The vertical stabilizer of the Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation’s C-54E, Spirit of Freedom, indicates it was once a Navy R5D. It’s one of only four airworthy C-54s in the U.S. Interior tours cost $5 for adults, $3 for children.

By Henry M. Holden

One of the main attractions at the recent Wings & Wheels Exp at Teterboro Airport was the Spirit of Freedom, the Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation’s Douglas C-54E. The foundation’s goal is preserving the memory and legacy of one of the greatest humanitarian and aviation events in history, the Berlin Airlift. The airlift changed the geopolitics of the world for more than 40 years.

Founded in 1988 and based in New Jersey, the foundation obtained and restored the aircraft, one of 330 that carried out the airlift, to flying condition. The foundation painted the airplane to represent the 48th Troop Carrier Squadron, one of the groups that participated in the event. Artifacts, displays and information explaining this history-making event fill the interior of the flying museum. Tim Chopp, founder and president of the Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation, spent four years looking for the right airplane for an educational exhibit about the airlift.

The foundation bought the airplane—one of four C-54s in the U.S. that are airworthy—for $125,000.

“I finally located this airplane in Canada in December 1992,” said Chopp. “We ferried it to New Jersey in mid-1993. We started flying the airplane in late 1994 and painted it in early 1995.”

World War II ends with divided allies

Photos and newspaper clippings in the upper display cases, installed just three years ago, illustrate the significance of the airlift. The military version didn’t include the bulkhead liners.

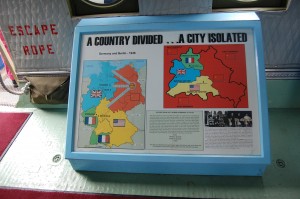

When World War II ended, the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain and France divided Germany. The Soviet Union took control of the eastern half of Germany, and the U.S., Great Britain and France took control of the western half. The capital city of Berlin, located in the middle of the Soviet-controlled half, was also divided into four parts.

By 1948, it became apparent that the Western powers’ plan to rebuild Germany differed from the Soviet Union’s. Currency, German unification and Soviet war reparations were among the many contentious issues; there would be no compromise. On June 24, 1948, the Soviets cut off all land and water access to West Berlin. More than two million Berliners were soon without food, water and fuel. The situation was grave.

When the blockade began, the Soviets believed the Western powers had only one option—to leave Berlin. But they underestimated the West’s airlift capabilities. On June 26, the first C-47s and C-54s landed at Tempelhof Airport near Berlin. Brig. Gen. Joseph Smith, airlift commander, dubbed the mission “Operation Vittles.”

The Soviets capitulate

On May 12, 1949, the Soviets capitulated, but the West continued supplying Berlin by air, in addition to land routes, to build up a sufficient supply of goods. The airlift officially ended Sept. 30, 1949. The U.S. and Great Britain delivered 2.3 million tons from 277,569 flights to Berlin; the C-47s and C-54s flew more than 92 million miles in order to do so.

“We call it our mission of history, education and remembrance,” said Kevin Kearney, foundation vice president. “Our purpose is to celebrate this pivotal point in history that’s almost forgotten in schools today. We want to educate kids about what happened in the last half of the 20th century; the Cold War was spawned from this event.”

Thirty-one Americans gave their lives

Mounted on the bulkhead just outside the cockpit is a memorial to the 31 American lives lost during the airlift. Kevin Kearney, the foundation’s vice president, is shielding the bright sunlight.

During the airlift, 101 fatalities occurred, including 31 Americans, mostly due to crashes.

“We want to share their story by putting it inside an airlift airplane,” said Kearney. “Some people will build a museum and then try to attract people to their venue. What Tim has created with this organization is a museum you can bring to the people, so it gets more exposure by traveling the country. We’ve traveled from Canada to California to Florida, and to what used to be Ramey Air Force Base in Puerto Rico, to spread our message.”

While Chopp’s mission is clear, the history of the airplane isn’t.

“We have the records from the Navy showing the airplane left Guam for Berlin,” said Chopp. “Then two years’ worth of records disappeared. We have a letter from the Navy indicating that it did, in fact, participate in the airlift, and we also have photos of it flying into Tempelhof Airport.”

The Navy had three squadrons in the airlift, VR-3, VR-6 and VR-8. The VR-6 and VR-8 squadrons were called corridor squadrons, and VR-3 was a support squadron. The foundation’s airplane was part of the support squadron. Its main job was to provide transatlantic support between Westover Air Reserve Base, Mass. (CEF), and Rhein-Main Air Base, in Frankfort, Germany.

L to R: Frank Benson, Kevin Kearney, Tim Chopp and Steve Grubesich are the Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation crew. The foundation needs volunteers who are willing get their hands dirty and go beyond their comfort zone to fix the airplane.

