By Larry W. Bledsoe

On Sunday, May 7, 61 years to the day after the Second World War in Europe ended, the Southern California Friends hosted a symposium honoring five American fighter aces. The symposium featured Mustang aces from the European theater and was held jointly with the Inland Empire Wing of the Commemorative Air Force at the unit’s hangar on Riverside Municipal Airport, in Riverside, Calif.

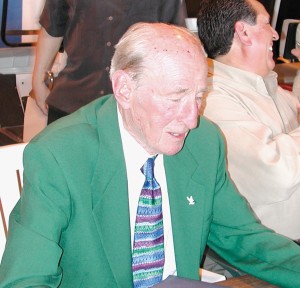

Lt. Col. Lawrence Powell

SCF President Scott Thomas, serving as moderator, introduced Lt. Col. Lawrence Powell from the 339th Fighter Group, with six victories. Powell explained that he flew 67 and three-quarter missions, saying he hadn’t quite made 68 missions, because he didn’t make it back on his last mission on Jan. 14, 1945.

Lt. Col. Lawrence Powell’s short stay in a German POW camp gave him a lifetime of memories, some of which he would like to forget.

On that unfortunate mission, he was the flight commander, and they were chasing a locomotive. He was down on the deck and didn’t see a wire until it was too late. Instead of snapping, the wire tore off some of his control surface. He struggled to keep the plane upright and gain enough altitude to bail out.

He recalled the mission had started at 8:00 o’clock and was scheduled to end at 10. After bailing out and landing, he noted his watch said 10:00 o’clock, and he ruefully thought his plane had finished the mission on time, just in the wrong place.

When a farmer came running towards him with a pitchfork in his hands, Powell realized the man didn’t have friendly intentions and threw his parachute at the pitchfork. The farmer then turned and ran away and Powell also ran—the other way into the woods—and evaded capture for two days.

He recalled that bunks in the POW camp where he ended up had no mattresses, just wood slats, and were stacked three high. It was so cold they started burning the wood slats and ended up with just a few slats, one for their feet, bottom, shoulders and head. He told how one night the slats moved, and he fell down on the bunk below, which in turn crashed through to the bottom bunk and then to the floor.

Powell and another POW, wrapped in a great coat trying to keep warm, ended up on the top of the pile, and it took 15 minutes to get them untangled. He remembered that the person on the bottom of the pile said he didn’t mind being there because that was the warmest he’d been for weeks.

As the last days of war came nearer, things became chaotic. Sometimes the POWs kept the guards safe so they could in turn protect the POWs, and the guards began trading food for cigarettes the POWs received in Red Cross packages.

At some point, the guards disappeared and the prisoners headed for the American lines. When they left the POW camp, Powell came into possession of a pot, which he took with him. At first he loaned the pot out to others to cook what food they could scrounge up. Then he started renting the pot for a portion of the food. It kept them alive.

One day someone gave them a chicken. They asked a farm woman to cook it for them in his pot. She did, and kept checking on the pot and adding things to it. When she finished, they were treated to chicken and dumplings.

Finally, on April 29, Patton’s troops liberated them.

Col. Ernest “Ernie” Bankey

Col. Ernest Bankey got his first victory flying a P-38 before transitioning to P-51s for his second combat tour and eight more victories.

Col. Ernest “Ernie” Bankey, from the 364th Fighter Group, with 9.5 victories, observed that fighter pilots didn’t have the luxury of being able to get up and stretch their legs or take a nature break on long flights, like a bomber pilot or transport pilot could. He said the three- to four-hour missions in a cramped cockpit of a fighter plane weren’t too bad, but the five- and six-hour missions were something else.

One of the most memorable sights he recalled during the war occurred when they flew fighter escort missions for large bomber formations of a thousand planes or more. The shear size of the formation, which stretched for miles, was unforgettable.

On one mission, he remembered lobbing a 500-pound bomb into a train tunnel and watching as a huge puff of black smoke exploded out both ends of the tunnel. He then went on to share some of his experiences during the Battle of the Bulge—experiences that he hadn’t been able to share with anyone for almost 30 years after the war.

He remembered shooting up trains and flying bomber escort duty. But the best memory he had was going home to his wife and his son, whom he hadn’t seen. He and his wife recently celebrated their 64th wedding anniversary.

Col. Arval “Robbie” Roberson

After flying with the 357th Fighter Group, Col. Arval “Robbie” Roberson went on to fly 100 missions in Korea and another 26 in Vietnam.

Col. Arval “Robbie” Roberson, whose Mustang was named Passion Wagon, was from the 357th Fighter Group. He recalled that on one mission he was flying wingman and his element lead was chasing an Me 110. They passed through some clouds, and when he came out, his element leader was nowhere in sight, but right in front of him was an Me-110. He gave it a quick burst, it exploded, and he flew through the debris.

Someone had told him that to become an ace, you needed to be a good pilot, and you needed to have luck. From his own experience, Robertson noted that luck meant that you have to be in the right place at the right time, just as he had been when he got the Me 110.

