By Di Freeze

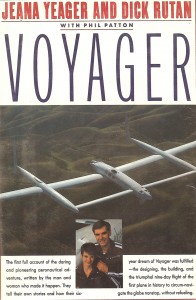

“Voyager” tells the story of Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager’s quest to fly nonstop and un-fueled flight around the world, in an aircraft designed by Burt Rutan.

“Voyager” tells the story of Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager’s quest to fly nonstop and un-fueled flight around the world, in an aircraft designed by Burt Rutan.

As a group of people talked over coffee at the Mojave Inn, in Mojave, Calif., in late 1980, Burt Rutan doodled on a napkin something that seemed like a “crazy,” yet bizarrely feasible dream. Could someone fly around the world on one tank of gas, nonstop?

His older brother, Dick Rutan, was skeptical at first, but Jeana Yeager couldn’t think of a reason why not. After more thought, the answer seemed to be “yes,” if certain conditions were met. The aircraft could be designed with carbon fiber, making the craft half the weight and five times stronger than steel. It would be the largest composite aircraft ever built.

“Burt realized that a trans-global flight, un-refueled, without stopping, was one of the last major milestones to be recognized as a significant event in aviation,” Rutan said.

As they continued to talk, the innovative designer sketched an airplane that looked like a giant wing. It seemed evident that the wingspan would need to be as big as a football field, the gas tank as big as a lake, and the crew, the weight and size of children.

Dick Rutan had the utmost faith in his younger brother, and in himself. Of course, he wanted to be the pilot.

“Once Burt thought it could be done, we became wholly enthralled in the entire thing,” he said. “There wasn’t anything else that I wanted to do—until we got it done.”

Yeager felt the same way. She also knew that if she was involved, the “weight” of the crew shouldn’t be a problem.

Jeana Yeager

Jeana Yeager, 28, weighed only 95 pounds.

Born on May 18, 1952, in Fort Worth, Texas, she grew up around horses, and was passionate about them. Her family relocated between Texas and California a couple of times while she was a child. When she was old enough to be on her own, she moved to Santa Rosa, Calif., in 1977, where she worked as a draftsman and surveyor for a geothermal energy company.

An early fascination with helicopters (which reminded her of dragonflies) led her to want to fly. She earned her fixed wing license in 1978.

During that time, she met Capt. Bob Truax, a rocket scientist who offered her a job working at Project Private Enterprise, which sought to develop a reusable spacecraft.

At an air show in Chino, Calif., in 1980, Yeager visited the Rutan Aircraft display, where she met the Rutan brothers. She and Dick Rutan instantly hit it off, and she was soon visiting Mojave regularly, before moving there.

The couple was discussing forming their own company, until the subject of flying around the world came up. Now, she quickly volunteered to ride along with her “cowboy.”

Why should she have any qualms?

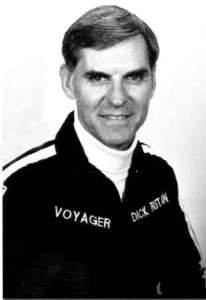

Dick Rutan

Dick Rutan says he’s “always wanted to see what’s on the other side.”

“I’m mad because I wasn’t part of the Lewis and Clark expedition,” he said. “The quest to do something nobody had ever done before. The voyage of discovery. They found things that no European had ever seen before. They opened up the rest of our country. It was phenomenal.”

Rutan was born July 1, 1938, to George and Irene Rutan, in Loma Linda, Calif.

“I never spent a minute there that I can remember,” he said. “I grew up in Dinuba, California.”

Rutan and his younger brother shared a main interest.

“My brother and I both had an abnormal fascination for airplanes from the moment of birth,” he said. “We lived, breathed and talked nothing but aviation and airplanes. But he was more interested in the design of the airplane.”

Irene Rutan was very supportive of the interests of her boys, who were five years apart.

“She would take us to the military open houses and fly-ins,” Rutan said. “That maintained the interest in aviation. When I started taking lessons, when I was 15 years old, my dad got interested. He went ahead and got his license and actually had an airplane.”

George Rutan first bought a Cessna 140.

“Then he and two other doctors went together and bought a Beechcraft Bonanza that we flew for a while,” he said.

Rutan was a high school sophomore when he first saw the Air Force’s new fighter, the F-100 Super Sabre. At that moment, he decided he would fly one.

He began taking flying lessons when he was 15 and soloed after training for only five and a half hours.

“The soonest you can solo an airplane is when you’re 16 years old,” he said. “On the morning of my 16th birthday, the very instant I was legally able, I went out and made my first solo flight.”

After retiring from the military, Lt. Col. Dick Rutan (front) went to work with his brother, Burt Rutan (backseat) at Rutan Aircraft Company, at Mojave Airport, as chief test pilot and production manager.

He went on to earn commercial, instrument, multiengine, seaplane and instructor certificates.

After high school, the brothers followed their separate interests.

“Burt went off to engineer airplane design school and I went to the military, to fly high-performance jet fighters,” Rutan said.

