![]() By Di Freeze

By Di Freeze

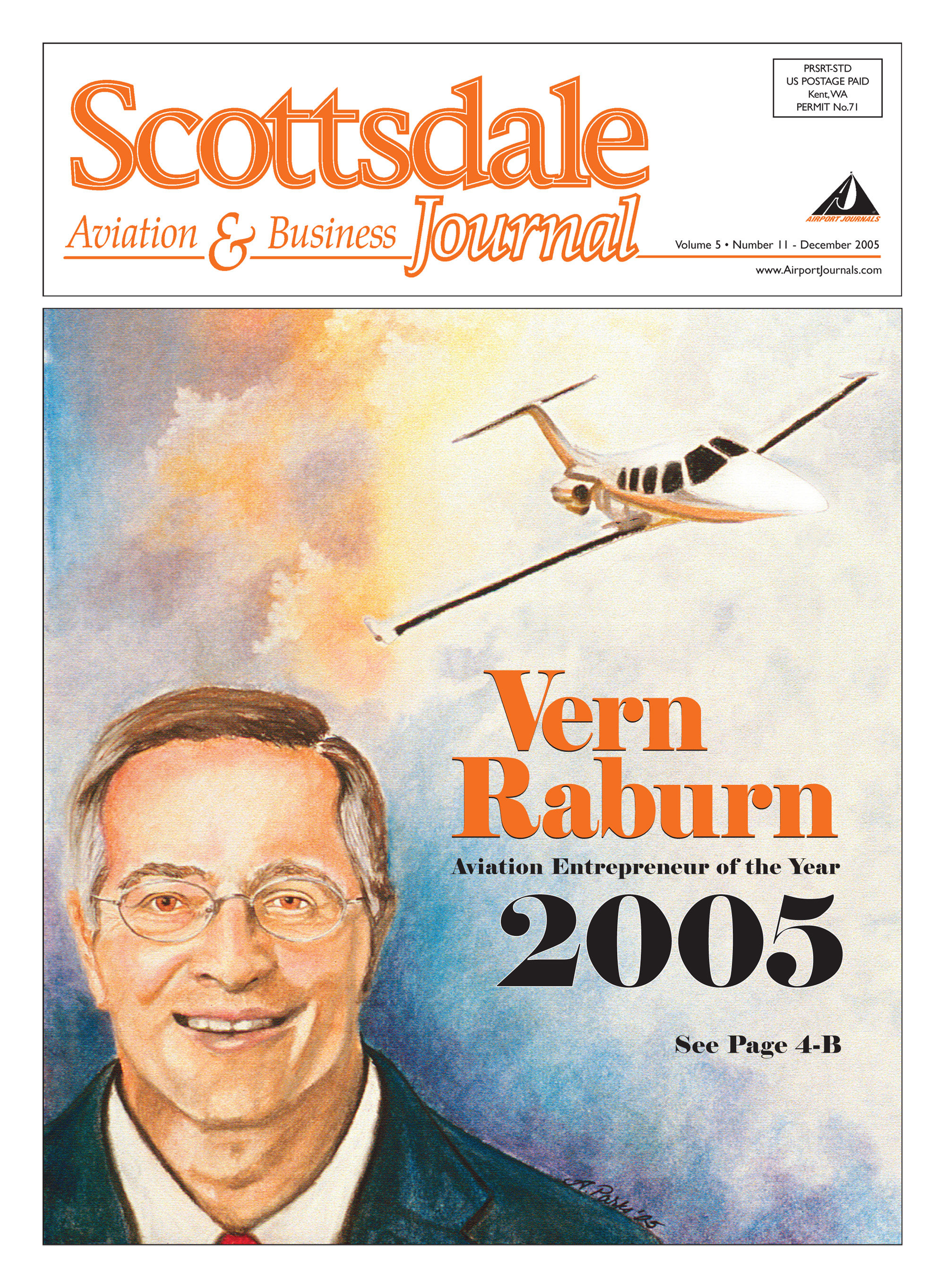

“There’s been no competition in general aviation for a long, long, long, long time,” said Vern Raburn. He’s speaking in past tense, because there seems to be competition now. And Raburn, the “Father of VLJs” and recipient of the 2005 Michael A. Chowdry Aviation Entrepreneur of the Year Award, presented by Airport Journals, is a big reason for that competition.

True entrepreneurs tend to cause changes.

“It always takes some asshole like me to come in and shake things up,” he quips. “It’s always when people and companies come along and say, ‘No, we can do a better job,’ that competition truly sets in.”

Raburn strongly believes that Eclipse Aviation Corporation, the company he founded that is building the revolutionary Eclipse 500, sets an example of taking risks that has changed the way others within the aviation industry are doing business.

“In my mind, there’s no doubt there are aircraft coming into the market today because of Eclipse,” said Raburn, CEO and president. “If we hadn’t done what we’ve done, we’d still be sitting here, looking at exactly the same stuff that we’ve been looking at for the last 50 years.”

Instead, what we’re looking at is an entirely new market, known as very light jets. Within that market are companies such as Eclipse Aviation Corporation, with their Eclipse 500; Adam Aircraft, with the A500; Aviation Technology Group, with the Javelin; as well as more and more companies entering the market.

The skies are alive

Born in 1950, Vern Raburn found his love for aviation while growing up in Oklahoma. His father’s work was partially to blame.

“My dad was chief engineer at Douglas Aircraft in Tulsa, so I was always around airplanes,” he recalled. “He was never a pilot; he wanted to be, but he could never afford it with our traditional family; my mom was always a stay-at-home mom.”

