By Larry W. Bledsoe

On December 5, at the San Diego Aerospace Museum, the Southern California Friends of the American Fighter Aces Association held a symposium to pay homage to Medal of Honor recipients.

The men present came from different branches of the service and fought in different wars, but they had one thing in common. They were all recipients of the Medal of Honor, which is the highest distinction that can be earned by a member of the Armed Services of the United States. The president, in the name of Congress, awards it to an individual who while serving in the Armed Forces “distinguished himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

These men aren’t supermen, but ordinary people like you and me who have done extraordinary things in perilous times.

The moderator for the symposium was Barrett Tillman, well-known author of many books on aviation history, including one of his most recent works, “Above and Beyond: The Aviation Medals of Honor.” He began by giving a history of this prestigious honor from its first issue in the Civil War to the present. Then he introduced the five Medal of Honor recipients who had graciously agreed to speak at the symposium.

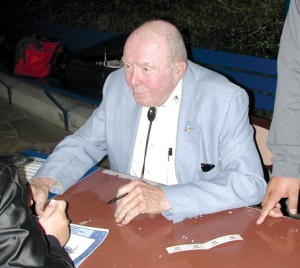

Col. James Swett

Col. James Swett, a Marine Corps pilot during World War II, shared with the audience a humorous incident about his first flight, which was in a hot air balloon at a county fair. Then he told briefly about his flight training before getting into his experiences in the South Pacific.

Swett arrived in Guadalcanal in late January 1943, and flew a Wildcat with VMF-221. Most of their combat missions were to provide bomber escort against Japanese targets, but it was his action on April 7, 1943, for which he received the Medal of Honor.

That morning, after returning from an uneventful patrol, Swett was sent to intercept Japanese dive bombers that had been spotted by a coast watcher heading for the harbor at Tulagi, where several U.S. naval vessels were anchored.

Upon arriving at the scene, his flight found themselves greatly outnumbered by a large group of Japanese dive bombers and fighters. While the Japanese fighters were engaging the rest of his flight, Swett went after the Val dive bombers. He caught up with the formation and proceeded to dispatch one, and then another. He followed them into their dive on the American ships below while blasting more out of the sky. He was so close to the enemy formation that his own plane got hit by friendly fire.

After pulling out of the dive, he went after other dive bombers. He had dispatched seven enemy planes in a short period; as he closed in on the eighth dive bomber, its rear gunner opened fire on him, hitting the Wildcat’s oil cooler and shattering its windshield. Swett empty his guns into the enemy plane before ditching his Wildcat in the water. He never got credit for the eighth enemy aircraft, even though it was found where he said it would be.

Later, his squadron transitioned to the Corsair, and he told about something that happened then. There was an emergency landing strip in the Russell Islands where a Seabee outfit was based. One of the Seabees had sort of accidentally hit a cow with a tractor and killed it. As a result, they ended up having the rare treat of hamburger. In addition, since they also had a refrigeration unit, they had ice cream.

As soon as word got out that pilots making emergency landings at the strip were treated to hamburgers and milkshakes, there was a rash of emergency landings. When the CO found out what was happening, he put a stop to the so-called emergency landings.

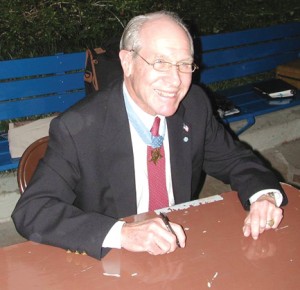

Capt. Thomas Hudner Jr.

Navy Capt. Thomas Hudner Jr., a Corsair pilot, received his MOH for heroic action during the Korean War.

Navy Capt. Thomas Hudner Jr. was also a Corsair pilot, but in a different war. It was for his action shortly after the Korean War started that he received the MOH.

On June 26, 1950, North Koreans crossed the line and invaded South Korea. Hudner’s squadron was in the Mediterranean at the time and was aboard the carrier “USS Leyte” off the coast of Italy when they got orders to go to Korea. They returned first to the States to pick up new planes before heading for Korea via the Panama Canal.

They started flying close air support missions in October 1950 from the “USS Leyte,” which was one of two carriers with Task Force 77 operating off the coast of Korea. By the end of November, MacArthur’s forces had pushed all the way to the Yalu River, which is on the border of North Korea and Manchuria. Then an unexpected mass of Chinese troops poured over the border, encircling our troops at the Chosin Reservoir. The Marines found themselves embroiled in a bloody fight for survival in sub-zero weather as they fought their way along a narrow dirt road to the port of Hungnam where they were to be evacuated.