He’d have a little wait before doing that, however. At 19, he signed on with the Air Force Aviation Cadet program, but when he didn’t do well enough on a written test to qualify for a pilot slot, he signed on as a navigator. Nearly seven years passed before he was able to get into pilot training.

While waiting to report to the military, he attended Reedley Junior College, a few miles from Dinuba, where he worked with aircraft engines toward getting an official Federal Aviation Agency power plant license.

He reported to Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio for preflight, and then went on to Harlingen, Texas, for navigator school. He finished at the top of the radar and celestial navigation class.

Rutan was assigned to Waco, Texas, for radar intercept officer training. He trained in the backseat of a fighter interceptor. Assigned to Keflavik, Iceland, in 1961, he flew the last active air defense scramble in an F-89 Scorpion.

As a navigator on C-124 Globemaster transports, stationed at Travis Air Force Base, Calif., Rutan first flew into Southeast Asia at the beginning of the Vietnam War buildup. In 1966, when two F-100 slots opened up, Rutan, at the top of the class, got first pick. He went on to F-100 gunnery school at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona. In 1967, he went to Vietnam with his gunnery class.

“I was a nuclear strike pilot,” he said. “I had a one megaton thermonuclear bomb that was assigned to me, to go and hit a target in the part of the Communist domain for a number of years.”

Rutan flew 325 combat missions.

“I flew 105 in North Vietnam,” he said. “We called it “out of country.”

He volunteered for an outfit called Commando Sabre—call sign “Misty”—whose pilots flew spotting missions over North Vietnam. Forward air controllers usually flew in Cessna Birddogs, finding targets for fighter bombers. But over the north, those planes wouldn’t survive the ground fire, so they used F-100s instead, evoking the term “fast FACs.” Rutan flew two tours as Fast FAC.

“It was a little outfit on the base,” he said. “Three squadrons there flew close air support, in support of ground troops in South Vietnam. We’d go with bombs and rockets to help the ground troops. But this was different. We had a small cadre of airplanes. We had almost the highest loss rate of any other outfit there. We lost a lot of people and a lot of airplanes. It was high risk, but I guess they figured what we were doing was worth it, because we would find a lot of things on the Ho Chi Minh trail. The missions were exciting, and very long, at low altitude.”

Rutan and his team flew over North Vietnam and Laos, looking for convoys, antiaircraft sites, supply depots, staging areas and transshipment points. When they spotted any of those targets, they marked them with smoke rockets.

“We would find targets and direct other fire bombers in on them,” he said.

Most pilots did one 120-day tour with the Mistys. Rutan volunteered for a second and then a third. That ended abruptly one day.

“I got shot down just about the beginning of my third tour,” he said.

Rutan was shot down in August 1968, over North Vietnam.

“I was hit numerous times,” he said. “But this one was a more fatal hit for an F-100, and I hit the bailout.”

On the final mission of his seatmate’s tour, they were strafing too low and took ground fire. With the plane burning, they reached the coast, just as the engine quit. They glided down and out over the water, and ejected. They were picked up three and a half hours later.

“They try to get you as soon as they can,” he said. “The longer you stay up there, the less your chances are of returning.”

At that time, Rutan had more combat time over North Vietnam than any other pilot.

“This was all a high-risk volunteer thing,” he said. “I had two volunteers, working on my third. I was about ready to rotate home anyway. I told them, ‘My combat’s over. I think I’ve done my fair share.’ They agreed.”

Lt. Col. Rutan was awarded the Silver Star (“Gallantry in Action”), five Distinguished Flying Crosses, 16 Air Medals and a Purple Heart.

“The people that flew those high-risk missions were relatively highly decorated, and rightfully so,” he said. “The exposure, loss rates and amount of danger were quantum amounts above anybody else that flew up there. We were down amongst them, at low altitude. The regular fighter bomber guys would come in at real high altitude, drop their bombs and leave quickly. They wouldn’t even be “in country” more than five minutes. We spent four, five and six hours a day up there in low altitude.”

Rutan rotated to Europe.

“I was assigned consecutive overseas tours from Vietnam to an accompanied tour to Lakenheath, England, 60 miles north of London,” he said. “My second daughter was born in Lakenheath. I flew there in support of the Cold War activity and NATO operations for four years.”

Voyager pilot Dick Rutan “had an abnormal fascination for airplanes from the moment of birth.” That passion led him to the military and to Vietnam, where he flew 325 combat missions.

Rutan went down again when an airplane he was flying had a mechanical malfunction.

“I had to eject just before I landed there at Lakenheath one rainy afternoon,” he said. “I ejected real low and the parachute opened and I went directly into the trees. I just barely made it. It was real close to the air base, so they just came out and got me.”

Later assignments took him to northern Italy and Turkey. He also had a headquarter staff job at Wright-Patterson, Dayton, Ohio, for three years. He spent another three years at Davis-Monthan, in Tucson, Ariz., as a flight test maintenance officer of the 355th Tactical Air Command squadron.

In 1978, with 20 years in the military, the 39-year-old retired.

“That year, I joined my brother in Mojave,” he said.