Raburn’s father began working in the space program in 1957, about three months after Sputnik went up, and spent the rest of his career in the program, retiring as the vice president in charge of the Delta missile program.

“He wasn’t directly involved in aircraft, but he worked in the aerospace industry for his entire career,” Raburn said.

His uncle was a flight test engineer for Cessna during WWII.

“There’s one photo in particular in the history books of the UC-78 Bobcat. That’s him in the right seat,” he said proudly.

That uncle would also play a big part in Raburn’s obsession.

“We lived in Tulsa, in eastern Oklahoma, but every summer, my brother and I would stay with my aunt and uncle in the western part of the state,” he said. “They owned a big wheat farm in a little town in Guymon. They were sort of my second set of parents. They had two girls; they would trade kids each summer with my folks.”

It was while staying at that farm that Raburn first flew in an airplane.

“It was on a Central Airlines DC-3,” he said. “That was pretty impressive to a 7-year-old boy. I got to sit on the lap of the pilot and steer the airplane. Of course, this was in the days where the only barrier between the cockpit–as they used to call it–and the cabin was a curtain just hanging there. It was a much more innocent era. Kids weren’t worried about being abducted or molested or anything like that. They were treated as precious things. You got spoiled really fast.”

When Raburn was a little older, he plowed fields for his uncle.

“You’d start out at about 6 in the morning, sitting on a tractor, going three miles an hour up and down a mile-long field, and during the day, there wasn’t anything to look at except the sky,” he said. “The sky, particularly in western Oklahoma, was something that was alive–something that was really fascinating to watch. The morning would be all clear and blue and by noon, you’d have all these little puffy clouds. Then by 3 p.m., you’d have these monster thunderstorms.

“We were on one of the major flyways between the West Coast and the East Coast, so you’d see these Connies and DC-6s flying overhead. Later it was jets. It was just so fascinating to watch the sky do what it did, and to think about those people up there and where they were going. So I fell in love with the sky when I was very young–not even a teenager. Some people like to be around the mountains or the sea. For me, my inspiration was always the sky.”

Raburn’s interest led him to join the Civil Air Patrol when he was 11 years old.

“I think the first time I actually flew an airplane was a Piper Cub that was a Civil Air Patrol airplane when I was about 12,” he said. ”

After his father was transferred to Southern California to work at the Douglas headquarters at Santa Monica, 16-year-old Vern Raburn earned money for flying lessons by mowing lawns and working a paper route. He soloed in a Cessna 150 at Torrance Airport.

A roadblock

He might have made a career early on in the field of aviation, but his eyesight prevented that.

“I’ve worn glasses since I was in sixth or seventh grade, and this was back in the days when all pilots were supermen and didn’t need any kind of assistance,” he said. “I couldn’t get into the Air Force with glasses and I couldn’t get on the airlines with glasses. In those days, it was a hard and fast rule; you just didn’t do anything if you wore glasses.”

That matter combined with the fact that he had a science bent prevented him from ever seriously considering a career as a pilot. Since he loved “tinkering with things,” he logically majored in aeronautical engineering at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo.

“I ended up graduating from Long Beach State, but I did about four years at Cal Poly,” he said. “I was going to graduate in aeronautical engineering, but the year I was going to graduate was the year that billboard went up in Seattle that said, ‘Last one out, turn out the lights.’ So I decided this was a career-limiting move and ended up changing my major to industrial technology, which was more of a cross between technology and marketing.

Raburn, who had been on track to graduate in 1972, instead graduated in 1976.

“I dropped out and started working for the 3M Company,” he said. “I worked for them for about four years and finished up my degree at night.”

In the meantime, Raburn kept flying. The year that he graduated, he opened a computer store. He left 3M, where he had become one of the youngest supervisors in the company’s history, for a variety of reasons.

“As much as I learned and as great a company as 3M is, I had pretty much figured out in a not-too-short period of time that I and big companies just didn’t get along,” he said. “I always had this image that I had the answers to everything and they just sort of ignored me. I felt like I was a little kid sitting there on the hull of the Queen Mary tapping on it with a ball-peen hammer; nobody heard it. And I always wanted my own business.”

At 3M, Raburn had been heavily involved in data processing.

Vern Raburn, recipient of the 2005 Michael A. Chowdry Aviation Entrepreneur of the Year Award, presented by Airport Journals, is a big reason for competition within general aviation today, particularly in the very light jet segment.

“That was purely from the standpoint of getting the data to do my job,” he said. “This was back in the days when everything was filled out on paper and then sent to St. Paul. It was processed and entered–keycards, punch cards, key entry–and then it got sent back. We’d typically get data on what we were doing about six weeks after the end of the month. If we wanted to know how we did in May, it was the middle or end of July before you could answer the question.

“I was pushing the company to do a deployment of minicomputers because this was all main frame-based stuff, but then I started reading articles about microcomputers and decided that was pretty cool. Between the idea that I wanted my own business, and the idea that there were these microcomputers, which I saw as being phenomenally empowering–and the fact that they were just cool because they had flashing lights and switches–I just decided to open a computer store.”

The Byte Shop was formed in Westminster, Calif.

“It was a dealer-type operation–a branded dealer,” he said. “The guy who started it didn’t want to pay the money to go through the franchising process in California, which even then was pretty laborious.”

Eventually, Raburn ended up joining the parent company and becoming general manager.

“At one point, I think we had about 82 dealers under that name,” he recalled. “We became the largest chain of computer stores in the world.”

Microsoft

Following that venture, Raburn was involved briefly in others, including starting one of the first package software companies.

“GRT–Great Records and Tapes–was a music company that decided software had a potential to expand their business,” he said. “I started the software division for GRT.”

