By Di Freeze

Several years ago, producer Dean Devlin sent Tony Bill a script. Attached to it was a note to his friend that said, “This is the movie you were born to direct.” Bill read the script based on the Lafayette Escadrille and wholeheartedly agreed. There were several reasons he did.

“It’s not just the aviation,” Bill said about “Flyboys,” produced by Devlin and Mark Frydman. “It’s also the fact that I very much enjoy discovering new, young actors and working with actors. It’s an actor’s movie. And it’s a movie that’s really about the people; it’s not just an equipment movie.”

You’d have to know a little about Bill, who lives in Venice, Calif., with wife Helen Bartlett, his producer/partner in Barnstorm Films, to fully understand that statement.

Growing up in San Diego

Born Aug. 23, 1940, Tony Bill grew up in San Diego, where it was impossible to escape an interest in either airplanes or boats.

“In San Diego, especially in the ’40s and ’50s, there was nothing but airplanes all around you,” he said. “Airplanes were taking off to go to World War II and returning from WWII. Convair was there, and Consolidated made airplanes there. Lindbergh took off from San Diego. It’s an aviation-oriented town. I guess I was like any other little boy who dreamed of flying airplanes.”

Lindbergh Field was the main airport in San Diego, but that wasn’t where Bill hung out.

“We used to go on weekends to see the road races at Torrey Pines, a little bit north of San Diego,” he said. “Near the site of the road races was a very famous glider port (Torrey Pines Glider Port), so in the background, these gliders were always flying. That’s where I first got the bug to fly gliders.”

Bill soloed a glider at 14. Although his father wasn’t a pilot, they had similar interests.

“He was kind of an aviation bug, too, and he was a sailor,” Bill said. “We had a sailboat. There’s not too much difference between flying sailplanes and sailing sailboats.”

It wasn’t until about 20 years ago that Bill gave powered flight much thought.

“I took an aerobatic ride in a Pitts, and that got me hooked,” he said. “Ever since then, I’ve been an aerobatic pilot and a powered pilot.”

He said he still likes gliders, but not “as avidly as some people.”

After going for a ride in that Pitts biplane, Bill decided he wanted to do aerobatics, and set out to get whatever ratings he could.

“I went through the ranks of the powered flight ratings, through my commercial, twin and instrument, multi-engine and seaplane ratings,” he said.

Academy Award winner Tony Bill has been flying since he soloed in a glider at 14. He presently owns a Marchetti SF260.

The first aircraft he bought was a 1946 Globe Swift, previously modified for aerobatics. When it came time for lessons, he took them from Randy Gagne. The next step was entering aerobatic contests, which he did for several years, through the 1980s.

Besides the Swift, Bill has owned a number of aircraft, including a Cub, a twin-engine Cessna 310, and his present aircraft, a Marchetti SF260. The single-engine aerobatic airplane is made in Italy and has earned the nickname of “The Ferrari of the Sky.”

“It’s a very nimble, fast airplane,” Bill said. “Along the way, I also flew a lot of friends’ airplanes.” That includes military jets, such as the T-38, T-2 and F-18.

Show biz

Bill attended Notre Dame, majoring in English and art. While in school, he did a little acting. After graduating, that seemed like a logical summer job.

“Acting was the only thing I knew how to do that I thought I might get paid for,” he said. “I went to Los Angeles. Luckily, the summer job I got was costarring in a movie, so I got interested in the movie business because I was in it.”

That movie was “Come Blow Your Horn.” Bill played the younger brother to Frank Sinatra’s character; Jill St. John also starred in the comedy. Throughout the coming years, various directors, including Sydney Pollock, Terrence Malick, Steven Spielberg, Francis Coppola and Hal Ashby, cast Bill in roles. Others, such as Sir Carol Reed and John Sturges, served as mentors.

Although Bill has continued to act over the years, he’s never had the desire to be “a movie star.” His goal was always to work on the other side of the camera as a filmmaker. About seven years after acting in his first film, he made the leap to producing with “Deadhead Miles” (1971), and followed that with “Steelyard Blues” (1973). His next feature, “The Sting” (1973), brought him an Academy Award for Best Picture and won six additional Oscars; it also became one of the highest grossing films in history. His other production credits include “Taxi Driver” (1976), “Hearts of the West” (1975), “Boulevard Nights” (1979) and “Going in Style” (1979).