Rutan had already done test-flying on the VariEze prototype. He had flown it to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh in 1975, setting a closed-course distance record. He now came to work at RAF as chief test pilot and production manager. He tested new planes, put them through their first flights, tracked their performance and helped with improvements.

“I flew a Microlite for the European market, designed for Colin Chapman,” he said. “I flew a prototype we did for an Air Force primary trainer replacement for the T-37 by Fairchild, and I was the primary test pilot on the Beechcraft Starship.”

He test-flew the Next Generation Trainer, the Long-EZ, the Defiant and the Vantage. He held several records in EZs and flew aerobatic exhibitions. And, he had come to feel that his talents were being wasted.

We can build it

When Burt Rutan asked who would build the aircraft, Dick Rutan responded that he and Yeager would. But it would take time and lots of money. Knowing the government wouldn’t fund the project, they’d need to raise the money through private support.

Yeager would eventually come up with the aircraft’s name. “Going where no man had gone before” had always appealed to Rutan, so he thought Voyager was appropriate.

The Federation Aeronautique Internationale established that the minimum distance to qualify for a world flight had to be the distance of the Tropic of Cancer or Capricorn, equal to 22,858 statute miles. The first nonstop around-the-world flight was made during a U.S. Air Force demonstration, but the aircraft was refueled in flight. In 1949, the B-50 Lucky Lady II made the trip in 93 hours. Voyager’s aim was to break the record of a Boeing B-52, flown by an Air Force crew, which flew without refueling 12,532 miles in 1962.

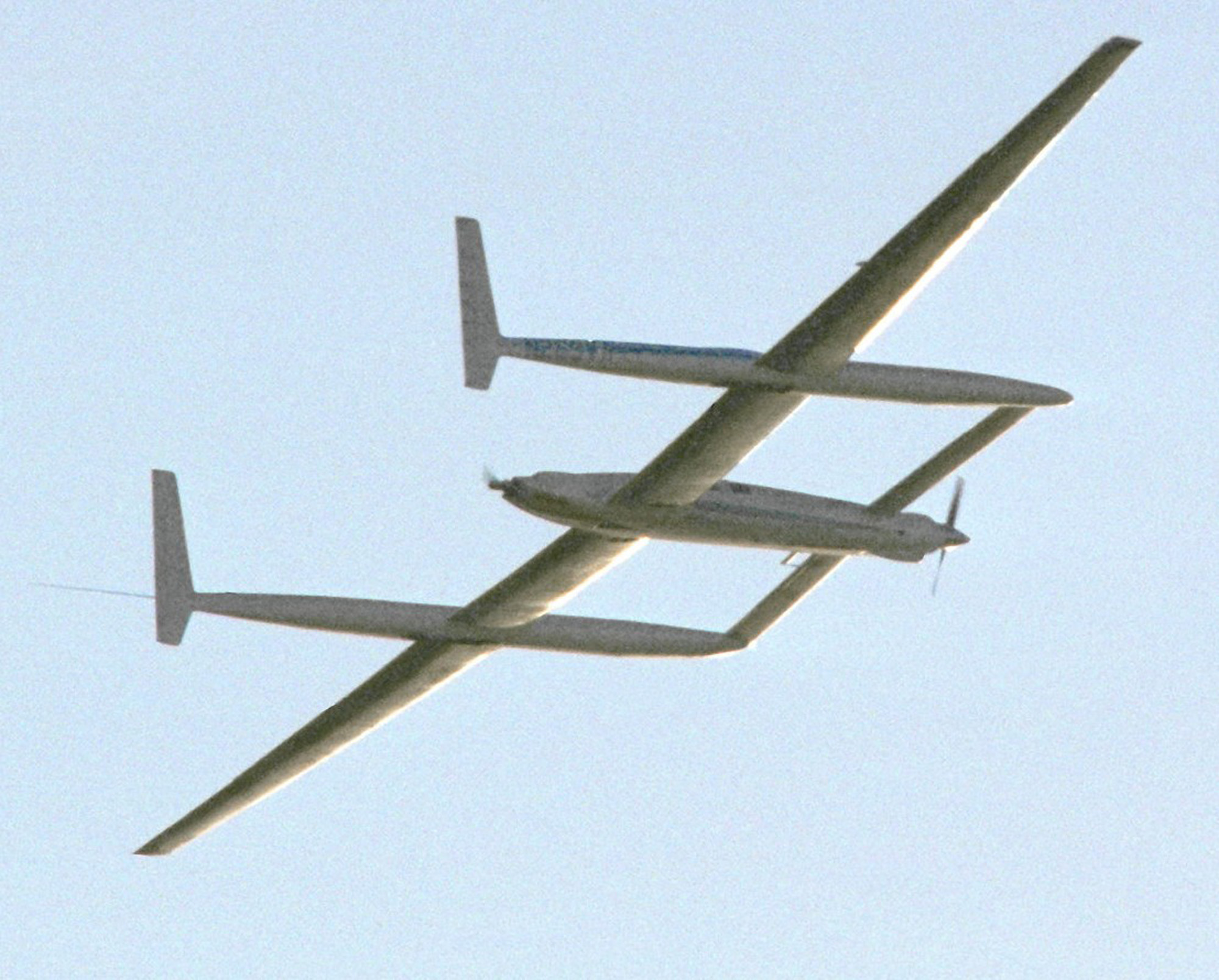

The designer pictured the aircraft initially as a single, large wing, fronted with another tiny wing, or canard. Eventually, his thoughts turned to twin booms or outriggers. When he sketched his design, Voyager looked like a catamaran sailboat crossed with a glider, and not unlike a fragile UFO.

