In 1930, Pacific Northwest aviation pioneer Vern C. Gorst was the first to suggest uniting four fledgling airlines-including his own, Pacific Air Transport-to create United Aircraft and Transport Holding Co. His idea, and his involvement in the subsequent creation of that nationwide airline with Bill Boeing and others, earned him a place in aviation history as the “grandfather” of United Airlines.

While that footnote to UAL history surfaces from time to time, including mention in United’s website history, it seems that not many people outside of family members who still live in Oregon and Washington know about Gorst today. In an earlier generation, however, this energetic, innovative entrepreneur developed a long list of notable “firsts” in his lifetime, most of them in early aviation endeavors.

“These old aviators took the risk and did things first. They were inspirational,” said Wendy Brady of Port Orchard, Wash., a great-great-niece of Vern Gorst. “When he started Seattle Flying Service in 1928, he flew off the ‘Gorst Sand Lot,” where Boeing Field is today, using an 1,800-foot-long runway of gravel and clinkers on a layer of soft sand and sawdust. From 1926 to 1928, Gorst’s field was Seattle’s only commercial airport. He flew OX5 Travel Airs and later became a member of the OX5 Aviation Pioneers Hall of Fame.”

One of many pioneers involved in the early days of aviation history, his ventures and successes rank him among the most important names in early flying chronicles in the western states. He flew the first coastal air mail routes, started several airline companies-Seattle Flying Service, Pacific Air Transport, Gorst Air Transport, Barnes and Gorst Air Mail, and Victoria Air Mail-and pioneered Alaskan aviation, in the state where he had once mined nuggets during the late 1890’s “gold rush” years.

His determination and risk-taking established him as a true adventurer, on the ground and over waterways, as well as in the skies. Creating new ways to move people and freight fascinated him, even as a boy, perhaps influenced by his train-and-boat journey from the family’s home in Bell Prairie, Minn., to Seattle. Born Aug. 18, 1876, the sixth child in the family, Gorst’s parents chose Centennial for his middle name, to honor the country’s first 100 years of independence.

In 1888, his family arrived by rail aboard a Northern Pacific Railroad train, and then settled across Puget Sound on the Kitsap Peninsula, a journey made aboard a chartered sailboat that ended up being towed by a steamboat when the wind died down, according to a newspaper feature story on Gorst’s life years later.

Gorst’s father, John, bought 60 acres at the head of Sinclair Inlet that year. When his brother, Sam, arrived from the Midwest in 1890, the brothers bestowed the family name on nearby Gorst Creek and the Gorst community, which today is a 1,700-resident hamlet near Bremerton. Samuel bought 160 acres from the Port Blakely Mill Co. on the north side of Gorst Creek in 1895, and the brothers set up a logging business.

The Gorst’s pioneering neighbors included the Johnson Curtis family, whose son Edward later became famous for his Indian photos, while Edward’s brother, Asahel, became the foremost scenic and commercial photographer in the Pacific Northwest, Alaska and the Klondike. Having grown up together, Gorst and the Curtis brothers kept in touch for many years. A letter from Asahel to Vern Gorst in 1927 thanked him for his invitation for Curtis’ first flight, telling Gorst “I think if you had some good photographs taken along the route of your flight between Seattle and San Diego it would do considerable to stimulate the travel.”

Even as a youth, Gorst’s enterprising spirit surfaced. At 13, he entered the transportation business by becoming the first to ferry chickens across Port Orchard Bay for residents, using his own homebuilt log raft. Years later, his entrepreneurial spirit led him to a short stint in a Seattle business college. But Gorst was soon caught up in gold rush fever and headed north, along with Asahel Curtis and other Port Orchard residents.

As a passenger on the first boat carrying prospectors to Alaska’s Cook Inlet in 1896, Gorst became the first vendor of leather suspenders to the miners. During the trip he sold off the large supply he had brought aboard and arrived in Alaska with his pockets filled with cash. Gorst soon became familiar with the miners and their claims by hauling food, picks and shovels to their camps, charging a dollar a pound, by traversing winter trails on snowshoes, according to Kitsap County Historical Association records.

He also came to share in successful gold discoveries by many of the miners he served. Most notably, he panned gold for Tom S. Lippy’s famous 16 Eldorado claim above Dawson that yielded two million dollars’ worth of the precious metal. When he returned to Seattle, he amused himself by tossing nuggets into the streets to watch newsboys scramble after them.