Bill made his directorial debut with “My Bodyguard” (1980). He also directed “Six Weeks” (1982), “Five Corners” (1987), “Crazy People” (1990), “Untamed Heart” (1993) and “A Home of Our Own” (1993). He found it particularly satisfying when he became known as an “actor’s director.”

“Flyboys”

Dean Devlin, the founder of Electric Entertainment, is always on the lookout for good scripts. The co-writer and producer of “Stargate,” “Independence Day” and “Godzilla,” as well as producer of “The Patriot,” was very impressed when he saw the original screenplay for “Flyboys,” by Phil Sears and Blake Evans. Knowing of Bill’s reputation as a consummate independent producer/director who thrives on discovering new talent—both writers and actors—it’s understandable that he thought of his friend first when he read the script.

L to R: Tyler Labine (Briggs Lowry), David Ellison (Eddie Beagle), Martin Henderson (Cassidy), James Franco (Blaine Rawlings), Abdul Salis (Skinner), Keith McErlean (Toddman) and Philip Winchester (Jensen) portray members of the Lafayette Escadrille.

Devlin, who knew Bill’s work well and had been a fan of it for some time, was thrilled when Bill was as excited about the project as he was. But the making of the film—a story of “love, loss and adventure”—wouldn’t be an easy road.

Bill says that due to his desire to see “Flyboys” made, he broke a few rules regarding the film. One was “never make an independent movie without distribution in place,” and two was “never spend your own money.” He adds one he’s come up with: “never wait around, turning down work, in the hopes that someone else will get a movie financed.”

He said that while Devlin was spending his own money trying to get “Flyboys” made without a distributor, he turned down feature directing jobs, in case Devlin called with a start date. In the meantime, he directed a few movies for cable, and when he needed cash, he sold items he had collected, including beloved early aviation books and American literature first editions.

Five years later, it looked as if most of the financing was in place, as well as “an incredibly ambitious and original concept.” That concept was to “make the movie completely independently—no studio, no distributor, no foreign sales,” and they would cast only actors who were right for the parts.

When they decided they needed to quickly go forward, before the money was all in place, Devlin pulled out his own checkbook. One of the biggest expenses would be aircraft. Bill explains that the last time anyone made a big budget movie about WWI aviation, and the birth of aerial combat, was 40 years ago. That was “The Blue Max” (1966), directed by John Guillermin.

Before that, he said, the only “decent” movies date from more than 75 years ago: William A. Wellman’s “Wings” (1927), Howard Hawks’ “Dawn Patrol” (1930) and Howard Hughes’ “Hell’s Angels” (1930).

Bill and Devlin had a difficult task ahead of them. One problem was that the script called for several squadrons of airplanes, including dozens of French Nieuport 17s and German Fokker Dr1 triplanes. The aircraft wouldn’t just be needed for ground shots either. They’d be in the air, “dogfighting, crashing and burning.”

“In the ’20s and ’30s, they had plenty of aircraft and pilots to fly them,” Bill said. “You could crash and burn real WWI airplanes all day long for a couple of hundred bucks each; stunt pilots got 25 bucks a day (and several were killed.) Those days, and those airplanes, are long gone.”

In that area, Mike Patlin, the American aerial coordinator, got help from Sarah Hanna, the daughter of Ray Hanna, the former leader of Great Britain’s Red Arrows aerobatic team. With expertise in running a museum and air show business, the Old Flying Machine Company, in Duxford, England, with her father, Hanna helped Patlin come up with a fleet that included two German Fokker DR1 triplanes, a British Bristol F-2 fighter, a French Bleriot XI and a Royal Aircraft Factory SE-5a.

Patlin also enlisted the help of Ken Kellett and Andrew King. King, who flew World War I vintage aircraft at New York’s famed Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome between 1982 and 1986, now works on vintage aircraft at his airplane repair and restoration business in Virginia. Kellett, a restorer at the Fantasy of Flight in Florida, owned by Kermit Weeks, suggested using a Nieuport 17 replica that had been suspended over the museum entrance for years. Although the airplane wasn’t flyable, Kellett had it in the air in six weeks. He also tracked down a replica two-seat Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter for use in the film.

The fleet of aircraft assembled is said to be second only to those amassed by Howard Hughes for “Hell’s Angels.” The Bristol fighter is the last flying model of its kind in the world, and the Bleriot is the oldest flying aircraft in the world.