Through GRT, Raburn became a customer of Bill Gates, who ended up offering him a job after GRT went bankrupt. Initially, Raburn was president of Microsoft subsidiary Microsoft Consumer Products. Later, he became vice president of the corporation, in charge of all application software. After four years, it was time for Raburn to move on.

“I’m one of those guys that gets bored easily,” he smiled, adding that the rumor has always been that he “can’t keep a job.”

His next move was to Lotus Development, where he served as executive vice president, and then to Symantec, followed by a period as a venture capitalist for a few years, before becoming CEO of Slate Corp. Next, he served as president of Vulcan’s Paul Allen Group until 1997.

“Presently, Vulcan is the overriding company that does everything, but at that time, Paul Allen Group was doing investments principally in technology–things like Direct TV, modems and phones,” he said. “We were trying to do one of the very first Voice over Internet Protocol; we weren’t using the IP, but we were doing Voice over Network (VoN), which would lead to VoIP. We were on the cutting edge of a lot of interesting things.”

Interesting is also how you would describe his flying history. By then, he had already accumulated about 5,000 hours of flight time (he’s logged over 6,000). Eventually, he would have a number of type certificates in aircraft including four-engine airliners and WWII bombers.

“In terms of airliners, it’s the DC series–DC-3, DC-4, DC-6, DC-7,” he said. “Then, the Constellation–the Connies are all the same type rating for all models of Connie. All the Convairs–the 240, 440, 480–Howard 500, Lodestar L-18; those are the primary airliners. In terms of military aircraft, B-25, B-26. I never took my check ride in the B-17, but I’ve flown the B-17 a lot. I’ve flown the B-24 a little bit, but I never really was ready to take a check ride in it.”

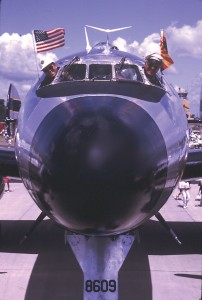

For many years, Raburn owned a Lockheed Constellation that he bought from John Travolta and based in Marana, Ariz., north of Tucson.

“I owned it until about six months ago,” he said. “We finally sold it to Korean Airlines; it’s in a museum in Korea now. I operated the airplane for nearly 15 years; I put just over 2,500 hours on it. We flew it a lot, and never really had a major problem or an incident. It was just getting to the point where both the air show industry here in the United States was not as interested in that, combined with fuel cost and just the difficulty of keeping a very complex airplane like that running. Finally, we found a good home for it. It was a privilege and an honor to be able to fly the airplane for those 15 years. I was one of the four captains on it; I figure we showed it to close to two million people.”

Raburn still has a North American T-6, but says it isn’t licensed, since his latest business is keeping him busy. He also has a Turbo Commander Eclipse Aviation uses as its corporate aircraft.

Eclipse Aviation Corporation

In late 1997, Raburn began working on an aircraft and business concept that would keep his attention for years to come.

“I wrote the business plan in the first half of 1998 and formally started the company that year,” he said of Eclipse Aviation Corporation, based in Albuquerque, N.M.

His day-to-day procedures at Paul Allen Group led to his decision to form Eclipse Aviation.

“While I was working for Paul, a big part of my job was to be on different boards of directors that we had investments in,” he said. “At one point in time, I think I was on 12 or 13 different boards, spread out all over the nation, including places like Ithaca, N.Y., and Lancaster, Penn., in addition to places like Atlanta and Dallas and Minneapolis and Los Angeles.”

At that time, Raburn was living in Arizona and working in Seattle.

“Even though the airline world in ’93, ’94, ’95–which is when a lot of this was going on–was much better than it is now, it still sucked,” he said. “Trying to do all the travel that I had to do was just literally impossible. Getting to Ithaca isn’t the easiest thing in the world to do, and then getting from Ithaca to Lancaster–you can actually drive faster than you can fly, even though it’s an eight-hour drive. There was a lot of demand on my time.”

Raburn and Allen finally decided he needed a better means of transportation, and the company acquired one of the early Citation CJs.

“In the next 22 months, I flew that airplane about 1,000 hours, mostly single pilot–certainly 900 of those hours,” he said. “It became my flying office. I’d flown on corporate jets before, but it was during that period that it became really clear to me that corporate aviation was a phenomenal productivity tool. It was just an amazing way to get around and do business. But it was also phenomenally expensive, even with the CJ being the cheapest airplane that you could buy at that time.”

A CJ, at that point, was about $3.1 million.

“It started out at $2.4 and rapidly escalated to $3.1,” Raburn recalled. “Of course, now a CJ1 is about $4.2 million. I was watching all this and realizing and understanding what a tremendous benefit this whole thing was, but then was running into the pure economic reality of this, and recognizing that it wasn’t accessible to a lot of people.”

Due to his background, interest and desires, Raburn had always studied the innovations of the time. It became clear to him that there was about to be a major change in turbine engines that would lead to a change in aircraft as well.

“I knew, because of my interest in aviation history, that it was always an engine that created the next great opportunity,” he said.

Vern Raburn says the Eclipse 500, pictured on display at the NBAA 58th Annual Meeting & Convention, promises to be the easiest to fly twin-engine aircraft yet built.

Williams International, the leading supplier of small jet engines for the military and commercial markets, headquartered in Walled Lake, Mich., had already won NASA’s General Aviation Propulsion contract with the FJX-2 engine, developed jointly between NASA and Williams. Raburn thought Sam Williams’ engine technology was a “game changer.” Although he thought the engine had great potential, he didn’t feel quite the same about the V-Jet II, a proof of concept aircraft designed by Burt Rutan that served as a platform for the engine. Still, the combination proved a small jet could be built. The V-Jet II and what would become the Eclipse 500 were vastly different.