In 1897, he was among the first gold seekers to climb Chilcoot Pass, a steep climb so exhausting that his grandson, Garry Gorst of Myrtle Point, Ore., marvels at the feats of those miners. He and six other Gorst family members climbed the pass in 2000, during the summer, in his grandfather’s memory.

“They had no Gortex boots, nylon packs and fancy stuff like that. It’s amazing any of them survived the trip. That was really good for me, to see where he’d been,” he said. “He was always a get-out-there-and-do-it kind of a man. As a teen I went deer hunting with him when he was 73, going through a lot of brush. I was calling for rest breaks, not him. I also shared many of his flying trips with him when I was a teenager.”

It was also in 1897 that Gorst, along with four others who spent a lot of time on that rugged incline, spliced climbing lines together to make the first “tram” to carry supplies up the steepest 900 feet of Chilcoot Pass. Later that year he helped other miners rig their supply sleds with sails to help move their food and equipment over snow and ice, ran a dog-sled transportation operation for the Libby claim, and headed the first venture to lead a dozen boats down the Yukon River’s treacherous rapids to reach Dawson that spring.

With the arrival of the new century, Gorst returned to Puget Sound to put his gold earnings to work-in transportation. He began the first motor-launch service between Port Orchard, Bremerton and Mannett, Wash., operating a fleet of three boats as ferries until 1904, when he sold his business and moved to North Bend on the southern Oregon coast.

But that wasn’t the end of the transportation business for Gorst. In 1910, he launched the first auto-stage line in Oregon, between Jacksonville and Medford, adding the first “bus” line between North Bend and Marshfield two years later. In 1913, he started the first auto-stage between Charleston and Bremerton, Wash., and the next year started the first ocean beach route between North Bend and Sunset Bay, connecting with the steamer “Eva” on one of its coastal stops. By 1914 he had launched the first auto-stage between Allegany and Scottsburg, Ore.

Also in 1914, a busy year of firsts for Gorst, he and a partner used an airplane engine and a propeller to make the fastest boat on Coos Bay, then evolved it into the first “air propelled land-and-water machine” to carry freight across Coos Bay and up the beach to the Umpqua River, traveling 70 mph on the beach and 15 mph on the bay. That inspired him to hire a local machine shop to make the first “half-track,” using a Model T Ford for Oregon’s first “sand buggy.”

The next year he started the first municipal “bus” route in Vallejo, Calif., surveyed a route for an auto-stage line from Coos Bay to Crescent City, Calif., then launched a test run, a round-trip with a Fordson tractor pulling a trailer with a mounted car body carrying passengers from Coos Bay to Coquille, Ore.

By 1920, he had created the Coast Auto Lines, with three partners, becoming the first passenger service to connect Coos Bay with Crescent City, Gold Beach, Brookings and Roseburg, Ore., a business later sold to Greyhound Bus Lines. Two years later, he started Motor Coach Co. of Los Angeles, becoming the first service to connect the downtown area with Compton, Long Beach and other California destinations.

If he ever had what people today call spare time, he soon filled it with his latest interest. Several years after leading the wiring of the first multi-party telephone system for his former community in Washington, where Port Orchard is today, he started Oregon’s first trout hatchery in North Bend, in 1919. Years later, in 1938, he became the first to propagate catfish on the Pacific Coast.

But out of all his life’s ventures, it was obvious that it was aviation that truly captured his fascination the most.

Gorst’s interest in aviation began in 1903. At 28, he was fascinated by the Wright brothers’ first powered flight. He followed news of their flying endeavors closely for many years. By 1909, Wilbur Wright was making headlines with his exhibition flights over England and France, while Orville was demonstrating their newest aircraft to government officials in Florida. Gorst was so inspired by those aviation pioneers that he named his son Wilbur.

Many years later, Wilbur authored the definitive record of his father’s exploits, in “Vern C. Gorst, Pioneer and Granddad of United Air Lines.” As he researched the book, his son found a bountiful assortment of accomplishments that revealed Vern Gorst’s pioneering spirit, his love of aviation and his important roles in developing the nation’s air mail and air transport systems.

In 1913, only a decade after the Wright brothers inaugurated powered flight and flying was still the realm of daredevils and barnstormers, Gorst was ready to fly. Since flight schools were scarce, Gorst, at 38, taught himself to fly “a Glenn Martin hydroplane,” lifting off from Oregon’s Coos Bay. Soon afterward, he became the first to advertise passenger flights from North Bend to Marshfield, Ore.

