By Fred “Crash” Blechman

Most pilots in our squadron didn’t like to do it. They thought it was boring and could be dangerous. I volunteered to do it whenever the opportunity came up.

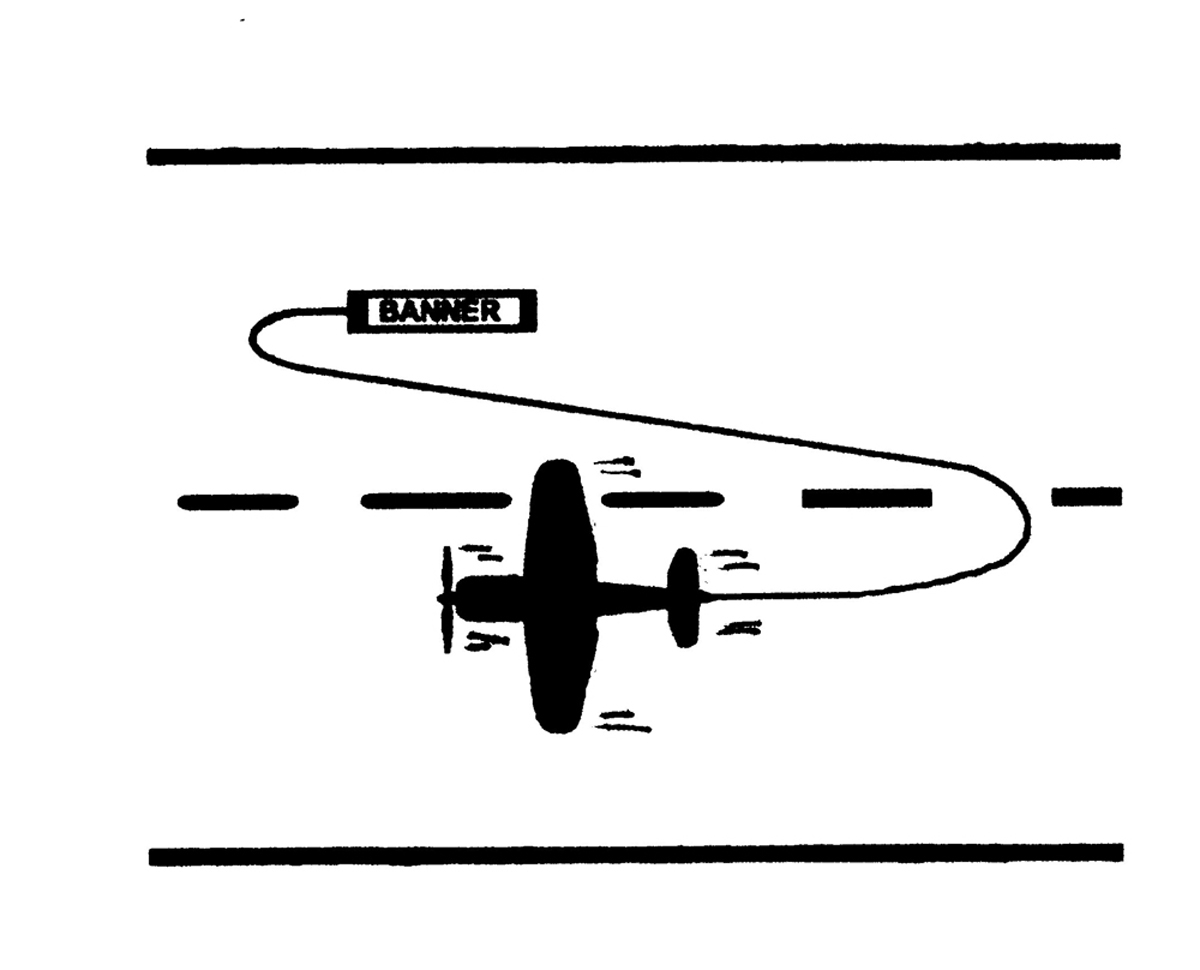

The banner was placed ahead and to the right of the Corsair. A maximum-climb takeoff yanked it off the ground before it could be damaged by dragging it on the runway.

What was “it”? It was piloting an F4U-5 Corsair while towing an aerial gunnery target. Why was it boring? Because it took forever to get to the aerial gunnery practice altitude. And why was it dangerous? Because you could get shot down!

Then why would I volunteer to do this? When I joined the Navy VF-14 “Tophatters” fighter squadron in September 1950, I was a “nugget” with my brand new pilot “wings of gold,” having just completed Navy flight training. I had trained in the earlier version F4U-4, and now was flying the faster, more powerful, more advanced version of the Corsair. I was gung-ho, still filled with the enthusiasm of flying. I was also young and innocent.

Even though we were based in Jacksonville, Fla., it was expected that we would be called to duty in the Korean police action that had started a few months earlier. We were expected to be combat ready, and were constantly training in bombing, rocketry and gunnery. When scheduled for aerial gunnery practice, a squadron pilot would tow a target banner with one of our squadron Corsairs.

If you’ve ever been in the military, you know there are rules—and more rules. Even though we were fighter pilots, WWII was over, and some of the previous latitude-allowed pilots had now become more restrictive. “Flat-hatting” (flying low over populated areas) or “hot-dogging” (aerobatics around the airport, for example) could get you grounded. We weren’t even allowed to make “hot” takeoffs (sudden drastic climbs).

But, if you were towing a target banner, you had to make a steep climbing takeoff! Why? To keep from dragging the target on the ground and clear any structures in the takeoff path. Not only that, but if you were flying the tow plane, you got to watch the Corsairs make their gunnery runs from the best seat in the house—although you could be shot down by accident, as I’ll explain.