By March 1981, sketches of the canard showed a natural brace for the twin booms. It canted back in a slight sweep to attach behind the front engine. The vertical stabilizers moved from the wings to the rear of the boom tanks.

Voyager’s wing, resembling an oversized sailplane wing, was longer than a 727 jet airliner’s. Voyager would have engines on the front and rear of the fuselage. Two engines would be needed for takeoff and climb. For more efficiency, the front one was to be turned off while cruising.

Designed for maximum fuel efficiency, Voyager wouldn’t have interior tanks used in traditional aircraft design. It was virtually a flying fuel tank. Sixteen fuel tanks in the wings and fuselage fed into a common fuselage feed tank. The bulk of the weight was to be fuel. The twin boom shape cleverly distributed that weight evenly along the wings. Keeping weight down was imperative: for every pound added to the 939 pounds of basic fuselage and wing, six more pounds of gasoline would be required. Tiny winglets at the end of each long, thin wing raised the fuel vent from the three outboard wing tanks high enough to keep the fuel from draining out onto the ground.

Eventually, Voyager’s wingspan would be 110 ft., 8 in.; length, 29 ft., 2 in.; and height, 10 ft., 3 in.

Frustrations

Yeager organized and ran Voyager Aircraft Inc. She also designed a paint scheme and a logo, an angular series of Vs that fanned out like a wing.

After setting up their corporation, Rutan and Yeager spent 18 months drafting a proposal and circulating it among potential backers. More than $2 million would be needed for the flight.

“We spent the first year and a half trying to find a sponsor,” Rutan said. “We knew it was going to be an expensive program and we had no money. The $10,000 that Jeana and I had between us was expended trying to find the money to do the project.”

They traveled air show circuits on weekends, taking along Voyager memorabilia. At first, they flew Burt Rutan’s Long-EZ prototype. But he wasn’t thrilled that his brother hot-rodded the plane, and was concerned that pilots watching could be killed while trying to copy the dangerous moves his fighter-pilot brother performed flawlessly. Dick Rutan didn’t think that craft needed to be handled like a Piper Cub.

When the owner stopped letting his brother fly his Long-EZ, Rutan and Yeager scraped together enough money and put together their own Long-EZ. Both would set records in the aircraft.

When they began looking for financing, some potential investors thought their plan was too ambitious, while some thought a flight around the world was unnecessary, since it had been done before.

“We’re going all the way around on a single fill-up,” Rutan clarified.

Jeana Yeager met Burt and Dick Rutan at an air show in 1980. That same year, she enthusiastically agreed to be part of a team intent on flying around the world in an experimental aircraft she named Voyager.

But when it was discovered that the trip would be made in a homebuilt aircraft, it raised eyebrows. Burt Rutan had carefully detailed designs and specifications, but no major industry sponsorship had presented itself.

Ross Perot, the Texas computer magnate, frankly told the couple that sponsoring the project might open him up to criticism by his liberal enemies, since they weren’t married. He also advised that they’d have a hard time finding sponsors until they had something concrete people could see or touch. Even then, sponsors might be afraid of the aircraft coming to misfortune, while bearing a sponsor’s logo.

Yeager and Rutan considered Japanese support, but believed a Japanese-supported airplane would never hang in the Smithsonian. Sponsorship emerged from within the tobacco industry, but they loathed tobacco, and didn’t think smaller supporters would appreciate the cigarette decals either.

“We just couldn’t find a sponsor,” Rutan said. “We didn’t let that dissuade us. We said, ‘Well, we’ll do it without a damn sponsor.’ It’s much more difficult when you have to beg for all the materials, scrape and spend most of your time trying to stay alive, day to day. Keep the volunteers working and find materials for them. So it drew the project out for quite a long time.”

They would build the airplane themselves, in the RAF shop, using materials they could scavenge from friends in the homebuilt supply business.

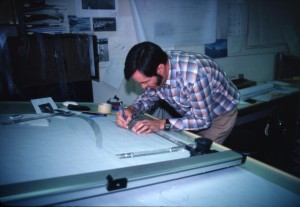

Rutan spent most of his time working on the airplane in the hangar and trying to round up equipment. As they worked on Voyager, curious people began drifting by the hangar at Mojave Airport (MHV), to see how they were progressing.

“The word got around, and talented people just showed up at our door,” Rutan said. “Had they not showed up, we couldn’t have made it around the world. It was that kind of environment.”

