By Di Freeze

Although Dan Hanchette, vice president of Viper Aircraft Corporation, used to get sick in airplanes, he learned to like flying because he enjoyed spending time with his brother.

Dan Hanchette wasn’t one of those boys–like his brother Scott–who developed a mad passion for aviation and longed desperately for the day he could fly, or be involved in that field somehow.

“I was the kind of kid who used to get sick in airplanes, but because I enjoyed spending time with my brother, I learned to like airplanes and the business,” said the vice president of Viper Aircraft Corporation.

Eventually, he even took some lessons, but he’s still a student pilot.

“I’ve flown a number of airplanes,” he said. “I’ll jump in an airplane with Scott, and he’ll have his nose in a map and say, ‘All right, Dan, she’s yours.’ I do plan on getting the rest of my license. It’s just that right now things have been busy; I haven’t had the chance to get it done.”

The 41-year-old resident of Richland, Wash., jokingly describes the Viper Aircraft president’s interest in aviation as his “sickness.” Scott Hanchette’s disease began when their father, George Hanchette, who wasn’t a pilot but always had an interest in aviation, began taking the toddlers regularly to an airport in Phoenix. There, an elderly pilot named Clarence took young Scott Hanchette under his wing.

“Ever since he was just a little kid, he was always drawing pictures of airplanes,” said his brother.

The sickness got worse after the family moved to the Denver area, and George Hanchette became friends with a Continental Airlines employee.

“They used to take us into the hangar and let us sit in the front seat of the DC-9s,” Dan recalled.

After the family moved to Spokane, the brothers began preparing for their destiny in manufacturing by going into business together.

“We made sawdust fire starters,” Scott Hanchette said. “We’d sell them by the dozen.”

He and their father manufactured the product. Then, after loading the fire starters into a wheelbarrow, Dan, three years Scott’s junior, would take them door to door. He’d hand out sample packages and business cards, and enlighten the customer with his well-prepared speech, including extensive “test data” showing how their product burned longer and was better than others. Later, he’d call and politely ask how many fire starters the person wanted, and when would be the best time to deliver them.

“I always did the assumptive close,” he said. “We did well. I had the trickest BMX bicycle on the block, and I paid for every bit of it.”

The path from that bike to a far cooler and faster form of transportation was one that the brothers, for the most part, traveled together. But Scott did take some solo jobs, including working for Felts Field Aviation as a line boy, in Spokane, and in Athol, Idaho, at Henley Aerodrome.

He started taking flying lessons at Henley when he was 14 and a half, before switching over to Felts Field to continue lessons there. Following that, he worked at Aero Transit Airlines in Spokane.

“That was a cargo and charter type flight,” he said. “We had three or four DC-3s.”

He worked his way into a job through the back door, doing their printing that he used to do in school, and moved up to cargo director.

The family moved to the Tri-Cities in 1980, two years after Scott Hanchette graduated from high school. There, Dan started a mail order business with 60 dollars borrowed from his father to run the company’s first ad. The brothers sold information related to the General Service Administration regarding public and sealed auctions, and bids on confiscated cars, IRS seized properties, etc.

“People didn’t know that GSA even existed or that they could participate in those auctions,” Dan said. “We sold them information for $9.95, plus $2 shipping and handling. It supported us for a few years.”

After Scott made a profit on a BD-5 kit plane he sold, he came up with the idea of forming an aircraft brokerage. They began Titan Air in 1982.

“We’d consign airplanes and park them at the airport (Vista). We operated the business out of an apartment complex,” he said. “We specialized in finding aircraft, buying them and selling them to other aircraft brokers, to then sell them retail in larger markets.”

They did well, selling 30 to 40 airplanes a year through 1986, until interest rates went up to 20 percent. Although they still dabbled in brokering, they next ran a franchise for Sunshine Polishing for about seven years.

Although their business was classified as an automotive appearance center, the Hanchettes became well known for the immaculate detailing they did on cars of all types, boats and yachts, aircraft and even motor homes. The brothers went out of their way to make sure their center was different than others.