Roberson stayed in the service and flew 100 missions in Korea and another 26 in Vietnam. On one mission, his flight of P-51s were escorting RB-29s over North Korea when they got word that MiGs were taking off from one of the enemy fields below. This was early in the conflict, before F-86s arrived on the scene. He looked around and saw that the RB-29s had immediately aborted the mission and were heading back, which was OK with him, because the Mustangs were no match for the MiGs.

Lt. Col. Clyde East

Lt. Col. Clyde East started his aviation career in Canada. After the U.S. entered the war, he transferred to the USAAF. During his tours of duty, he acquired 13 victories. He was later assigned to the first U.S. jet squadron.

Lt. Col. Clyde East started his aviation career in Canada before the U.S. entered the war. At the time, one had to be 20.5 years of age before he could start pilot training for the Army Air Corp, and he didn’t want to wait. A few months after he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, the U.S. lowered its age restriction, but he decided to stay where he was.

After finishing flight training, East was sent to England where he flew Mustangs. After he had accumulated almost 300 hours in the Mustang, he was sent to train in Spitfires. After the U.S. entered the war, he transferred to the USAAF and flew Recce Mustangs with the 10th Photo Reconnaissance Group. He recalled that on D-Day he flew missions over Utah and Omaha beaches. During his tours of duty, he acquired 13 victories and became the top Recce pilot.

After returning to the States, he was assigned to the first U.S. jet squadron flying P-80s. He continued flying reconnaissance flights throughout his Air Force career. Most notable was his involvement in the Cuban Missile Crisis and later in Vietnam.

Capt. Clayton Kelly Gross

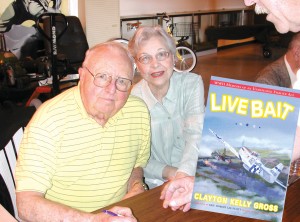

Capt. Clayton Kelly Gross, with his charming wife Ramona, signs his newly released book, “Live Bait.” During World War II, he had six victories to his credit.

Capt. Clayton Kelly Gross, past president of the American Fighter Aces Association, said that after he left the service he became a dentist. He said he was thankful that his involvement with the AFAA made it possible for him to personally meet most of the American aces and some of the aces from the other side.

Dr. Gross, who has six victories to his credit, said he was undefeated in aerial combat but was shot down once by ground fire. They had made a strafing run on a German airfield and saw the soldiers firing up at them, but he wasn’t worried about ground fire. After making the pass, he started counting the bullet holes in each wing, and the “one” through the top of his engine cowling, which had to have gone through the engine.

He climbed for altitude before the engine quit. When it did, he called Mayday and started to bail out, only to be restrained by his shoulder straps, which he had failed to undo. After he undid them, he started to bail out again, only to be stopped by the radio cord that he had forgotten to unplug. That done, he started to bail out for the third time, but as soon as he stuck his head out, the slipstream caught his goggles and pulled them away from his face, because he had forgotten to pull them tight. When he started to sit down, the loose goggles, no longer in the slipstream, snapped back in place with a thud.

Finally, on his fourth try, he was able to go over the side. His parachute snapped open at about 2,000 thousand feet above the ground. He was stunned by the silence but heard the crash of his P-51. He floated down near an open field and knew he was miles from the American lines. Shortly thereafter, a German halftrack pulled onto the other end of the field. Thinking he was about to become a POW, he stuck his hands up and walked toward it.

It was then that Gross noted a crudely painted white star over the German Swastika. He put his hands down, and the soldier pointed his rifle at him; up went his hands again. Since Gross was not in any standard uniform, the soldiers didn’t know what to make of him. He told them he was an American from the state of Washington, and they asked him the capital of the state. He replied, “Olympia.” They were from New York City and didn’t know if that was the right answer or not.

Next came the standard questions about baseball. He rattled off all the teams in the National League and started to name the roster for his favorite team. That got him an invitation into the halftrack, and eventually he arrived back at his base.

In 1996, Dr. Gross was chairman of the ace’s reunion in Oregon and was told about a German Me 262 pilot who lived in Vancouver. The German pilot was credited with shooting down 26 U.S. aircraft and had been shot down 16 times himself. After the reunion, they became friends and often swapped stories over a few drinks. Eventually, his German friend encouraged him to write about his experiences.

An occasional golfing buddy of Dr. Gross was none other than Col. Robert L. Scott. He, too, encouraged Gross to write his book. Finally, after more than a decade and several starts, his book, “Live Bait,” has been published. Based on the audience’s response to his stories at the symposium, it promises to be a great read.

It’s sad but true that we’re losing World War II veterans at an alarming rate, and the same holds true for the American fighter aces as well. Those who attend these symposiums are fully aware that the window of opportunity to meet such men as these will not be open forever. It’s an honor and a privilege to meet these aces and to have them share some of their experiences with us.

For information about the next SCF symposium call 949-632-6375 or email scf@prodigy.net.