“Both had two jets on them, and they both were aircraft that weighed less than 6,000 pounds,” Raburn said. “Beyond that, there are no similarities whatsoever. The V-Jet was a composite V-tail aircraft. … The Eclipse is a much more straightforward practical design than what the V-Jet was.”

Due to Raburn’s knowledge of Williams’ FJX-2 GAP engine–which would evolve into the 770-pound-thrust EJ22 fanjet–combined with his personal experience and skill in digital electronics and the belief that it was possible to change how things are manufactured, he came to a conclusion. There was a “real opportunity to really expand corporate aviation and general aviation at the same time.”

“What pilot doesn’t want his or her own jet?” he asks. “All that came together for me in late 1997. I was in the process of starting to really think, because I’d been in the technology business for 20-plus years. That was the beginning of the Internet boom. People like to say that Internet years are like seven years of regular business, so by that designation, I had been working for over 140 years! I just decided that what I really was more interested in was doing something outside of technology for a while.

“That was also in the era when people were out raising two, three, four hundred million dollars to do Internet startups in 60 days. I felt like, ‘Well, the money’s there, and the technology’s there and the right propulsion is there. The opportunity, the market need is certainly there, so why not start an airplane company?’ It was about that sophisticated.”

When Raburn first began telling people about his idea, he said everyone loved it.

“Everybody thought it was very cool,” he said. “Everybody thought we could sell a bunch of airplanes–but they didn’t really want to put any money in it right then. What we ran into on the initial fundraising drive was the belief a lot of people had at that time; it was that they could easily go out and triple their money in 90 days by investing in an Internet company. The money was certainly there, but the competition for the money was very fierce. It was tough from the beginning to raise all the money we needed.”

Raburn needed to convince potential investors that he could create a jet that was affordable, among other benefits.

“It’s the same process that you go through with any startup,” he said. “You have to build up a certain level of credibility with the potential investors, and you have to build that credibility through a plausible, believable business plan that’s grounded in a combination of technology and market. And you have to explain why the current guys haven’t done it and why you think you can do it. There’s no single magic bullet; it’s just a question of how compelling of a story you can present to people.”

Many of Eclipse’s early investors were owners of Challenger, Gulfstream and Lear aircraft. Those pilots, Raburn said, understood the benefit of having a personal jet, as well as the “highly painful” cost of having your own jet.

“We were able to talk to a group of people who fundamentally got it–that if you could build an airplane like this there would be a big market,” he said. “Therefore, the challenge was more about how you could actually convince them that you could build the airplane. Like I said, there’s no one magic bullet; it just requires lots of discussions and persuasion and effort. Ultimately, you can work your way through that, and when you do, guess what? They’ll invest.”

The Williams EJ22 engine was one of the biggest incentives, although there were several.

“We had a relationship with Williams that was exclusive because we were funding a lot of that, so that was the first thing,” Raburn said. “The second thing is that my background in digital electronics was very compelling. We were going to be able to change a lot of the capabilities in aircraft because of digital electronics. Third, we had a lot of good ideas that were very plausible and very defensible in terms of how to change the manufacturing. Fourth, we had a lot of ideas about how to change the business model in terms of capital and in terms of velocity of capital, like doing more of a just-in-time and outsourced approach to manufacturing as opposed to the sort of traditional, vertical integration that, even now, the current general aviation manufacturers are very tied up in. Again, it wasn’t one single thing; it was a whole lot of different things.”

In March 2000, the launching of Eclipse Aviation Corporation was formally announced. The company revealed that the Eclipse 500 aircraft development program was “designed to apply technological breakthroughs in creating a series of safe, reliable, low cost, jet aircraft” that would enable transformation of the U. S. air transportation system. A group of high-technology auto and aerospace executives backed Eclipse with the initial funding of $60 million.

Under their development contract, Williams International was to design and produce the EJ22 turbofan engine (the commercial version of the FJX-2) for Eclipse, and also design, develop and certify both the aircraft and the company’s production facilities.

It was announced that the Eclipse 500, the first in the company’s line of small, highly efficient aircraft, would be a six-place, twin-engine jet. The jet would cruise at 423 mph and have a 41,000-foot service ceiling and a range of 1,800 nautical (2,070 statute) miles.

Built using advanced, high volume manufacturing techniques, with an all glass cockpit, and avionics and operating systems derived from the computer industry, the Eclipse 500 would “transport passengers in automobile-like comfort for a cost that is typically less than that of a full fare commercial airline ticket.”

Through the Eclipse 500, it was said, emerging air-travel services would be able to offer passengers access to 10,000 airports in the U.S. alone, “ushering in an age where point-to-point private jet travel will be available to everyone at affordable prices.” It would be a dramatic departure from the present commercial airline system, which “forces 70 percent of all air travelers to pass through 29 increasingly crowded hub airports.”

The cost of the aircraft in 2000 was projected to be $775,000; commercial deliveries were estimated to begin in 2003.

Air limousines

The Eclipse 500 jet was to be “designed to serve both the existing general aviation market and a new market,” which the company termed the “air limousine” concept.

“Air limo service will be provided by new or current companies utilizing Eclipse’s aircraft to provide air travelers with an alternative for on demand, point-to-point air travel that is fast, convenient and safe,” the company announced. “What the PC did for computing, Eclipse can do for mass-market travel.”

Raburn announced that his company was using “disruptive technologies to drive major change in the way that air transportation works in the United States.”