A total of seven Nieuports were used in the film, including two from the United Kingdom. Missouri-based Robert Baslee, who builds full-scale replicas of vintage aircraft using ultralight builder techniques, was asked to fill the void by building four flyable replica Nieuport 17s. When Baslee got involved, Bill stressed that the aircraft needed to be done within 10 weeks. They turned their attention to other problems, and were relieved when Baslee finished the aircraft in 54 days.

During filming, Bill added another aircraft type to what he’s flown.

“I flew the Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter,” he said. “I thought it was a very nice flying airplane. Nicer than I expected. But they’re all very, very undependable engines, and very marginal handling airplanes.”

Bill said that the problem with any of these airplanes is that they’re very tricky and dangerous to fly.

“In varying degrees, they all have their idiosyncrasies,” he said. “They were all airplanes that were built at a time when the airplane itself was in its infancy.”

Aircraft were lightweight during that period, but he said the ones that were built for the movie were even lighter.

“They were just a little more squirrelly than the other ones,” he said.

He said there were a couple of “close calls” during filming, but nothing too bad.

“Fortunately, nobody got hurt, and no airplanes got damaged beyond what could be repaired in a day or two,” he said.

When it came to shooting aerial sequences, Bill figured they were ahead in that area. Instead of early 20th Century cameras and film stock, they had early 21st Century cameras, as well as video, green-screen and CGI (computer-generated imagery). The hope was to find a way to shoot on video and transfer to film. However, it initially seemed that no video format or camera had been introduced that could transfer the look they needed for the big screen.

Jennifer Decker, who makes her American debut in “Flyboys,” plays Lucienne, James Franco’s character’s love interest in the film.

Bill strongly felt that any “real flying” that could be done should be, but he knew not all of it could be real. He also firmly believed they needed to do whatever it took to “put the audience in the pilot’s seat.” The intent would be to “throw them around in the air,” just the way the pilots of WWI were thrown around.

“We needed our planes and pilots to be up close and personal,” Bill said. “When World War I broke out, most people had never seen an airplane, much less flown in one.”

He described the airplanes of World War I as “the space vehicles” of that time.

“Pilots weren’t in a cockpit,” he said. “They didn’t have any protection around them or parachutes. A mere spark was almost certainly fatal. They were basically flammable, flying targets.”

The actors in “Flyboys” would be portraying “knights of the sky,” who were shooting at an enemy whose face they could see, while that enemy was shooting back at them. They were “flying, literally, for their lives.”

“I wanted the audience to experience the excitement and the terror of that aerobatic aerial combat,” Bill said. He also told Devlin that he’d consider the flying sequences a success if he could “make just one member of the audience airsick.”

The solution to how to make that happen eluded them, but they “forged on.”

The Lafayette Escadrille

To make their story real, Devlin and Bill were equally concerned about choosing the perfect actors for the roles. The real-life story of the Lafayette Escadrille, the first American fighter-pilot squadron to see action in World War I, begins in April 1916, in Luxeuil, when the “Escadrille Américaine” (the name was later changed) was formed prior to the entry of the U.S. into the war.

The Lafayette Escadrille was a squadron of the French Air Service, the Aéronautique Militaire, composed largely of American fighter pilots. Two men mainly fought to persuade the French government that a volunteer American unit fighting for France would be valuable. Those men were Dr. Edmund L. Gros, director of the American Ambulance Service, and Norman Prince, an American expatriate already flying for France. It was hoped that the American public would recognize the efforts and that those efforts would rouse interest in abandoning neutrality and joining the fight.

French Captain Georges Thenault commanded the squadron, based near the German border. The Lafayette Escadrille, with 38 pilots, saw its first major action at the Battle of Verdun. Although it suffered heavy losses, other Americans quickly arrived from overseas to fill the gaps. The volunteers were so numerous that a “Lafayette Flying Corps” was formed, which attracted 265 American volunteers. Many of these young volunteers were well-educated, aristocratic, or in the case of the Lafayette Escadrille, Ivy League graduates.

Producer Dean Devlin, the founder of Electric Entertainment, overcame several hurdles to get “Flyboys” made.

Of the 63 members who died during the war, 51 lost their lives in action against the enemy. Credited with 159 enemy kills, the Lafayette Flying Corp amassed 31 Croix de Guerre, and its pilots won seven Médailles Militaires and four Légions d’Honneur. Eleven of its members were flying aces. The core squadron suffered nine losses and was credited with 34 victories.

Bill explained that the actors in the epic motion picture don’t bear the names of actual Lafayette Escadrille members, but that each character was derived from a real person, or a composite of various people.

“The same with events,” he said. “There’s nothing in the movie that didn’t happen in real life.”