Again, I was young and innocent, so when the opportunity arose, I volunteered to tow the target. I’d like to say that I recall every detail of those towing flights, but when I decided to write this story, I realized some of the details had faded in the last 55 years—so I asked for help.

I contacted Jim Morin (who retired as a rear admiral), A.G. Wellons (retired as a captain) and Randy Moore (retired as a commander), three of the pilots I flew with in VF-14, and asked them for their recollections about some towing flight specifics. What was the climbing speed and rate of climb? How high did we go before leveling off and how long did it take? What was our towing speed? How was the banner connected to the Corsair, and how was it released?

Their responses varied in details, but I have averaged their recollections with mine for the following description of one of my particularly exciting towing flights. It was one of those typical sunny Florida late mornings, mostly clear skies with cotton cumulous clouds floating around, some with showers underneath. I was scheduled to tow a gunnery banner up to 15,000 feet over the Atlantic off the coast of Jacksonville from Cecil Field, where our Air Group One was based. I climbed in a Corsair, cranked it up, and taxied out to the active runway, to the left of the centerline, and at the end of the tow cable.

Already laid out about 300 feet in front and on my right was the 40-foot-long flat banner. At the front of the four-foot-wide banner was a heavy metal bar, and at the end of the banner on the side closest to me was a weight to keep the bar vertical in flight. One of the squadron crew members hooked the end of the cable to a tow hook under the tail of the Corsair, and yanked on it to be sure it was secure.

With clearance from the control tower for a tow takeoff, I applied full brake pressure by depressing the tops of the rudder pedals and pulled the joystick all the way back to hold the tail down. With full flaps and the prop set to full rpm, I advanced the throttle to 44 inches of manifold pressure—about all I could use before the tail would try to come up. The Corsair leaped forward as I released the brakes and advanced the throttle to full power. It took a few seconds for the F4U-5 automatic power unit to bring the manifold pressure to about 54 inches—full power without water injection—as the Corsair increased speed. I relaxed the stick for a slight nose-down position to allow maximum acceleration.

As I passed the banner on my right, I had about another 300 feet to go before I would be dragging the banner on the ground—which could bend the banner front metal bar and cause erratic banner fluttering in the air. As my airspeed increased to about 110 knots, I pulled back on the stick and put the Corsair into a steep 30-degree climb, carefully watching the airspeed indicator as it dropped toward 90 knots, where I shoved the stick forward to prevent stalling.

Hopefully, I had yanked the banner off the ground before it dragged. Now with the banner unfurled and vertical—which I could see in my three cockpit rear-view mirrors—I maintained a shallow climb and full power until I reached a climbing speed of 140 knots at a rate of climb of about 500 feet per minute. I reduced power to maintain that rate of climb with the high drag and weight of the banner and cable I was pulling. With my long Corsair nose in a climbing attitude, I couldn’t see straight ahead; to my rear, outboard of the banner, was a Corsair from our squadron acting as a safety pilot and escort.

About 15 minutes after I took off, the other squadron Corsairs on this gunnery practice flight took off and we rendezvoused in the gunnery area off the coast at 15,000 feet. I leveled off and flew a constant heading at 160 knots, as the other Corsairs climbed about 2,000 feet above me. They paralleled my path, forming into a right step-down echelon about 15 degrees to the right of my nose. One by one, about five seconds apart, they peeled off to the left in a tight diving turn.

This was fascinating to watch—just like in the movies! The Corsairs each flew in a pursuit curve, swinging around the back and below the banner, the pilot judging the proper deflection lead, and firing his four 20 millimeter cannons at the target. For scoring hits, the nose of each 20 millimeter shell in each plane was painted a different color, so that when (and if) it hit the banner, it left a colored hole that would identify which pilot had made the hit.

However, target fixation could result in the tow plane getting hit! While firing at the banner, if the pilot got below and directly behind it, his bullets could arc upward and hit the tow plane! This has happened. Target fixation could also cause the pilot of the firing Corsair to actually hit the banner with his airplane! Ouch! And there have been occasions when the tow line was shot apart, releasing the banner to dive 15,000 feet into the ocean.

Anyhow, watching the Corsairs make their firing runs and then reforming above, ahead on the left, and making gunnery runs from there, was like watching an air show—and I had a grandstand seat! They alternated each run from a perch to port or starboard (left or right for you landlubbers).

Finally, with my fuel running low, I turned back to Cecil Field to drop the banner and land. But as I approached the airport, I found a large cloud over the far end of the duty runway, with pouring rain underneath. With little fuel, and no nearby alternate airport, I had to drop the banner before I could land!

I descended to 800 feet and flew above the runway. Just before I entered the rainstorm, I pulled the tow line release handle in the cockpit; no sooner did the tow line and banner drop away, than I found myself in instrument conditions. Maintaining my altitude, I made a gradual left turn to the downwind heading and soon broke out of the rain. The runway was on my left, with the upwind end in the clear. I made a standard landing approach, landed, and as I was rolling down the runway, I went right back into the rain. Weird!

With greatly reduced visibility in this downpour, I had to be careful not to run off the side of the runway. The Corsair, with its long nose and tail wheel, required constant S-turning to see ahead when taxiing, and in this pouring rain I could hardly even see the sides of the runway. I made it back to tie-down, and I don’t recall ever having to land in a heavy rainstorm again.

With the excuse to make a “hot” takeoff to avoid dragging the banner on the runway, and to get a prime seat to watch this mini air show, I looked forward to other banner towing flights.

Fred “Crash” Blechman’s two flying books, “Bent Wings—F4U Corsair Action & Accidents: True Tales of Trial & Terror!” and “Flying With the Fred Baron,” are available at [http://www.amazon.com] or [http://www.bn.com].