On December 4, Hudner, Jesse Leroy Brown and four other Corsair pilots from VF-32 took off from their carrier on a ground support mission for the beleaguered Marines. Over hostile territory, Brown’s plane took a hit from ground fire and he crash-landed on the only open spot he could find on the slope of the tree-covered mountainous terrain. Brown survived the crash, but was trapped in the cockpit. The engine had separated from the plane, but a fire smoldering near the gas tank just ahead of the trapped pilot threatened to engulf him in flames at any moment.

Hudner knew he could end up trapped in his plane like Brown, but also knew Brown needed help right then if he was to survive, so he crash-landed his Corsair nearby and went to Brown’s rescue. Unable to free Brown from the wreckage, he then tried unsuccessfully to put the fire out by packing snow on the smoldering fuselage. In the meantime, their squadron mates were flying cover and a helicopter had been called in. Unfortunately, neither Hudner nor the helicopter pilot was able to free Brown from the wreckage before he died.

The incredible life story of Ensign Brown, who happened to be the Navy’s first black pilot to fly a Navy fighter, and this daring rescue attempt are told in the interesting book “The Flight of Jesse Leroy Brown,” by Theodore Taylor.

Col. Leo Thorsness

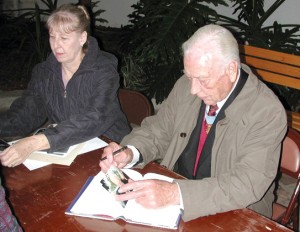

Col. James Swett, a Marine Corps pilot during World War II, received the Medal of Honor for action on April 7, 1943.

Col. Leo Thorsness, an F-105 Thunderchief pilot in Vietnam, told about one of his surface-to-air missile suppression missions over North Vietnam. He said his flight of four would go in on a target from 20,000 feet. Whenever the SAMs came up, they would dive for the deck with afterburners going. This would cause the SAMs coming after them to head down.

At the last possible second, they would cut their afterburners and pull out. The SAMs couldn’t respond as fast and would hit the ground. This maneuver worked for him on 14 missions.

He received the Medal of Honor for his actions on a SAM suppression mission on April 19, 1967. Thorsness and his wingman had taken out two missile sites when his wingman was hit by anti-aircraft fire. Thorsness circled his downed friend and called in search and rescue. A MiG-17 showed up and Thorsness dispatched it before leaving the area for an aerial tanker due to low fuel.

Before finding one, he received word that more MiGs were threatening the helicopters trying to save his wingman. Returning to the spot, he found four MiGs, which he went after. He damaged one and chased the others off the rescue scene. His fuel supply then critical, he was forced to find a tanker. Upon hearing another flight was in danger of going down due to lack of fuel, Thorsness let them use the tanker, and instead headed for a forward operating base.

SAM suppression missions were always dangerous; as a result, he later ended up a POW. He said the first three years was brutal and the last three years were boring. He also said the North Vietnamese interrogators weren’t after military secrets, but were looking for statements they could use for propaganda purposes. The interrogators often showed them reports about what the anti-war demonstrators were doing and saying in the U.S.

Thorsness said what made the difference in their treatment was a little known letter-writing campaign by Americans to the North Vietnamese condemning them for the harsh treatment of the POWs. He went on to explain that an important part of survival was communications between the POWs. Since they weren’t allowed to talk to each other, they developed tap code communications.

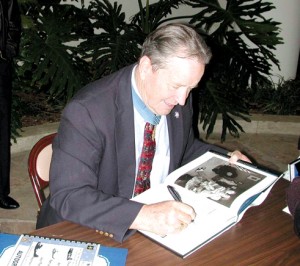

Maj. Gen. Patrick H. Brady

Maj. Gen. Patrick H. Brady, a Huey ambulance helicopter pilot in Vietnam, received the MOH for his action during the Tet Offensive on Jan. 6, 1968.

Maj. Gen. Patrick H. Brady, a Huey ambulance helicopter pilot in Vietnam, received the MOH for his action during the Tet Offensive on Jan. 6, 1968. He shared with the group how he developed the piloting skills needed that day near Chu Lai.