“We made it elite,” Dan said. “Our people wore uniforms and carried check-off boards, because the cars went through point inspections.”

Although his brother was still “sick with airplanes,” Dan’s involvement in bodybuilding led them to acquire a franchise for Gold’s Gym, the largest international gym franchise in the country. They broke ground in 1993, and sold Sunshine Polishing to a friend.

They received Gold’s Gym’s Rookie of the Year award in late 1993.

“Five hundred clubs had opened up, and ours sold the most memberships,” he said. “We had 700 pre-sold memberships before we ever opened the door.”

The Gold’s Gym and Aerobic Center included childcare, an espresso bar and supplement sales, a tanning salon and a pro shop. Dan tackled sales and marketing, including launching innovative giveaway campaigns. Scott oversaw the customer service end, as well as bill collecting and maintenance. Dan’s wife Amber was the business manager.

Scott said the gym business was probably their most difficult endeavor.

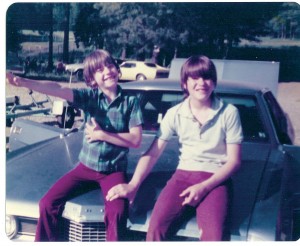

L to R: Dan and Scott Hanchette have been in business together since they were children and began manufacturing fire starters.

“You’re open 17 hours a day, 364 days a year, and you have 3,000 to 3,500 little ‘kids’ constantly complaining,” he said.

Besides listening to complaints about everything from what music played in the gym to the price of membership, another problem was that the membership constantly fluctuated.

“In a metro area, you don’t go through the fluctuation we do here, in a 150,000 population area,” Scott said. “If Hanford dumped 1,000 or 2,000 people, 300 members would cut their membership in a month.”

Although the gym was “fairly successful,” Scott was particularly happy when they got an offer for the gym in 1997. One reason was that his heart was more into an aircraft the brothers were designing.

“During the day, we were working the gym,” he said. “At night, we were working on the Viperfan, our propeller-driven pusher airplane.”

After George Hanchette was diagnosed with cancer, they took the offer from a racquet club in town, deciding to sell the gym so they could pursue designing their aircraft full time, and have the money to finance it.

The Viperfan

Dan Hanchette recalls that his brother started designing the Viperfan back in the mid-1980s.

“It was just on paper,” he said. “At that time, composites weren’t mainstream. Prepreg composites were very expensive and only used by aerospace companies, so the time just wasn’t right. Scott continued for a number of years just drawing pictures of this aircraft. It got more and more intricate in the design.”

Although Scott Hanchette began the design of their aircraft, his brother has contributed a lot of input.

“I’ll come up with a sub-assembly idea or something, but I see in one dimension,” he said. “Scott sees in three dimensions. I can tell him, ‘I have this idea for this piece or this part on the airplane,’ and he’ll say, ‘Tell me more about it.’ I’ll try to draw it, but I can only draw it one way, and it really doesn’t explain what it is. He’ll start drawing it, and I’ll say, ‘That’s it! No, get rid of that. Yeah!’ He can draw exactly what’s in my mind.”

In 1995, years after those first drawings began, the Hanchettes visited EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, where they met Reno-based engineer Mark Bettosini.

“Mark took a look at these pictures and asked Scott what college he graduated from,” recalled Dan Hanchette. “When Scott told him he hadn’t been to college, Mark said, ‘This is good. This interests me.’ He said, ‘Would you mind if I take them home after Oshkosh and just review them and look at them?'”

A week later, the AirBoss Aerospace cofounder called and said, “How do I get involved in this?”

“That was really the kick that told us, ‘Maybe there’s something here,'” Dan said.

In 1996, they started doing the tooling.

“We went straight to production,” Scott said.

The brothers formed Viper Aircraft Corporation in Pasco, Wash., where Scott lived, and hired Composites Unlimited, a composite manufacturing company in Scappoose, Ore., to make their molds, tooling and parts (beginning with the wings and horizontal stabilizer). The company worked off faxed drawings from Bettosini.