One of those people was Bruce Evans, who asked if they needed help. Evans, who had composite material experience, was formally hired as a contract consultant to build Voyager. He became the crew chief, the first official member of the team. Other volunteers included Mike Melvill, an employee of Burt Rutan’s newly formed Scaled Composites LLC (which would build composite partial-scale prototypes of aircraft for manufacturers) and his wife Sally.

The generosity of volunteers amazed Dick Rutan, who equated their work to the pioneer days and “grass-roots barn-raising.” Also, enthusiastic “plain folk” contributed loose change and a few dollars here and there.

They started building Voyager in the spring of 1982. To have a structural weight of less than a thousand pounds, the aircraft used lightweight composite materials in 98 percent of its structure. It was designed out of paper-thin sheets of carbon fibers, laid over a sandwiched layer of Nomex honeycomb (a resin-impregnated paper that resembled the bee’s product) surrounded by two layers of carbon filter cloth imbued with epoxies. Graphite fiber, half the weight of steel and five times as strong, provided strength, flexibility and lightness.

“Hercules provided the carbon fiber,” Rutan said.

Hercules also provided two technicians and their 40-foot autoclave, the high-pressure oven that was crucial for fabricating the spars and other parts.

After some complications, the team was able to cure, cool and release their first working part, at the end of December 1982.

Power

For the project, Burt employed “engine staging.” One engine would be turned off after takeoff. That engine would be restarted when necessary—to climb or if the other engine presented a problem.

They conducted test flights with old Lycomings that had been used on the Long-EZ. For the ultimate flight, though, they needed engines that burned little fuel and would be efficient at low power settings during long stretches, when relatively light or in slow flight.

They chose to use Teledyne Continental’s new IOL 200 liquid-cooled engine as their main cruise engine on the back, and a 0-240-a standard air-cooled engine on the front. Their plan was to have to start the rear engine only once (by hand). Although the engines provided less horsepower, they allowed for better fuel economy than originally planned. Instead of eleven or twelve thousand pounds, they could take off at nine or ten thousand.

Conflicts

Rutan looked at his brother as the “genius designer.” Still, he didn’t always agree with his designs.

“I look at all of his stuff and I tell him, ‘It won’t work.’ But it generally always does,” he said. “We have this agreement: I’ll never claim to be a genius designer and he won’t ever claim to be a hero pilot.”

Conflicts did often arise between the brothers regarding Voyager. The designer was trying to keep weight to a minimum and believed they must survive with a minimal amount of “high-tech bells and whistles.” Every added item meant more fuel would be necessary.

Dick Rutan disagreed, insisting radar shouldn’t be grouped in the category of gadgets. His brother had flown for years without radar, and reminded him they’d have the assistance of ground mission control.

But Rutan and Yeager didn’t want to fly across the Pacific Ocean without radar in an airplane as “light and vulnerable” as Voyager.

“I’ll be damned if I’m going to drive blind across an ocean,” Dick Rutan adamantly argued.

In that instance, the designer relented.

The long journey

Burt Rutan created the Rutan Aircraft Factory in the Mojave Desert in 1974, six years before he began designing Voyager.

All of 1983 would be devoted to construction. By fall, they began to put parts together, and the shape of the airplane gradually began to emerge. In 1984, after outgrowing the back room at RAF, Hangar 77 at Mojave became Voyager’s home.

In April 1984, 17 months after they began to build Voyager, completion of the airplane was in sight. Yeager, who organized and ran the office, kept pushing an idea she had.

“Jeana came up with a thing called the VIP Club: Voyager Impressive People,” Rutan said. “If you wanted to join our club, it was a $100 contribution to the project. The only thing we had to offer them was a confidential newsletter. They’d find out things before anybody else did. And we’d carry their name around the world in a logbook and give it to the Smithsonian, when we put the airplane in the museum just after the flight.”

Yeager was convinced the club would create wider, grass-roots involvement and interest, and convinced the brothers to give it a try. The program was so successful, it became the major source of money to build, test and fly the aircraft.

By May 1984, the pieces were mostly assembled, and the fuselage, wings and cowlings all together on the gear, ready for paint.

Voyager takes flight

Dick Rutan took Voyager for her maiden flight on June 22, 1984. For the 40-minute test flight, he flew with only a fraction of the aircraft’s fuel capacity.

When Mike Melvill, flying the chase airplane, slid underneath Voyager, he found an oil leak. Rutan shut off the front engine, and went on with the test flight.

That flight taught them that the handling was marginal, the plane was sensitive in pitch, the aileron forces were heavy, the roll was slow, the rudder was barely adequate and the elevator forces were too light.

“Airplanes that fly nice have big tails and big rudders, but that just hurts their range,” Rutan said. “On Voyager, all that had to be as small as possible; that made the airplane virtually uncontrollable. Then, we took a lot of the structure of the airplane away, to turn that into fuel. It was very unique and optimized for range, nothing else. So the airplane was very weak and frail. It didn’t have flaps or fancy landing gears. To achieve extraordinary range, it was really minimal.”