His squadron picked up wounded, day and night, in all kinds of terrain and weather. When it was possible, they’d scope out the best approach to the pickup point and then follow rivers, ravine or whatever natural barriers they could find to hide themselves from enemy fire on the way to the pickup point. Once there, they’d turn the tail of the Huey towards the enemy fire. This would give them very limited protection, but it was the only protection they had. They kept moving as much as possible, because a moving target was harder to hit. Their call sign was “Dust Off.”

During his first tour of duty, Brady was assigned to the Delta area, where it was flat and you could set down almost anywhere. His second tour of duty was quite different. He arrived with mostly new aviators and none of them had been trained for the mountainous terrain. They flew day and night in all kinds of weather. Often, clouds hid the mountain tops or fog in the valleys and ravines obscured the pickup points.

On one mission, he was to pick up a soldier suffering from a snake bite, who was on a hilltop obscured by clouds. Brady found his way to the valley next to the mountain and tried to go up the side of the mountain to the pickup point. When he got in the clouds, he became spatially disoriented and dropped back down. He tried again several more times with the same results. Then he discovered that by staying close to the mountain he could see his prop tip and a treetop. By having those two points of reference, he could fly up the side of the mountain without becoming spatially disoriented.

One night during a tropical storm, they had to make a pickup in a cloud-shrouded valley. He remembered what the silhouette of two mountains looked like and asked the troops on the ground to let him know when he was directly overhead. Then he asked them to fire a flare, which he would follow down to the pickup point.

On Jan. 6, 1968, according to his citation, he was called upon to pick up wounded in fog-covered areas in the face of enemy fire. At one location, he made four trips to pick up wounded where two other aircraft had been shot down earlier in the day while making unsuccessful attempts to land. He was then called to evacuate some American soldiers trapped in a minefield. Throughout that day, due to battle damage, Brady utilized three helicopters to evacuate a total of 51 seriously wounded men, many who would have perished without prompt medical treatment.

During his second tour of duty, totaling nine and a half month, his unit, with six helicopters and 40 crewmembers, made 21,000 evacuations. During that time, 23 of their crewmembers were wounded in action, including two injured by an exploding mine the day he evacuated men out of the mine field. Only three of the helicopters would be available at a time; the other three would be down for repair or maintenance. They would fly missions day and night in all kinds of weather, often making 24 to 30 missions a day.

SSgt. Walter D. Ehlers

Staff Sergeant Walter D. Ehlers, the only non-pilot MOH recipient at the symposium, provided an insight into combat as seen by the soldier on the ground.

Staff Sergeant Walter D. Ehlers, the only non-pilot MOH recipient at the symposium, provided an insight into combat as seen by the soldier on the ground.

Ehlers joined the U.S. Army in 1940 and served in North Africa before hitting the Normandy beaches on D-Day. A few days later, June 9-10, 1944, during the fighting in the hedgerows near Goville, he found himself in the situations that resulted in his receiving the MOH.

According to his citation, Ehlers “repeatedly led his men against heavily defended enemy strong points exposing himself to deadly hostile fire.”

“Without waiting for an order, Sergeant Ehlers, far ahead of his men, led his squad against a strongly defended enemy strong point, personally killing four of an enemy patrol who attacked him en route,” the citation continued. “Then crawling forward under withering machine-gun fire, he pounced upon the gun-crew and put it out of action. Turning his attention to two mortars protected by a crossfire of two machine guns, Ehlers led his men through this hail of bullets to kill or put to flight the enemy of the mortar section, killing three men himself.

“After mopping up the mortar positions, he again advanced on a machine gun, his progress effectively covered by his squad. When he was almost on top of the gun, he leaped to his feet, and although greatly outnumbered, knocked out the position single-handed.”

The next day, having advanced deep into enemy territory, Ehlers’ platoon found itself “in an untenable position as the enemy brought increasing mortar, machine-gun and small-arms fire to bear on it,” and was ordered to withdraw. After his squad had covered the withdrawal of the remainder of the platoon, Ehlers stood up and “by continuous fire at the semicircle of enemy placements, diverted the bulk of the heavy hostile fire on himself, thus permitting the members of his own squad to withdraw.”

“At this point, though wounded himself, he carried his wounded automatic rifleman to safety and returned fearlessly over the shell-swept field to retrieve the automatic rifle he was unable to carry previously,” said the citation. “After having his wound treated, he refused to be evacuated, and returned to lead his squad…”

During the meeting, someone said that the one characteristic these gentlemen all have in common is that they never gave up. The next time you hear the “Star Spangled Banner,” remember this is “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” thanks to brave men such as these that have made it possible for all of us to be free.