“The EJ22 engine is just one of three such technologies being deployed by Eclipse,” Raburn said at that time. “We will also use high volume, low cost advanced manufacturing techniques to produce an airframe with vastly superior operating characteristics and extremely low operating costs. The technological leadership of the Eclipse 500 will be further enhanced by a fully integrated digital avionics and operations suite that will greatly enhance safety and reduce pilot load during operations.

090For many years, Vern Raburn owned this Lockheed Constellation he bought from John Travolta and based in Marana, Ariz., north of Tucson.

“In addition to those technologies, we will be applying management principles from the high technology sector, and creating a ‘virtual corporation’ that draws the best skills from wherever they exist and that partners with suppliers and others in the truest sense of the word. The result will be a series of aircraft that are affordable for the individual owner/operator pilot and that will foster the development of a completely new kind of commercial air travel–a limousine of the air.”

NASA Administrator Daniel S. Goldwin enthusiastically embraced the announcement. Goldwin said it signaled “the next step in achieving the vision I set out a few years ago, where safe, affordable, jet-powered small aircraft travel is available to anyone, anytime, anywhere.” He noted that NASA’s budget for fiscal 2001 included funding for the start of a program called Small Air Transportation System, designed to revolutionize U.S. air travel, relying on planes “like the aircraft under development by Eclipse.”

“I believe this will be the first of many entrepreneurial programs resulting from NASA’s investment in general aviation technology,” said Goldin.

Eclipse’s initial board of directors included Chairman Harold Poling, retired chairman and CEO of Ford Motor Company; Dr. Sam Williams, chairman and CEO of Williams International; Kent Kresa, chairman, president and CEO of Northrop Grumman; and Alfred Mann, chairman and CEO of MiniMed. It was announced that Dr. Oliver Masefield, former vice president and member of the executive board and head of research and development at Pilatus Aircraft, would serve as vice president of engineering, and lead the Eclipse 500 development team as a joint employee of Williams International and Eclipse.

Eclipse announced to the world that its goal was to “make it possible for commercial air passengers to move directly between cities on a quick, affordable and convenient basis” and to “allow pilot owners to enter the world of jet-powered aviation.” First commercial delivery of the Eclipse 500 was expected for mid-2003.

Raburn admits he didn’t come up with the “air taxi” or “air limousine” idea.

“The idea was certainly there, whether we knew to call it ‘air taxi’ or something else,” he said. “The simple concept was that if you could get the cost of acquisition and especially the cost of operation down enough and right-size it–meaning not a 10, 15, 20 or 30-passenger airplane–then you could offer an alternate form of transportation, which exists pretty much on the ground, in the form of limos or taxis.”

The entire concept was to basically change aerial transportation from being a scheduled, fixed point to point, aggregated business–“aggregated meaning you fix your schedule and you fix your route so that you can get as many people onto the airplane at once as you can”–to “the opposite concept.”

“Let’s go to a pure point-to-point, and let’s go to on-demand–meaning not-scheduled–and let’s have potentially one passenger per airplane,” he recalled thinking back then. But there were problems with that idea.

“Then you had to compete with the airlines and the pricing that they had,” he said. “When you draw that kind of SWOT–strength, weaknesses, opportunities, threats–type of diagram, you start bounding it by, ‘What are the things you have to meet?” he said. “It needs to be a jet because it needs jet speed and because it brings the highest level of safety. It has to compete with airline fares–not necessarily low-cost carriers like Southwest. At least first class fares. And it has to be able to be economical with just one person, or at the most two people in it.”

Drawing up the boundaries drove them to determine what the airplane would ultimately become. Raburn said once they got to that point, it was still basically “one of those chicken and egg problems.”

“If you have a concept for air taxi, how do you fulfill it?” he recalled thinking. “Well, you can only fulfill it if you have the right airplane. If you have the concept for the airplane, how do you sell enough of them to justify the investment–and ‘believe’ that you can sell enough of them to justify the investment? It’s a very circular process; you ultimately narrow everything down to the point that you have a defensible thesis and a defensible plan.”

Raburn said there were a few people talking about the air taxi idea at the time.

“Bruce Holmes at NASA, and the AGATE Program–this was pre-SATS, and Jim Fallows (author of “Free Flight”),” he said. “The concept of the air taxi has been around probably at least since WWII.”

Although he can’t take credit for the air taxi idea, Raburn says he might agree to being called the “Father of Very Light Jets,” and says that Eclipse coined the term.

“Everybody has to have a handle,” he said. “That’s just the way the world works. People want something to describe something. There were a lot of various terms at that time; microjets was one of the ones that was popular, and it’s still used by a few people. There were personal jets, a play on the personal computer. There were light jets. We came up with very light jets for a couple of reasons.

“The first one was very clear; when you include something like a Lear 40 and a Citation Ultra as a light jet, you can’t get things much more different. The Eclipse 500 grosses less than 6,000 pounds. Those aircraft, in turn, have a different performance level and obviously a different cost. We didn’t think that class of aircraft extended down to this point.”

Raburn said they didn’t like the term “microjets” for two reasons.

“One was the emotional reason,” he said. “We thought it was sort of derogatory or denigrating in terms of the actual size of the aircraft. Second, we actually think there’s going to be another class of jets that are even smaller than VLJs. To some extent, we wanted to reserve microjets for yet another class of aircraft. Not everybody buys that thesis, but that’s our story and we’re sticking to it.”

Preparing for first flight

In May 2002, two years after Eclipse made Albuquerque its corporate headquarters, the EJ22 turbofan engine successfully completed its first flight. It flew for approximately 50 minutes mounted on its flying test bed, a modified Sabreliner Model 60. The engine, weighing approximately 85 pounds, produced 770 pounds of thrust, the highest thrust-to-weight ratio of any commercial turbofan ever produced.