“Scott and I had no composite building experience,” Dan said. “We didn’t start out on a Lancair or anything like that. We just jumped right in and started building a jet.”

At that time, the Hanchettes also housed two other aircraft in the hangar at Tri-Cities Airport (PSC), including a CASA Jet Scott was rebuilding. In time, they rented out a corner of an old WWII Quonset hut on the airport. There, they began building the fuselage for the first prototype.

“Composites Unlimited would send us the parts, and we’d assemble them,” Dan said.

It took the brothers a little over three and a half years to go from paper to flying the prototype.

“We got the fuselage shell nearly complete, and we started designing and engineering what it was going to take to have this carbon fiber drive shaft, a six-cylinder Continental engine, a five-blade prop–all of these complex moving parts–with a propeller at the wrong end of the airplane,” he said.

Everything seemed like it would turn out perfectly, but then they started looking at the money it was taking for that type of power plant.

“We also started thinking, ‘What if there are any harmonics, vibrations or anything in the drive system that translate through? We could be chasing little noises that cost thousands of dollars,'” Scott recalled. “I pulled Danny off to the side and said, ‘You know, if we have problems with this, it’s not going to be a good thing.'”

His younger sibling had an immediate solution.

“We can have a jet engine in this thing in about a week,” he said. “It would be a lot easier.”

The Viperjet

Scott Hanchette was soon on the phone with a friend that had imported some Fouga jets and a surplus of Turbomeca engines.

“He said, ‘What are the chances of getting one of these engines down here so we can take some measurements,'” recalled his brother.

When they told Bettosini about the jet idea, he was thrilled.

Dan Hanchette said the Viperjet MkII “outperforms almost every surplus military jet you can buy on the market today.”

“We had an engine here a week later,” Dan Hanchette said. “We started doing some rough mockup work, getting it fitted and dialed in; everything fit fine. We started welding up mounts. Within a few weeks we had it, for the most part, installed, as far as aligned right, and where it’s going to sit. We had a tailpipe made. Then we started hooking up the electrical, the fuel lines and things, and it turned into the Viperjet.”

The Viperjet flew in October 1999, with test pilot Len Fox at the controls.

“He was referred to us by Composites Unlimited,” Dan said. “Len’s an ex-Navy adversary instructor. He’s also a competitive aerobatic pilot. He’s very well educated, with a very strong aviation background. The neat thing about Len is he’s a test pilot that knows a lot about aerodynamics.”

They took a lot of Fox’s suggestions to heart when it came to the Viperjet.

“He’s been instrumental in assisting us on some ideas, which has been a real help,” he said. “When he flew it in October 1999, he said the Viperjet handled very well, and that it exhibited no bad handling characteristics. He said it was really a fine flying airplane.”

But when they discovered that Turbomecas “aren’t the most fuel-efficient engines,” they started looking for other power plants.

“The General Electric T58 was suggested to us,” he recalled. “It’s really a helicopter engine. We modified it by removing the power turbine and putting a tailpipe on it. The engine then produced about 750 pounds of thrust.”

They flew the aircraft for a couple of years that way, but it still lacked the power they desired.

“We really wanted it to perform as well as it looked,” he said.

After going back to the drawing board, they started thinking about the J85, GE’s military variant of the CJ610.

“They’re accessible, and they’re affordable, and they’re one of the most reliable turbojet engines ever built,” he said. “That’s what we decided, and it changed the whole airplane. Because of the extra thrust–four times the power–we had almost 3,000 pounds (2,850) of thrust instead of 700.”

But that meant the aircraft needed to carry more fuel.

“We also needed to have new landing gear, because your gross weights were heavier,” he said.

Although they already had aircraft sold, they basically started over.

“We had to tear this perfectly good prototype down, take it back to zero and rebuild it,” Scott Hanchette said.