The Douglas Aircraft Company built this particular C-54E in 1945 for the Army Air Force. Six months later, they turned it over to the Navy. The Marine Corps flew it as an R5D out of the Marine Corps Air Station in El Toro, Calif., until it went into storage in 1973. Converted in 1976 to a civilian airplane, it flew auto parts in Canada until 1991, when it went back into storage. The foundation acquired it the following year.

“We began with very primitive displays,” said Chopp. “It’s been a slow process of building it to what it is today. What you see now is 12 years’ worth of work.”

When the foundation acquired the plane, the windows each had a cork in the middle, tied on a chain to the bulkhead. The corks plugged up the gun ports.

“When I got the airplane it still had the corks in the windows, but kids kept pulling them out,” Chopp said. “Kevin’s thinking at the time was to keep it as original as we could, but the windows were also pinged and marred. It was a nuisance to keep the corks in, so when we replaced the windows, we did away with the corks.”

The mission is getting the word out

Tim Chopp dreamed of creating an educational exhibit about the Berlin Airlift, especially to educate children. His intent is to celebrate the airlift as a pivotal point in history—one that is almost forgotten in many schools today.

The organization is very aggressive about presenting the educational aspect of the Berlin Airlift to the public.

“Doing about 30 shows, we put about 120 hours a year on the airframe,” he said. “The airplane is more than 60 years old, but it only has 27,600 hours on the airframe, so it’s still relatively young.”

They do other events besides air shows.

“We did a salute to veterans in Norfolk, Va. recently, and we’ll go to airport openings and special educational events for school kids,” he said. “We did one in Puerto Rico in March. We go to air shows for the funding, but we want to be a flying classroom. We want to focus on our mission—to educate folks, especially children.”

Next year, they’re hoping to return to Germany for the 60th anniversary of the airlift, depending on the funding.

“The world of transports in the warbird community is a lonely world,” he said. “We have to slug it out every year. We don’t have the bomber attraction. We’ve had this challenge with us from the beginning. It never ends, and we never let up on the mission to educate. We have a saying: ‘It’s all about the mission.’ We do what’s necessary to get the mission done. We’ve done our job if someone walks away from the airplane saying, “Wow, I learned something. It was well worth my time.'”

Finding the right people

One of the museum’s displays illustrates the division of Berlin. The Soviet occupation zone surrounded the American, British and French sectors of the city. The success of the airlift avoided an armed conflict with the Soviet Union.

The Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation has about 500 members, but Chopp said that like most groups, a small number do the actual work.

“We try to select crews that are here for the right reasons,” he said. “It’s tough to find the right people. We want someone who will do the glory jobs as well as the dirty jobs—people who are enthusiastic about the work, whether it’s sweeping the hangar floor, cleaning a toilet or helping show the plane. We want people who willingly go beyond their comfort zone to fix the airplane.”

Kearney said the team consists of “average people.”

“I’m a high school teacher and an aircraft and power plant mechanic,” he said. “Tim’s a retired corporate pilot and an A&P. Steve Grubesich, our chief loadmaster and mechanic, is also a teacher, and Frank Benson, our ground support and maintenance person, is a retired telephone company employee. We have volunteers from all walks of life.”

Chopp, who had his pilot’s license before he entered the Army, became an Army mechanic during the Vietnam years.

“I really wanted to be an Army pilot but it wasn’t in the cards,” said Chopp. “Now I’m really glad I didn’t, because it laid the ground work for this.”

After Vietnam, Chopp earned additional ratings and worked in corporate aviation. He’s also the aircraft’s commander.

“I love working on it as well as flying it,” he said.

Wintering the airplane

This photo was taken in 1994, two years before the Berlin Airlift Historical Foundation acquired their Boeing C-97G. The foundation plans to operate the Angel of Deliverance as a flying museum and classroom to educate about the Cold War.

Chopp said they finish their work every year at Kitty Hawk, N.C., on Dec. 17, and then hangar the aircraft at the old Floyd Bennett Naval Air Station/Floyd Bennett Field (NY22), in Brooklyn, N.Y.

“We try to beat any weather because Floyd Bennett is a closed airfield,” he said. “The New York City Police Department maintains their helicopters there and we need to get special permission every year to return. We’re allowed in during December and we’re out in April. The National Park Service manages the hangar; we trade educational use of the airplane in exchange for hangar space. It’s called the In-Park Interpretative Program. It’s a win-win for both sides.”

The foundation’s next project

Chopp said their next project is a Boeing C-97.

“We have one in the hangar in Brooklyn,” he said. “It will be a Cold War museum. We’ve had the airplane for 11 years and we’re about to go for its initial inspection. With any kind of luck, it’ll be ready in about 14 months.”

He said the Air Force used the Angel of Deliverance during the Cold war to deliver food, cargo and fuel as an aerial tanker.

“We plan to tell the story of the Cold War, from the Berlin Airlift of 1948 to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989,” he said. “The C-97 is the unsung hero of the Cold War. Before the KC-135, it was the airplane that gave the Air Force its global reach.”

For more information about the Spirit of Freedom, visit [http://www.spiritoffreedom.org].