Voyager had flown, though.

Those involved celebrated that evening. Then, it was back to work.

On the second flight, Rutan ran into some thermals and was alarmed to see the wings flailing. Turbulence caused the wingtips to flex and bend; when that happened, the aircraft intermittently sank and climbed. Yeager, along on the flight, was reminded of being on a sailboat, rocking and rolling on the ocean. For the first time ever, she knew how it felt to be seasick.

The long, thin wings were designed to move up or down as much as 30 feet and could take tremendous stress, but the team feared the wings could oscillate too much and snap off. Dick Rutan had a simple solution for the dilemma: he wouldn’t look at the wingtips when they began to move up and down.

Voyager left a lot to be desired, as far as creature comforts were concerned. The cabin and cockpit were side by side within the fuselage. The crew’s living quarters resembled a horizontal phone booth.

Like jet fighters or the Long-EZ, Voyager was a side-stick controller. The pilot seat was on the right. The seat and stick were set close to the right side wall, to leave space for the off-duty pilot to stretch out along the left-hand side of the cockpit.

The pilot controlled the plane from a seat on the floor. To accommodate Rutan’s frame, the contoured, articulated seat was so low that Yeager had to place both hands on the armrests and lift herself up about a foot, in order to see out the canopy.

The pilot slipped the seat all the way back, and then slid to the left, head to the back, for the other crew member to climb over the pilot’s legs and into the seat.

When not in the pilot’s seat, because of her backpack parachute, Yeager had to raise her head to look forward at the panel, and turn on her side to watch Rutan.

The aircraft had no windshield, and windows were another problem. While lying down, they were too high to look out of, and when Yeager was in the pilot’s seat, they were too low.

Oshkosh

Although problems continued to crop up, Yeager and Rutan were tempted to fly Voyager to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh in Wisconsin in August 1984. It was important to make the trip, to keep interest in the project.

Problems plagued their attempt to fly to Oshkosh. Things began to go wrong even before they got to the other side of the Antelope Valley. The rudder autopilot servo broke loose from its bracket on the floor, and then two bottles of glue popped open in the storage area, producing nauseating fumes that burned their eyes.

The crew decided to turn back. On the way back to Mojave, they ran into convective activity and rain showers. Rutan had been afraid that Voyager, like other canard aircraft, might have trouble with rain cutting lift on the canard by disturbing laminar flow. As they started picking up the first few drops of rain, the airplane started to pitch down. Rutan corrected with more elevator, but it kept coming down.

Voyager was virtually a flying fuel tank. Sixteen fuel tanks in the wings and fuselage fed into a common fuselage feed tank.

Even as he pushed the power up, they were going down steeply, but they pressed through the rain. After the canard started to dry off, they turned, flew around the shower and landed at Mojave.

They fixed the servo and cleaned up the glue. Upon the designer’s suggestion, Yeager sanded the canard to rough it up. The next day, they set out again. As before, they encountered convection and showers.

Picking their way through the mountain passes of the Rockies in thunderstorms wasn’t easy. If they could climb 3,000 more feet, they could get above much of the turbulence, but 15,000 feet meant they needed oxygen, and they hadn’t brought any along. During the afternoon, tremendous thermals caused by heat rattled Voyager over the plains.

Her crew wasn’t faring well. Rutan had hand-flown the aircraft most of the day and was exhausted. Yeager felt seasick and had a bad headache.

They lasted 11 hours in the cabin they had begun calling the “torture chamber,” before landing in Salina, Kansas, just before sunset. Frustrated and beat, Rutan, who admitted that Voyager was the only plane he’d ever feared, vowed he never wanted to see the craft again. The critics were right; they had made a suicide pact. Taking the train home sounded ideal.

Realistically, though, the problems could be solved. The flight made them aware that they had to try to stay out of turbulence, and that they definitely needed radar to avoid storms.

Things looked different the next morning, once Rutan’s nerves had calmed. They got in the aircraft, and again headed toward their destination. When they did arrive at Oshkosh, a quarter of a million people cheered and waved white kerchiefs in the air.

It was overwhelming. They couldn’t turn back.

Phase Two

Oshkosh was behind them, and phase two had begun. In phase two, they would fix problems and outfit the airplane with world-flight engines, avionics and other systems. They would test the airplane and then attempt the world flight.

After waiting several months for Teledyne Continental’s delivery of the IOL 200, they had a rollout in November 1985 to show off the new engines.

The composite construction gave Voyager resilience, but the wingtip movement was still a cause of concern. If out of control, it was extremely dangerous. The crew had noted that, while flying beyond 82 knots at heavier weights and while picking up thermals, Voyager picked up an oscillating pitch and wanted to porpoise. In an updraft, the wings bowed, the tips went up, and the wing roots went down, carrying the fuselage with them. That pitched up the nose and canard. The motion would repeat itself and magnify, unless the pilot or autopilot was able to stop the cycle. They could take it down to 82 knots when running into thermals, but to generate enough lift to sustain its weight, Voyager would have to fly above the critical speed. Leading the wave by 90 degrees controlled the porpoising, but the pilot would have to anticipate the cycle. For various reasons, Rutan would handle all the landings and takeoffs.