“Each day we draw closer to realizing our dreams of changing the way people travel,” Raburn beamed.

Eclipse Aviation flew its first aircraft, N500EA, on Aug. 26, 2002. Bill Bubb, chief test pilot, piloted the flagship aircraft on its 60-minute flight.

The flight was to begin a 16-month testing program, involving eight test airframes. By September 2002, the Eclipse 500 order book topped 2,000. The Eclipse 500 was originally scheduled to receive FAA type certification in winter 2003/2004, but that plan changed drastically later that year.

In late November 2002, Eclipse announced it had ended its relationship with Williams International, and that Eclipse was in late-stage discussions with two “Fortune 100” engine suppliers, who were competing to replace Williams International as the powerplant supplier for the Eclipse 500.

The relationship ended when it was decided that the EJ22 wasn’t a viable solution for the Eclipse 500 aircraft and that Williams International hadn’t met its contractual obligations. Development of the EJ22 was significantly behind schedule and all analyses indicated it wouldn’t meet requirements.

Raburn said the biggest problem with that situation was that Williams International “refused to acknowledge how badly they had screwed up.”

Vern Raburn sold his Lockheed Constellation to Korean Airlines after operating it for near 15 years, and putting over 2,500 hours on it. It’s now in a museum in Korea.

“When you fail, failure’s not bad in itself,” he said. “I came out of an industry where failure is, in reality, sort of expected. You actually kind of get rewarded for failure. But when you lie about it or when you try to cover it up and you try to claim that it’s not your problem, that’s when problems occur.”

Eclipse’s biggest hurdle, to date, has been the failure of the Williams engine.

“And the biggest victory is the survival of the failure of the Williams engine,” Raburn said. “Most people were pretty much of the assumption that once that engine failed, we were road kill. We were toast. Nothing was ever going to happen. That’s the way it works sometimes. That’s been singularly the biggest issue that we’ve had to overcome–but we’ve had to overcome lots and lots of other issues over time.”

Raburn would overcome the problem by teaming with Pratt & Whitney Canada. Although he described the engine difficulties as “very unfortunate for Eclipse,” he still credits Williams with putting Eclipse on the road to where they are today.

“There’s no question at all that if Williams hadn’t been there with the EJ22, then in all likelihood, this thing would have been stillborn,” he said. “I’ll even go a step further; it’s not clear to me that Pratt & Whitney would’ve gone ahead and made the decision to develop their own engine if Williams hadn’t started development of the EJ22 or the FJ33. Sam Williams deserves credit for having the vision and the ability–frankly, the ability funded by us–to really put together the basic idea of a very small, high-performance turbofan engine that would then enable a new class of aircraft.”

At that point, Eclipse Aviation had already raised $238 million in private equity funding. The Eclipse 500 had been built and all other systems were flight ready, including the avionics and mechanical systems. In addition, the company had received FAA approval on friction stir welding and obtained Organizational Designated Airworthiness Representative status.

“At this point, the engine development program will drive certification timing, and the propulsion system will be our team’s primary focus in the coming months,” he announced. “We’re confident that the new engine selected will result in a better airplane for our customers.”

Pratt & Whitney partnership

Looking back at how far Eclipse has come, Raburn says “building an airplane is just plain tough.”

“It takes an immense amount of capital, effort and people,” he said. “The list of what it requires and takes goes on and on. Did I underestimate the effort that this would take? Yes, I absolutely did. This has ended up being a much, much, much more difficult job than I, in my wildest dreams, ever thought it would be. But that’s OK. Sometimes it’s the journey that’s worth it.”

On Jan. 31, 2003, Raburn vowed that Eclipse would resume flight testing by Dec. 31, 2004, with the Pratt & Whitney Canada PW610F engines. The following month, it was announced that the Eclipse 500 jet would cruise at 375 knots (431 miles per hour), an increase of 20 kts over the previous 355 kts (408 miles per hour) max cruise speed.

Also, ending months of speculation that the price of the Eclipse 500 would move above the $1 million mark, Eclipse confirmed that it would deliver the aircraft at a firm price of $950,000 for customers with non-escrowed deposits and $975,000 for customers whose deposits remain in escrow. Eclipse announced it would deliver its full order book (at the time 2,102 aircraft), at a price tag below $1 million, but said new orders would be priced at $1,175,000.

Eclipse Aviation retired its first test aircraft, N500EA (“Aircraft 100”), in October 2003, after it successfully completed its aggressive 54-hour test program, during 55 flights. The aircraft had been flying with interim engines from Teledyne Continental Motors. Testing confirmed that the Eclipse 500 required no significant redesigns and remained on track for certification in 2006.

Prior to the resumption of Eclipse 500 flight testing, Eclipse devoted significant resources to test systems at the component levels. That proactive approach enabled Eclipse to finalize more than one quarter of all required FAA certification work.

Eclipse manufactured an additional seven preproduction aircraft, including one static test airframe, one fatigue test airframe and five additional flight testing aircraft–N502EA, N503EA, N504EA, N505EA and N506EA. On Dec. 11, 2004, Eclipse Aviation Corporation rolled out its first certification flight test aircraft, Eclipse 500 N503EA. Fully equipped with mechanical systems including pressurization, climate control and ice protection, as well as with the Avio Total Aircraft Integration system, and powered by two PW610F engines, 20 days later, on New Years Eve, N503EA took off from Albuquerque International Sunport for its maiden flight.

With test pilots Bill Bubb and Brian Mathy at the controls, the aircraft completed two flights that day. The first, at 10:16 a.m. (MST), lasted one hour and 29 minutes. The aircraft took off again at 3:59 p.m., for a 54-minute flight. The pilots climbed the aircraft to 16,800 feet and reached 200 knots during the first day of flight tests.

