraq war. “We have to quit getting into these complicated, difficult civil and revolutionary conflicts and try to exercise some restraint as to where we send our young men and women. This is probably the best army we’ve ever sent overseas, and we’re giving them a hopeless task.”

McGovern also calls for a return of credibility in American politics—from both parties.

“People have got to quit lying in politics and tell the truth,” he said. “You know, we’ve had nothing but lies too much of the time.”

Fighting hunger

On Aug. 9, 2000, George McGovern was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton, who once campaigned on McGovern’s behalf, in Texas. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the nation’s highest civilian award.

“George McGovern is one of the greatest humanitarians of our time,” Clinton said at that time. “He still imparts to us the power and courage of his convictions.”

Clinton also appointed him as U.S. ambassador to the U.N. Food and Agricultural Agencies in Rome from 1998 to 2001, where McGovern continued his lifelong call to action against worldwide hunger.

Inspired by the suffering he saw in Italy following World War II, McGovern wrote extensively about the subject in his book, “The Third Freedom: Ending Hunger In Our Time.” His new book, “Ending Hunger Now: A Challenge to Persons of Faith,” was coauthored by former Senator Bob Dole and contains a forward by Clinton.

“I’ve been the point guy on global hunger for about 50 years now,” he said. “We’re trying to provide, through the United Nations— with the United States in the lead—a good, nutritious lunch every day, for every hungry school child in the world. That’s 300 million kids, and it’s a solvable problem.”

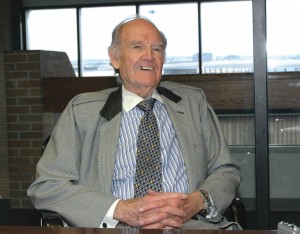

His comprehensive plan advocates United Nations food reserves, the encouragement of scientific agriculture, a universal school lunch program, and the expansion of America’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program, to reach low-income women, infants and children worldwide. He says he plans to live to 100 or beyond, so he can see the end of hunger in his lifetime.

“I want to feed those 300 million, and Bob Dole wants to see it done, too,” he said. “We got $300 million from Bill Clinton just before he left the White House, and $200 million out of President Bush. With that money, we have pilot school lunch programs going in 38 poor countries around the world. Now we have to get other countries to match us.”

In his view, it’s the most important issue facing the world today, and he truly believes in the power of the United Nations’ efforts.

“It will reduce disease,” he explains. “It will improve the health of children everywhere. I think it will transform life on this planet.”

The McGovern legacy

While he remains a symbol of the political left, he also stays involved in contemporary political issues through his writing, speeches and bipartisan efforts, such as his work with Senator Dole.

In 2001, he published “The Essential America,” a sharp defense of liberal ideals, as the catalyst for the forward movement of the country. He lectures up to four times a week and maintains close ties with other movers and shakers in Washington.

McGovern still goes where he feels he can help, keeping his finger on the pulse of the country. On Sept. 4, 2005, he flew to the Houston Astrodome, to show his support for the victims of Hurricane Katrina.

Eleanor McGovern, pictured with Senator McGovern, independently campaigned for her husband, and transformed the way the public views the spouses of candidates.

He also spends time with his wife, who now stays closer to home in South Dakota, as well as his children—Ann, Susan, Steven and Mary—his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. To honor George and Eleanor McGovern, a library/archive has been established in their name at Dakota Wesleyan University. It will be dedicated in October 2006.

A war hero and a man of conscience, George McGovern maintains his compassion for the common man, his faith in the central decency and fairness of humanity, and his great belief in the country he defends to this day.

“I still think this is the greatest country on Earth,” he said. “It must be great, because we make these horrendous mistakes, but we bounce back. I saw this country survive the Great Depression through the 1920s and 1930s, when I was growing up. I saw us not only survive, but win World War II, when we had to come back from almost nothing. I see this country slowly awakening to the environmental threat and doing something about it. It must be a great place.”

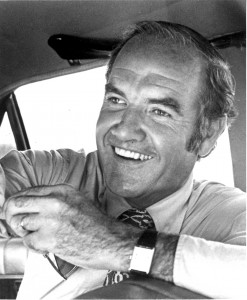

Senator McGovern shares his memories of World War II, his campaign against President Nixon, and his 50 years in American politics, during an interview with Clayton Moore.

For more information on George and Eleanor McGovern, visit the George and Eleanor McGovern Library and Center for Public Service at Dakota Wesleyan University at [http://www.mcgovernlibrary.com].