“Flyboys” centers on the idea that each pilot had his own motivation for joining the French, beginning a “great, romantic adventure,” while becoming the world’s first combat pilots. Some sought “adventure and a new start in life,” and others, perhaps, a chance to make their families proud.

For their cast, Bill and Devlin interviewed actors in Los Angeles and London, coming up with Golden Globe Award winner James Franco, New Zealander Martin Henderson and Jean Reno as leads. Franco has recently starred in “Spider-Man 2,” “Annapolis” and “Tristan & Isolde.” Henderson appeared in “The Ring” and “Bride and Prejudice.” Jean Reno has most recently been seen in “The Da Vinci Code” and “The Pink Panther.”

“Flyboys” begins when four Americans arrive in France, eager to learn how to fly. Assigned to their own squadron, the new aviators are commanded by the war-weary Captain Thenault (Jean Reno) and the equally battle-scarred American pilot Reed Cassidy (Martin Henderson), the squadron’s top ace and the cynical sole survivor of his group, who is loosely based on French-American fighter pilot Raoul Lufbery. Ignoring Cassidy’s grim admonition to quit and go home before they meet their inevitable fates, the men study, vigorously train and finally learn to fly.

Texas-born Blaine Rawlings (modeled after “Balloon Buster” Frank Luke and played by James Franco) finds himself evicted from his family’s 900-acre ranch, and sees a new future in a newsreel reporting on the squadron’s heroics. French Foreign Legion recruit Higgins (Christien Anholt) transfers to the squadron from the ambulance corps. Nebraska-born William Jensen (Philip Winchester), the son of a Calvary officer, joins to uphold the family tradition of military service. Briggs Lowry (Tyler Labine) enlists to make something of himself, yielding to the pressure of his wealthy and powerful father. Eddie Beagle (David Ellison), one of the squadron’s most hapless pilots, seems to be escaping from his past.

Abdul Salis plays Skinner, a composite character partially based on the real-life Eugene Bullard, who made aviation history as the first black military pilot. He wants to defend France, a country that has shown him tolerance by allowing him to compete and become a boxing champion, whereas in America he wouldn’t be allowed inside a cockpit. Even the lion in the movie is based on the squadron’s real mascot. “Chaka” portrays “Whiskey,” who was acquired as a cub on a trip to Paris by several of the Escadrille pilots and became their mascot. “Soda,” another young lion, later joined him.

In time, the young Americans prove themselves, always aware that a pilot’s life expectancy is three to six weeks. Fighting a war that wasn’t theirs, these young, naïve adventure-seekers slowly learn the true meaning of love, brotherhood, heroism, courage and tolerance, and, in return, gain a true reason to risk their loves.

You won’t recognize many faces in this movie. That’s completely intentional.

“We spent a long time casting it,” Bill said. “One of the challenges was that we needed to spend as much money from our budget as possible on English passport actors. Some of our money came from English tax shelter money, so we had to find as many actors as we could that were able to play Americans, but who were on English or British passports.

Bill is satisfied with the casting, and believes they’ve uncovered hidden treasures. On a day trip to Paris, they signed the female lead, Jennifer Decker, 21, who makes her American debut in “Flyboys.”

“I think that Jennifer is a huge find,” he said of the actor who plays Franco’s love interest in the film. “She practically steals the movie, and she’s not even a central character. I think she’s the heart of the movie.”

One person they cast was already considered a “star.” In 2003, it was announced that six young, promising aerobatic pilots would be center stage at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh in their roles as the “Stars of Tomorrow.” The young pilots, brought together by renowned aerobatic and air show performers Sean D. Tucker and Mike Goulian, showcased their talents during the daily air shows at the fly-in that year.

When Tucker and Goulian looked for pilots with exceptional flying skills, as well as passion, one person who caught their attention was David Ellison, the son of Oracle founder Larry Ellison. At the time, Ellison, who had been a competitive ice dancer in high school, was attending the University of Southern California, majoring in film. Mentored by Tucker and Goulian, Ellison went through intensive training.

Bill and Devlin also recognized something special in Ellison, who took his first flying lessons at 13 and became one of the country’s top-ranked aerobatic pilots. And the aspiring actor recognized the importance of the film. He put up money for the film’s budget before agreeing to sign on as Eddie Beagle.

With the aircraft and actors in place, Bill and Devlin were excited to discover a new camera utilizing an unproven technology and a revolutionary concept. After several weeks of testing the Panavision Genesis 35 mm digital camera, they decided to go for it—only two weeks before shooting was to begin.