Although they kept the basic shape of the fuselage, parts including the wings, tail, instrument panel, landing gear, engine bays, control surfaces and flaps were all changed out to accommodate what would be called the Viperjet MkII.

“We started the tooling on this new airplane, which really shared most of the same fuselage parts,” Dan said. “As soon as we could get the parts, we started building. We left a couple of the pieces, like the canopy frame and the windscreen, part of the midsection of the azircraft, but with all the new parts that were tooled up, we replaced everything with all the new pre-molded MkII parts. We upgraded all of our customers with those parts at no extra charge.”

At that time, they also decided to make 95 percent of the aircraft carbon fiber. Although starting over cost them more than they had planned, he said it wasn’t as bad as it could’ve been.

“It has been expensive, but it definitely hasn’t been as expensive as it would’ve been for other people, because Scott and I are very involved; we’re hands-on,” he said. “We didn’t just hire a bunch of guys to come in here, and say, ‘OK, start building.’ We know every part of this airplane.”

They also have the help of one extraordinary employee, Eddie Robbins.

“He’s been with us during most of the rebuild of the new MkII,” he said. “He started out as the painter and turned into one of the best workers you could ask for. He’s a real team player.”

The Viperjet MkII

The Viperjet MkII reincarnation was completed in May 2005. At that point the Hanchettes brought Fox back to start the test-flight syllabus.

On June 12, 2005, at 2:15 p.m., the fully aerobatic, tandem-seat, jet-propelled Viperjet MkII lifted off runway 21 right at PSC. Fox took the jet for a successful 25-minute debut flight. Recently, during advanced flight-testing, the jet exceeded its projected true airspeed of 325 knots at 25,000 feet.

“We’ve had it at 561 mph, with quite a bit of throttle left,” Dan Hanchette said.

The jet has a 77-knot stall speed, and the initial rate of climb is 10,000 feet per minute. Range is 800 miles without tip tanks, and 1,000 to 1,100 with tip tanks.

The brothers say the MkII can’t be considered a very light jet in the “certified realm,” but many still look at it as a VLJ.

Scott Hanchette, president of Viper Aircraft Corporation, discovered his love for aviation when his father began taking him and his brother to an airport in Phoenix and an elderly pilot took him under his wing.

“We designed this to be a sport jet–aerobatic–but that’s not who’s buying it,” he said. “Since the events of 9/11, business people are buying this airplane. They’re comparing it to Citation jets and a number of VLJs.”

The main difference between those aircraft and the MkII is that the Viperjet doesn’t come totally completed.

“You need to build on parts of this aircraft or have builder assistance in building parts of this,” he said. “That’s where the equity position comes in. To certify a two-seat jet–ours or somebody else’s–you’re going to spend $100 million more, hence the fact that you need to charge an arm and a leg for it. If we were certified, we’d be kind of like the Javelin–at 2.5 or 3 million bucks. That’s not where we feel our market is.”

For various reasons, the Hanchettes aren’t concerned that the MkII isn’t certified.

“Our jet is engineered by a licensed engineering firm,” Dan said. “The parts are manufactured by a company that also manufactures certified parts. We meet or exceed FAR Part 23 regulations.”

Although some pilots who’ve taken notice of the MkII, including at least one celebrity pilot, could easily buy “any” aircraft they choose, Dan Hanchette said this aircraft is a godsend for the “average guy” who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford to own and fly their own two-place jet.

“If you take a look at a brand new Viperjet, you’re going to have between $450,000 and $550,000 into this airplane, turnkey, to where it’s completely built out,” he said. “Compare that to anything in general aviation. If you look at the Columbia 400, which is a certified four-place, that’s $539,000, and you’re 220 knots, compared to us at 450 knots.”

He said the MkII is “more bang for the buck than anything out there.”

“You get the outrageous performance, the look, the stability, the handling qualities, and everything else that you want in an airplane–and it’s as affordable as buying a Mooney Ovation or something like that,” Scott Hanchette said.

That performance, said his brother, is how you’d expect “a military jet to perform.” In fact, he said the MkII “outperforms almost every surplus military jet you can buy on the market today.”