“The airplane turned out to be extremely difficult to fly, and, understandably, it turned out to be more than Jeana’s capability,” Rutan said. “I’d been flying all my life, and I was a test pilot. Her flight experience was very limited.”

Yeager, who had never handled Voyager above the dangerous weight, would need to take over if he was incapacitated. That meant Rutan would need to relinquish control, and let her gain some flying experience while he was in the off-duty position.

Details

They were beginning to have problems with cockpit noise. After just a few flights, Yeager noticed a ringing in her ears. They worked with the Bose Corporation, adapting experimental noise-defeating electronics. A sine wave generator registered the shape of sound waves and created waves that canceled them out.

Mission control, situated in a trailer beside Hangar 77, would help the crew on their journey. Larry Caskey, the mission control director, put together the communications and navigation team.

Rutan had spent weeks making avionics comparisons and decided that King Radio had the best and lightest components needed in just about every category. It was a pleasant surprise when Ed King, the owner of King Radio, called to offer sponsorship, while they were trying to figure out how to pitch the project to him.

For navigation, Rutan and Yeager relied on the King KNS 660 VLS Omega navigation system, supplemented by a satellite-linked global positioning system. In addition to the King KHF 990 HF and KX 165 VHF radios, they added UHF satellite communications. Radar was a King KWX 58.

The autopilot was a modified King KAP 150. Because of the flapping wings and longitudinal oscillations, a pitch stability augmentation system, a special rate gyroscope for the pitch control, assisted the autopilot.

Qualms

During one test, Rutan believed they were seconds away from a fatal fall. Bad pitching in the thermals required all the wit and determination he could muster, to get back to land. Yeager tried to sooth him, congratulating him for getting the beast under control.

But he insisted they had been seconds away from the wings snapping off. They had escaped the jaws of death—that time. He had had a premonition, and it hung on; this aircraft, this task, would kill him. It had to be faced: they risked their lives each time they took Voyager up.

Rutan thought Voyager was a beautiful, but inherently dangerous and unsafe aircraft. He knew that two “slightly crazy people” had accepted the challenge and would take her on an unforgettable trip around the globe. But afterwards, she should be retired forever.

Rutan, who had been so sure of himself and his flying skills, now forced himself to climb into the cockpit of his Long-EZ, clenched his teeth and told himself, “I love flying!!” Although he rebuilt his courage, his apprehension continued.

As time went on, Rutan and Yeager, “partners, in the air and on the ground,” began to realize that the partnership was easier in the air than it was on the ground. But it was far from smooth, even in the air.

Rutan stressed a need for her to train and work on her flying, so she spent several weeks in instrument and multiengine training with Beech in Wichita, Kansas. Others also urged Rutan to let his copilot get some training at heavier weights when Voyager porpoised.

Ahead of them lay a publicity trip, slightly shorter than around the world, but it was still daunting. To remain in the public eye, they planned to fly 11,000 miles, shooting for a closed-course, non-refueled, distance record.

They scheduled test flight number 46 for July 8, 1986. The flight of four and a half days would be in a circuit, from a point 20 miles off the California coast near San Luis Obispo to Stewart’s Point, a point at sea northwest of San Francisco. They hoped to break the closed-course distance record that a B-52H had set in 1962. It would take 20 laps.

Spectators lined the runway, as they took off. From the beginning, it was a rough flight. The autopilot computer was overheating, causing it to hunt up and down for the proper orientation. They would have to shut it off and let it cool for a few minutes. Flying without the autopilot increased the work load tenfold.

On the first lap, they did a series of performance tests. Flying at 15,000 feet, Rutan pushed both engines to full throttle, heading for maximum speed. They had reached 108 knots, when suddenly a whirr and heavy pressure was in the stick. Thinking the autopilot had run away, Rutan tried to disconnect it, but the stick continued shaking badly.

Yeager looked out the window and informed Rutan that the elevator was vibrating. They were experiencing flutter, the uncontrollable flapping of a control surface that can quickly tear an aileron or elevator loose from the airplane. When Rutan pulled both throttles back to idle and pulled the nose up, the flutter stopped. The elevators weren’t designed to withstand that kind of flutter, and they were lucky they didn’t completely lose a control surface.

Because the pitch control of the airplane was at first too sensitive, they had added an elevator trim tab, or antiservo tab. The small wing-like structure behind the canard had artificially given them more elevator. After further testing, they decided to add one on the opposite side.

The control surfaces had been balanced, so they shouldn’t have experienced flutter. But just before the coast flight, Evans had put some paint on the airplane. More ended up on the trailing than on the leading edge, unbalancing the tab. The tab had begun to flutter on the lap, as they were turning. At the bottom of the lap, the prop started running away.