Gorst found that being a pioneer doesn’t always guarantee success. A year later, after the Martin was heavily damaged in a rough landing, his finances forced him to leave aviation pioneering to others for more than a decade. But, in 1925, always eager to fly again, he found new opportunities to take to the air after raising $250,000 to win a bid for the first airmail contract between Seattle and Los Angeles.

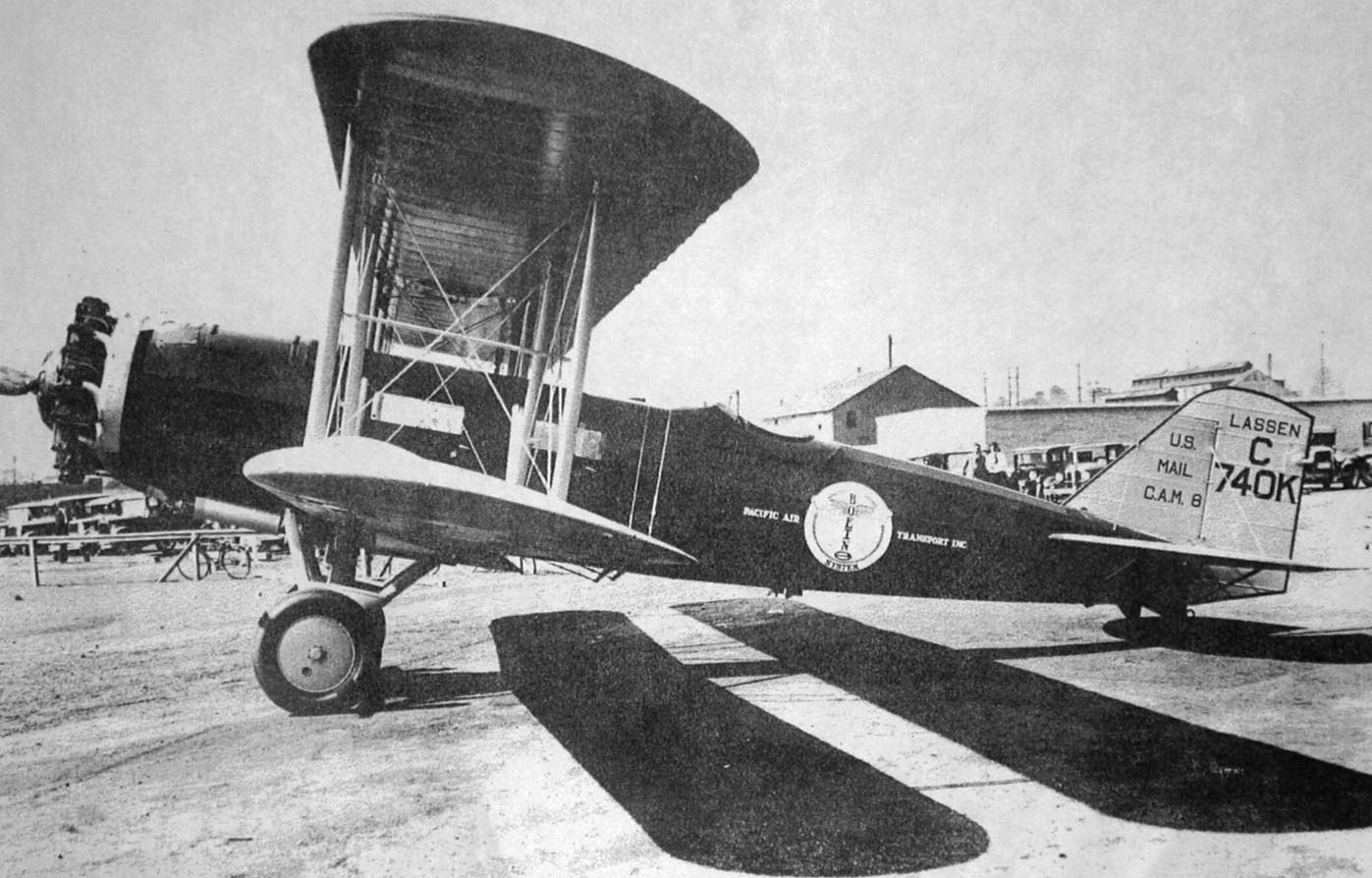

He launched his new business as Pacific Air Transport Co. For $132, a hearty passenger could make the cold, often bumpy and dangerous 1,100-mile, 18-hour trip with Gorst-sitting on mail bags in an open cockpit. And many people did. A shorter segment, Portland to San Francisco, was also popular, taking only six hours compared to 27 hours by train.