“The difference in our airplane and a military aircraft is our wing design and our tail design,” Dan said. “You won’t find very many military aircraft that have 77-knot stall speed, yet fly over 500 miles an hour. We have this wide range of performance that makes the Viperjet MkII very unique.”

Since the speed of the MkII compares to that of many business jets, the Hanchettes also believe it’s the ideal jet for corporate flying.

“This is the perfect thing for CEOs and presidents of companies and Fortune 500 corporations who also enjoy flying,” Scott said. “Len and I flew it recently. We’re on the east side of Washington; we flew it over to Scappoose, 30 miles north of Portland, and it took 28 minutes. It’s a four-hour drive. While I was flying, I just thought to myself, ‘This is an awesome corporate way of travel.’ If you need to get to your place, do business, go to another, do business, get back home, this is it.”

Due to its slow stall speed and characteristics, the average Bonanza or Mooney pilot can transition into the Viperjet and fly it very safely.

“It’s really benign,” Dan Hanchette said. “When the Viperjet stalls, it literally almost resembles how a canard stalls. It bobbles. The nose bobbles down, you lose very little altitude, and then it recovers on its own. So, if you have that stick in your lap and you leave it there, don’t even try to recover; just bury it in your lap. The Viperjet will bobble, recover, bobble, recover, losing little, if any, altitude. Len does a lot of stuff for the Columbia 400, the Adam 500 and for Beechcraft. He said, ‘Gentlemen, you have one of the nicest stalling aircraft I’ve ever flown in my life.'”

Scott says the Viperjet “far surpasses how most certified aircraft stall,” while his brother says you can fly the airplane “like a puppy dog or you can let the monster out.”

“It can become a tiger as far as its absolute raw power,” he said.

He said that after noticing the Viperjet’s appearance, pilots next want to know how fast it goes, and after that, if it’s safe.

“We tell them what the stall speed is, and its flight characteristics,” Dan said. “But the best way to convince someone of how great this plane flies is to get them in the seat. Call us; book a demo. Because every person that has flown this jet, getting into it, has believed it was going to take more than they thought.

“They think they have to be these military jet-trained Top Gun pilots. It’s so far from the truth. The turbine engines are easier to fly, and there are fewer systems. You can fly the Viperjet at such slow speeds that when you’re in the flight pattern you’re up there literally flying alongside the Bonanzas and the Mooneys. You’re not blowing right by them; you’re pulling it on back. Most people think something that can fly that slowly isn’t going to have the top-end cruise performance. I think we’ve definitely proven them wrong.”

He said the Viperjet makes a great IFR platform.

“I have a number of customers that plan to fly their aircraft for corporate travel to all different types of places and in different kinds of weather,” he said. “However, there’s a company that can put de-ice on the Viperjet. If you need that for a little bit of extra protection, that’s fine, but usually with the performance of the Viperjet–with its power-to weight-ratio–we can get through layers and different altitudes to where there isn’t bad weather very quickly. Unlike a Bonanza that’s having to go through 10,000 feet to get to 15,000 feet; that 5,000 feet takes them three or four minutes. It takes me 30 seconds, and I bust right through it. It makes a big difference.”

Cost and building

Although some might look at the build process as a negative, some pilots prefer the idea of being able to help build their dream jet. It’s an especially attractive idea if that jet employs cutting edge composite technologies and incorporates the sleek, curvaceous design of the MkII.

Due to its slow stall speed and characteristics, the average Bonanza or Mooney pilot can transition with ease into the Viperjet MkII and fly it very safely.

Viper Aircraft has sold 21 aircraft, and has already delivered a number of MkIIs to customers and builder assistant centers.

“There are customer aircraft that are sitting on the landing gear right now, getting ready for engine install,” Dan Hanchette said.

To begin with, you’ll shell out $183,400 for two kits that make up a base kit. Kit A includes fuselage, empennage and associated hardware, while Kit B includes wings, ailerons, flaps, landing gear and associated hardware.