At the bottom end of the first lap, the pilots noticed that the rpms were climbing. As the rear prop sped up, the prop pitch was going flat. A circuit breaker had blown, the engine was idling hard, and the prop was spinning out of control. The aircraft lost altitude due to the drag. Rutan tried to restart the front engine, knowing the useless back engine needed to be turned off. To stop the back engine, he needed to bring the aircraft to as high an angle as he dared.

The pitch of the propeller was completely flat now, and the prop was out of control. The back engine was at hard idle but running at the red line, over-revving. With no thrust, Rutan had to disconnect the autopilot and push the nose over to keep from stalling. As they went downhill, the back prop produced no thrust.

Yeager pulled out the checklist, and they began to go down the procedures to start the front engine. After turning over a few times, the engine caught. But, even at full power, they couldn’t maintain level flight with only the front engine.

Rutan remembered his brother telling him that it wasn’t possible to maintain level flight with the rear engine windmilling. Trying to fly with that spinning prop was like dragging a huge solid disc behind them. The slipstream of the front engine would run right into that rear prop and create all kinds of drag. A pilot would have to feather or stop the rear prop, in order to fly on the front engine.

They had to stop that back engine from windmilling. Rutan reached back to the aft engine mixture control and pulled it into idle cutoff, to shut off all the fuel. That had almost no effect. He had to reduce that slipstream. He pulled the throttle on the front engine back to idle, on the ragged edge of a stall, and slowly pulled the nose of the airplane up. They’d never tried to fly the airplane that slowly before. Finally, that rear prop slowed down and stopped windmilling.

Now they pushed the nose over again. With full power on the front, they leveled out, and the rear prop remained still. They thought of turning back to Mojave, but the airplane had too much fuel for a go-around if they had trouble landing. They no longer had the rear prop to reverse as a brake.

Santa Barbara was at least 40 minutes away. Rutan spotted Vandenberg Air Force Base, a restricted Pacific missile test range, which had a runway used only for the space shuttle. Vandenberg was a restricted area, but they had an emergency. They called the frequency for the Vandenberg tower

“We’ll help you all we can,” the tower said, “but first you have to say the magic word.”

Rutan barked, “Mayday, Mayday.”

They were cleared and landed in restricted area. They taxied Voyager to a hangar belonging to Air Sea Rescue. While troubleshooting, they discovered a dead electrical short and traced it to the prop motor.

After opening the housing, they found that the motor’s armature magnet, which adjusted the blade’s pitch, had fractured. The armature wire was in charred bits. The polarity had somehow reversed, and instead of reducing pitch, the motor had been increasing it. At high rpms, the centrifugal force had turned the setup backward.

Just before nightfall, Melvill and Evans arrived to access the damage. Rutan explained what had happened. The team tried to figure out what made an electric motor perform that way. Their best guess was that the vibration had been at fault, and that the prop must have been running at the specific frequency at which the magnet was sensitive.

Burt Rutan was more concerned about the flutter and the problem with the elevator. He decided the sparrow strainer should be modified. Evans thought the modification could be made at Vandenberg, but the designer wanted them to go back to Mojave and start all over again.

Voyager remained overnight at Vandenberg, and the team spent the night at a motel. Wednesday morning, Dick Rutan finished installing the new prop pitch control motor. He was sure the flutter wouldn’t recur if they kept their speed and altitude down. After waiting for fog to burn away, they finally took off at 3 o’clock, restarting the record flight from Vandenberg.

Again, the airplane oscillated as they got into the layer of turbulence. As soon as they climbed through the weather, it was perfectly smooth.

That day, they made one lap. On Thursday, Yeager got in the pilot seat, but soon discovered they were slowly rolling. They had inadvertently opened a circuit breaker and cut power to the main attitude indicator, and, deprived of power, the reference gyro was slowly spinning down. The autopilot was orienting them to a false horizon.

They turned off the autopilot, slowly brought the airplane back level, reestablished the attitude indicator and restarted the autopilot.

On the night of their final lap, the back engine started to run rough. The spark plugs were clogging. North of San Francisco, at the point of the course farthest from home, they started their turn. The engine shook, banged and nearly quit.

Rutan grabbed the prop controller, increased rpm, and pushed the throttle up to change the combustion swirl pattern and clear the plugs. The engine continued to shake and clunk for several minutes. Then it began to run clean.

Yeager and Rutan went over the checklist and restarted the front engine. They no longer felt they could run on low horsepower, or the plugs would clog again.

They had put the gear down above Tehachapi, and coming over the mountains, ran into some of the worst turbulence they had ever encountered. Finally, at 6:37 a.m., on July 15, they completed their mission. In 111 hours and 44 minutes, they’d traveled 11,857 statute miles, breaking the Air Force’s world distance record held for nearly 40 years.

As they landed, people shouted and champagne sprayed. But Yeager wasn’t up to celebrating. She had drunk less than a gallon of water during the flight, and dehydrated, she was led away from the press conference. Newspapers around the world featured pictures of the landing.

For the first time since World War II, an absolute, unlimited category aviation record had been established—not by an elaborately supported military effort, but by civilians. But would they be able to fly around the world?

Cont. in January…Voyager: A Crazy Dream? – Part II