“This is a very important day for aviation and the VLJ market we pioneered,” Raburn said that day. “We are the first manufacturer to fly an FAA conforming VLJ and we’re destined to be the first to certify and deliver this new breed of jet into customers’ hands.”

Raburn recalled that the week leading up to that flight was very laborious.

“It was a tough week, getting the airplane ready for that first flight,” he said. “Everybody just worked their hearts out and worked super, super long hours.”

December 31 was also a rough day.

“We were having some real serious problems with nose wheel shimmy,” he said. “We had hoped to fly a couple of days before that, but the nose wheel shimmy was enough that it was sort of tough. Basically, the crew stayed up all night on December 30, and ended up literally working all night and making some changes.

“We had scheduled a high-speed taxi for first light that morning, since that was December 31. They did the high-speed taxi down the runway and we didn’t have the shimmy. Everybody said, ‘OK, that’s it. Let’s go fly!’ Two hours later, we took off and did the first flight.”

He said that part of the urgency was that everyone wanted to go home for New Year’s Eve.

“It was a great example of how the organization pulled together, and had a real goal–a real objective they wanted to achieve,” he said. “We were able, as a complete organization, to make that all happen. That was a really big triumph, not just because of the airplane flight, but because the company was really able to come together as a team and make this all happen.”

Eclipse today

At this point, Eclipse Aviation has raised about $430 million. By September 2005, the company had five aircraft in active flight testing. Those pilots who put down a deposit on the Eclipse 500 before May 2005 got a deal, because in early May 2005, the company announced a price change for all new orders of the Eclipse 500, from $1,175,000 million to $1,295,000 million.

Raburn is speculating certification in March 2006.

“That’s not a guaranteed date,” Raburn said. “We’re working very hard on that, and we’re very, very close to that. If we don’t hit that date, it’s going to be measured in weeks, not in months, or in quarters. That’s how confident we are.”

Raburn said that as far as development work/testing goes, there’s very little left to do.

“We’ve had the aircraft to its maximum speed (test aircraft N502EA recently achieved a flight test milestone by reaching VD at 452 knots true airspeed) and maximum altitude,” he said. “We’ve done stall. We’ve done water add ice ingestion. We’ve done virtually all of the development testing that needs to be done. Now, we’re doing certification testing. Basically, we’re going to do most of the tests again; but these are all going to be for FAA credit. We’ve done a lot; now, we’re going to do more!”

One problem they’ve had has involved vendors, but Raburn says those problems have mostly been worked out.

“It’s like a roof; if it leaks in one place, you have a problem,” he said. “We still have a couple of problem vendors, and if we don’t make the certification date, it will be because of a vendor. So it’s not a problem on our side, but to some extent, that’s a problem on our side anyway.”

In May 2005, it was reported that Eclipse was about 45 days behind schedule. Raburn said they’ve made up most of that time.

Presently, there are 2,357 orders for the Eclipse 500, including 1,592 firm orders with 765 options. All 2,357 aircraft are secured with nonrefundable deposits. This figure includes two recent Eclipse 500 fleet orders, specifically 30 aircraft by Massachusetts air-taxi operator Linear Air and 50 aircraft by JetSet Air Ltd., UK.

JetComplete Business

Raburn’s excited about JetComplete Business, a version of JetComplete specifically for corporations that operate the aircraft more than individual owners. They announced JetComplete Business at the recent annual NBAA conference. He said JetComplete is an attempt to radically simplify, and at the same time, decrease the cost of ownership of an aircraft.

“It’s the same concept that we’ve had all along, in terms of trying to change the way people own and operate aircraft, and change, if you will, the value proposition of owning and operating aircraft,” he said. “In the case of JetComplete, we’ve taken all the hundreds and hundreds of little pieces of things that as an aircraft owner you have to normally deal with, and we’ve radically simplified things so people don’t have to become systems integrators.

“You want to make sure they can in turn get the most economical advantage from being able to do that. It’s a big integration job. In effect, all you have to do as an aircraft owner is write us one check each month, and it covers everything except fuel and hangars. Insurance, navigation charts, recurrency training, maintenance–scheduled and unscheduled–parts, everything that you need to operate the aircraft.”

The program offers fuel and other discounts as well.

“If you participate in part of this program, we’re able to pull together a high level of volume, which produces exactly what we’ve always said it does, which is a significant discount,” he said. “It’s not that we’ve invented anything new; it’s just that we’re the first ones to take on making all that happen.”

Risk taking

Eclipse also recently brought the world another innovation, PhostrEx, a new fire suppression system.

“This is another example of Eclipse’s willingness to take technical risk to innovate and to improve what we build and reduce the cost of what we build,” he said. “We did that with friction stir welding three years ago. That was one of those things where everybody said, ‘Nah, this will never happen.’ Of course, it has, and now Airbus is using it on the A350.”

Used in production on thin-gauge aircraft aluminum, friction stir welding has replaced many of the rivets on the Eclipse 500, including rivets that would normally be found in the cabin, aft fuselage, wings and engine mounts. The elimination of thousands of rivets dramatically reduces assembly costs and cycle-time production, and ultimately results in better quality joining and stronger, lighter joints.

“We were clearly a pioneer in that, and now the aerospace industry is following our lead,” Raburn said. “PhostrEx is exactly the same thing.”

Raburn said PhostrEx is a completely new approach to fire suppression.