Of all of Gorst’s early aviation exploits, creating and running Pacific Air Transport for the first West Coast air mail service was one of the most challenging and exciting for him. He paid his pilots $400 a month, the same as his own pay. He wouldn’t send them on any route he wouldn’t fly himself and took a serious interest in providing the best aircraft he could buy-new Ryan M-1s. His order for 10 of the planes started T. Claude Ryan’s first production line of his monoplane in the United States.

Later, Charles Lindbergh-who often crossed paths with Gorst-told him he chose a Ryan Brougham for his Paris flight after seeing what Gorst had done with them on the rugged flights over the Siskiyou Mountains.

Gorst’s 12 original planes cost him $73,000, with 11 parachutes priced at $3,660 and, of course, there was the need for beacons and landing lights in fields and fairgrounds along the way, at another $19,235.

But flying the early mail routes was always costly in more ways than the initial fleet of planes; it was costly in the deaths of so many pilots who died flying in fog, storms and weather that would have grounded anyone but air mail flyers. To make matters worse, many costly planes were lost when the pilots escaped foul weather by bailing out.

One pilot who left his plane in a dense fog bank north of San Francisco, carrying mail but no passengers, revealed later that his plane “came down by itself with the mail, and would have made a perfect landing had there not been a mound of dirt in the middle of the field.” That made the aircraft cart-wheel “into a total loss.”

In fact, it was the pilots who opposed PAT buying new Fokker Universal, five-place aircraft that helped to meet the growing demand for more passenger seats on the coast route-without having to sit on mail bags. They knew they wouldn’t be able to get out of a tight flying predicament by abandoning the plane if it was filled with people, not just mail sacks, according to Wilbur Gorst’s book on his father’s experiences.

In 1928, to raise money, Gorst sold 73 percent of his successful Pacific Air Transport Co. to Bill Boeing for $94,000, then immediately handed the money back to Boeing to buy one of his new B-1D Flying Boats “for an Alaska mail contract I have in mind.”

In 1929, Gorst began the first air ferry service over Puget Sound between Seattle and Bremerton. A 15-mile trip, it was the shortest airline in the country. That same year, he launched the first commercial flights over the Gulf of Alaska, between Juneau and Cordova, carrying the first airmail letters in that state, along with passengers.

That was also the year his flying service became the first to use beaching ramps on the Seattle and San Francisco waterfronts to load passengers. Later that year, his airline was the first to deliver newspapers to Ketchikan, Alaska, on the same day they were printed in Seattle. A year later he began flying floatplanes filled with eager fishermen into high lakes in the Cascade Mountains east of Seattle.

In 1930, however, the federal government objected to the Seattle company owning not only in Boeing Air Transport and Pacific Air Transport but also Varney Air Lines and National Air Transport. Gorst was the first to propose a solution that found favor with government regulators: merging all four transport services to form United Air Lines.

Despite the benefit of his earlier Alaskan gold, for most of his life Gorst always had more ideas than money and frequently had to search for financing or swap stock in Pacific Air Transport to get operating money or planes. But he never stopped dreaming and launching new ventures.

“He had a great sense of humor, great inventiveness and energy. One of his favorite sayings was, ‘Ain’t we got fun.’ He always had fun at everything he did,” grandson Garry Gorst said. “The government was smaller then; he knew the U.S. Postmaster General and people all along his mail routes.”

Wendy Brady’s mother, Norma, remembers her Uncle Vergne, as she prefers to spell his name, as “a kind, good-looking man with rusty hair and a grin on his face.”

“He was full of ideas, adventuresome and always a favorite at family gatherings,” she said. “When something didn’t work for him he would try another option, never giving up. I’m proud I had the opportunity to go up with him in one of his flying machines.”

Vern Gorst’s love for aviation made flying a part of the Gorst family, too, spanning five generations from Vern to Wilbur, to Garry, a son and a daughter, plus, most recently, the soloing of Garry and Olive’s grandson.

By the time of his death at 77, in 1953, Vern Gorst had lived to see his dreams of air transportation grow into a national network of airlines that changed commerce, the aviation industry and people’s lives, Wilbur Gorst wrote in his book. He closed it by noting that his father’s “remains were flown from Portland to Sacramento, Calif., for interment”-by United Airlines.