Due to many requests, you can now get a pressurized model, which is an additional $39,000. The fuselage is completely different structurally.

“You cannot make a non-pressurized airplane into a “P” for pressurized,” he emphasized. “It has different stringers and more carbon fiber and carbon structural bands that go around the fuselage. It has pressure regulators and pop-off valves. That’s all part of that upgraded kit.”

The Viperjet MkII has been designed for easy construction. “Excel Build” technology, configured with timesaving subassemblies, is standard, and will save over 800 hours of build time. Viper Aircraft also has a Super Excel Builder Assist option, for an additional $75,000.

“We have over 200 jigs and fixtures,” Dan said. “If a customer orders this program, we’ll assist that customer. This is a customer-support option, so we encourage the customer to participate in parts of that buildup.”

The wing and tail come pre-mated to the fuselage.

“All these things are put together and then taken apart again for shipping to the customer, if they order that option,” he said. “They’re faced with system installation at that point. That option makes their airplane interchangeable. Because it was a factory-jigged aircraft, if they get a part damaged–let’s say a wing tip or a flap aileron–they can call the factory and say, ‘I need a left aileron.’ We can have one built, primed and sent off in a number of days. It’s got interchangeability like you would expect to see in a factory-certified airplane. We’re one of the very few kit companies that have taken it that far.”

He said that every one of Viper Aircraft’s customers is participating in the buildup of their aircraft.

“Some more than others, but they all want to go by the required 49-51 percent rule, so they’re having professional build centers assist them,” he said. “Some customers have their airplane sitting in their hangar or garage, and they’re building it up themselves as well.”

The delivery time on a Super Excel built airplane right now is about four months.

The cost of operation for the MkII is around $400 per hour, which is considerably lower than a VLJ or a business jet such as a Citation.

“Miles traveled, you’re going to be at about the same cost of running it as you would miles traveled in a small twin-engine aircraft,” Scott Hanchette said.

Power plant and avionics

When it comes to the power plant, the Hanchettes strongly encourage use of the GE CJ610/J85.

“All of our testing and flight data has been with the CJ610/J85,” Dan Hanchette said. “Those are the same engines; one is military and one is certified. But a customer can do what they want to do; we just won’t condone it. If it’s a larger engine, it could throw your weight and balance off. It could cause a lot of issues. When you deal with sophisticated aircraft like this, if you change one thing, it changes a hundred.”

He said his brother calls that the “donut theory.”

“It goes in a circle and it keeps on going and going,” he said. “You change an engine, as we’ve done before, and it ends up changing everything on the airplane. That’s what happened with the MkII. There’s a long list of things that changed, which made it a better airplane.”

The J85 engines Viper Aircraft gets are generally the 17/17A models and can be purchased, overhauled by their engine technicians, for around $100,000. The CJ610 can also be used, but carries a heavier price tag since it’s an FAA certified engine.

Avionics choices depend on how “mild to wild” a customer wishes to go. Viper Aircraft estimates you’ll spend $30,000 to $70,000 for an IFR panel. The Viperjet MkII prototype is flying with avionics from OP Technologies, based in Beaverton, Ore.

“A group of ex-Honeywell designers and engineers came up with a very affordable EFIS glass cockpit system and we’re running that in our airplane,” Dan said. “We love it. They’re great support.”

Future

The focus right now is on the Viperjet MkII but Viper Aircraft is also looking at the military aspect.

“There has been some interest from foreign countries in the Viperjet,” Dan said, adding that they’re in the middle of one negotiation right now. Although it’s only on paper, they’re also talking about the possibilities of a four-place aircraft, configured very much like the Viperjet.

The bottom line, according to Dan Hanchette, is that the Viperjet MkII is going to exceed your expectations.

“It has with most people who have flown it,” he said.

A deposit of $18,340 secures your serial number and puts you in position for planning assistance for your desired configuration.

For more information, visit [http://www.viper-aircraft.com].