“It’s the first new fire suppression system certified by the FAA in the last 50 years,” he said. “Halon, like Freon, is an ozone depletion gas, so it’s been outlawed since 1988. The last Halon that was manufactured was in January 1994. By treaty–the Montreal Protocol, which is administered under the Clean Air Act–aviation gets to use Halon until there is ‘a viable commercial alternative.’ We’ve already had PhostrEx approved by the EPA as an alternative to Halon. At some point, the EPA will most likely declare that Halon systems have to be eliminated from aircraft.”

Raburn said that presently, PhostrEx is the only alternative to fire suppression that makes sense.

“There’s one other from DuPont; it’s a chemical that typically is about 20 percent less effective than Halon, so you have to carry more of it,” he said. “It’s a very nasty carcinogen, so if you get exposed to it, you’ve got some serious problems. It’s a chemical, but it is a non-ozone-depleting chemical. So from that standpoint, it meets the Montreal Protocol.”

He said PhostrEx, on the other hand, is 10 times more effective than Halon.

“It works ten times faster and requires a tenth of the chemical that Halon requires to put out the same exact fire,” he said. “Combine that with the fact that it’s housed in a low pressure container. So it’s a no maintenance item for ten years. It’s much more effective, and it’s much lighter, because it’s so much more effective. It’s also much cheaper than Halon, and it’s a green gas.

“That’s a perfect example of how Eclipse is willing to take technical risks, to take steps and invest in innovation to produce a much better product while the rest of the aerospace industry sits around and says, ‘Well, that’s the way it always has been, and that’s the way it’s going to be.'”

When it comes to changing the way others do business, Raburn said there’s no doubt in his mind that they’ve even affected large companies like Cessna.

“Cessna is significantly changing the way they do things to absolutely mimic what we’re doing,” Raburn said. “For example, they just announced their training program; it’s exactly like the training program we announced two years ago. And it’s not like their traditional training program at all. Then, Cessna’s now announced they’re putting LED nav lights on the Mustang. That’s the first airplane they’ve put LED lights on. Maybe it has to do with the fact that we put LED lights on.

“There are a lot of things like that. Some of them are really minute details, and some of them are big issues, like training, which is something I’m really proud of. But fundamentally, Eclipse’s willingness to take risk and to invest in innovation–and occasionally fail, by the way, I might add–is nothing but good for the industry.”

Raburn acknowledges fellow entrepreneurs that are also shaking up the aviation industry.

“The other guys who are doing this are Alan and Dale at Cirrus,” he said. “They’ve done a wonderful job, and they’ve taken it right to Cessna. To be very blunt, do you think Cessna would have ever put the G1000 (Garmin integrated avionics suite) in the 172 and 182 if Cirrus hadn’t made glass standard in the SR20 and SR22 two years ago?

“They’re doing exactly the same thing in the single-engine piston market that we’re doing in the corporate jet market. Competition is good! It’s tough sometimes, but competition is really, really, really good. At Eclipse, we take risk, we innovate, and we try, as a result, to really push the envelope. Sometimes we fail, but most of the time, we succeed.”

There are many aviators of the past Raburn looks to when it comes to inspiration, including Bill Lear, Walter Beech and Clyde Cessna.

“And guys like Kelly Johnson, who was so innovative in things like the SR-71 or the Lockheed Constellation, and Donald Douglas and other innovators like C.R. Smith, president of American Airlines, who basically designed the DC-3,” he said. “And then Jack Frye at TWA and Charles Lindbergh, who was the technical advisor. There are a lot of really smart, risk-taking, inspirational people in the history of aviation. But it’s hard to find many guys like that in the last three or four decades. I’m sure I’m shortchanging somebody. Roy LoPresti was a very innovative guy, and Ed Swearingen. Of course, Bill Lear, with the Lear in the 1960s, and then the Challenger was basically his idea.”

The future

Raburn is sticking to his belief that the Eclipse 500 promises to be the easiest to fly twin-engine aircraft yet built.

“I’m more sure of that statement than I’ve ever been,” he said. “I’m rated in the airplane now, and I have about 20 hours already in it. We have over 600 hours total. People are flying the airplane who’ve never flown it before–like Tom Haynes from AOPA Pilot and Fred George from BCA–and raving about how easy the airplane is to fly.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that not only are we going to have an aircraft that is significantly easier to fly, but it’s also going to be significantly safer to fly. And people haven’t seen the full story yet; when both Fred and Tom flew it, we didn’t have the final loads of software and all the final capability in terms of system. What they saw was the pure handling characteristics of the aircraft, which blew them away. But what they haven’t seen yet–as most people haven’t–is the fully integrated system and how easy it is to fly and manage the aircraft from that standpoint.”

Raburn got his rating in the Eclipse 500 in early October. When asked if there were any squeamish board members who preferred that the founder stay out of the cockpit, he said denying him that pleasure wasn’t an option. In that matter, he turned to Grace Hopper, the first female admiral in the Navy (who was also involved in building the first digital computer), for guidance.

“She always used to say, ‘It’s far, far better to beg for forgiveness than to ask for permission,'” he laughed. “I work on that basis. I didn’t ask for permission to go fly the airplane; I just did it. After all, I am president, even though I report to a board.”

- Vern Raburn’s extensive amount of traveling with the Paul Allen Group eventually led him to form Eclipse Aviation Corporation, the manufacturer of the Eclipse 500.

- Bill Bubb, Eclipse Aviation chief test pilot, piloted the flagship Eclipse 500, N500EAA, on its maiden flight on Aug. 26, 2002.

- Vern Raburn, shown with EAA President Tom Poberezny during EAA AirVenture 2005, speculates certification in March 2006 for the Eclipse 500.

- Vern Raburn says Eclipse Aviation Corporation sets an example of taking risks that has changed the way others within the aviation industry are doing business.