By Deb Smith

Louise Thaden was the winner of the first Powder Puff Derby in 1929. Shortly after that race, women aviators joined together to form the Ninety-Nines.

Grounded in the early aviation pioneer spirit, the Ninety-Nines got their start back in the summer of 1929. That year, officials from the world-famous, male-only Cleveland Air Races finally gave in to pressure and established the first all women transcontinental air derby, from Santa Monica, Calif. to Cleveland, Ohio. Known as the Powder Puff Derby, the race required each pilot to hold 100 logged pilot hours and fly an aircraft with horse power “appropriate for a woman.”

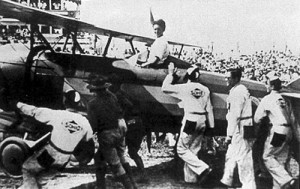

Forty female pilots qualified, and 19, including noted aviatrix Amelia Earhart, competed. Sixteen completed the race. The race originated in Santa Monica, Calif., and crossed several major cities. The first pilot to land in Cleveland was 23-year-old Louise Thaden.

For those who flew in it, the Women’s Air Derby was much more than just a “race for girls.” It was a major factor in opening up the skies to female pilots, and in doing so, it brought together a courageous collection of top female pilots that felt a need to codify this unique sisterhood.

After arriving in Cleveland, several pilots gathered under the grandstand, including Earhart, Gladys O’Donnell, Ruth Nichols, Blanche Noyes, Phoebe Omlie and Thaden. The pilots pondered the possibility of organizing themselves and other female pilots.

Clara (Studer) Trenckmann, not a pilot herself, but a strong believer of women in aviation, set the ball in motion. She worked at the Curtiss Flying Service and was the editor of the company’s newsletter. On Oct. 1, 1929, she asked Curtiss executives to allow four Curtiss demonstration pilots, Fay Gillis, Neva Paris, Frances Harrell and Margery Brown to draft a letter to all licensed women pilots inviting them to a meeting at Curtiss Field, in Valley Stream, Long Island. The letter asked, “Could you attend an organization meeting on Nov. 2, 1929, around three o’clock in the afternoon, at Curtiss Field, Valley Stream, Long Island?”

According to Kathleen Brooks Pazmany, the author of “United States Women in Aviation 1919-1929,” published by the Smithsonian Institute Press, 26 women attended and 31 sent regrets. Because of poor weather, only four women flew in; another 22 arrived by train.

Trenckmann provided an invaluable service. She handled the responses, arranged for the meeting place, and provided the food and transportation for the out of town pilots. She converted conversation into action.

The women were concerned about the poor showing, and disappointed until they discovered they didn’t have a complete list of names. Paris and Earhart drafted a second letter, this time to include all those who had been missed in the first mailing. A letter went to 126 women, inviting them to meet at Opal Kunz’ home in New York City, on Dec. 14, 1929.

These East Coast pilots were practical. They weren’t looking for fame or fortune—simply a little esprit de corps among their sister flyers. And they were adamant that the organization not be a maze of confusing rules and procedures.

“It need not be a tremendously official sort of organization, just a way to get acquainted to discuss the prospect for women pilots, from a both a sports and breadwinning sort of view,” they explained in the letter.

The organization wouldn’t have a lot of officers or useless red tape, but it would have “a little constitution, brief, simple, and not too ironclad.”

Their boardroom was an active, noisy Curtiss maintenance hangar—complete with complementary live engine run-ups. With a toolbox wagon for a tea cart, the ladies quickly went about the business of determining membership eligibility and group purpose. With membership open to any woman pilot with a license in good standing, the organization would strive to provide “good fellowship, jobs and a central office and files on women in aviation.”

But, what would they call themselves? Suggestions included the Climbing Vines, Noisy Birdwomen, Homing Pigeons and Gadflies. Jean Davis Hoyt and Earhart suggested naming the group after the number of women at the meeting, and those who didn’t attend, but wrote, telephoned or telegraphed their interest in joining. The total came to 99 names, so the Ninety Nines became their official name, based on the sum of those original charter members. Membership was immediately opened to other women as they became licensed pilots.

They agreed to hold elections, with Paris coordinating them, but she died in an air accident en route to an air race in Florida. The club remained unstructured while Thaden served as secretary. In 1931, the group voted Amelia Earhart as the Ninety Nines’ president.