The biggest concern now was money. Finally, 10 days before the start of principal photography, financing was completed.

“Flyboys” was filmed in spring 2005, in the countryside in the south of England. A majority of the film was shot on location in parks and open fields. The primary location was a park at the Royal Air Force airfield in Halton.

“We filmed at different sites, but the bulk of the work was done at a large aerodrome we created there,” Bill said.

The production team was able to find plans and images of almost everything required to make the film as authentic as possible. The Imperial War Museum provided information and more was gleaned from Tony Bill’s personal library of research materials, as well as extensive French documentation of the period.

The pilots

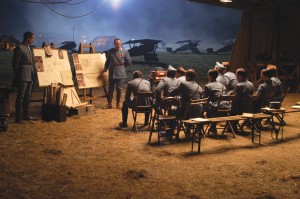

To prepare for their roles, cast members took a series of aviation classes to familiarize themselves with the aircraft and equipment.

“I forced them into training in planes just like their characters,” Bill said. “I also talked to them about the realities of flying aerobatics … and things to expect in the air. Then we took them up, each of them, for two or three flights a day and filmed them in a real, open-cockpit aerobatic airplane, flown by Nigel Lamb (eight-time British unlimited aerobatic champion). I had him do everything: rolls, loops, spins.”

Under the tutelage of the legendary aerial unit coordinator, Ray Hanna (who died shortly after shooting “Flyboys”), Ellison and the rest of the main cast received two weeks of flying orientation, learning the basics of flying primitive aircraft. Six of the world’s top aerobatic pilots worked with the actors to create the film’s extensive flying sequences.

Tony Bill (right) visits with, L to R, Ron Kaplan, Sean Tucker and Kermit Weeks at the AirVenture premiere of “Flyboys.”

Other British pilots responsible for flying the aerial sequences were Alister Kay, an eight-time UK gliding champion and an air show aerobatic pilot; John Day, who flew one of the Nieuport 17s, which he built; and Anna Walker, a professional test pilot and WWII warbird pilot. The aerial unit included two American pilots, Andrew King and Ken Kellett. Fred North, a Frenchman, flew the helicopter camera ship.

With the director and one of the main stars of “Flyboys” already avid pilots, James Franco soon tried his hand at flying as well. He took flying lessons and soloed during filming. Another cast member was familiar with the cockpit.

“Martin Henderson had been taking some flying lessons in New Zealand or Australia for a previous film,” Bill said.

The fruit of their labor

Since the filming ended, various venues have presented an opportunity for Bill to share his enthusiasm regarding the project. One recent occasion was the National Aviation Hall of Fame Enshrinement Ceremony and Dinner. Bill served as the event’s emcee.

“He won over our audience with his charm, wit and knowledge of aviation history,” said NAHF Executive Director Ron Kaplan, adding that Bill exceeded expectations as emcee for the prestigious event. “The fact that ‘Flyboys’ is based upon the exploits of two of our enshrinees, Raoul Lufbery and Frank Luke, and a nominee, Eugene Bullard, was icing on the cake, especially after our audience was treated to the movie trailer scenes as part of our introduction of Tony.”

Karl Koeppen has handled all the aviation publicity for the film. He worked to make “Flyboys” one of the big buzzes at Oshkosh this year. The movie had its “aviation world” premiere at AirVenture, at the EAA AirVenture Museum. The excitement was enhanced by the fact that David Ellison took the opportunity to fly his Extra 300 as a promotion for the film.

Those who weren’t lucky enough to attend that special premiere don’t have much longer to wait. The film opens in theaters September 22. Bill is confident that pilots and non-pilots alike are going to enjoy “Flyboys.”

“They’re going to see a time and a place that’s virtually never been on film, with the exception of maybe ‘The Blue Max,’ which wasn’t really about this subject,” Bill said. “No one’s made a movie like this since 1930, and all of them were in black and white. This is the first time anybody’s seen a realistic, in-color portrayal of the period, of those airplanes and of aerial combat. Viewers are in for a great ride, literally. Most people have never flown in an open-cockpit biplane, doing aerobatics in the sky. They’re going to be able to experience what few people ever have.”

Written by Oscar-winning screenwriter David S. Ward (“The Sting”),”Flyboys” is presented by Electric Entertainment in association with Skydance Productions and Ingenious Film Partners. To view a preview of “Flyboys,” visit [http://www.flyboysthemovie.com].