Aviator and philanthropist Michael Leeds has taken a hands-on interest in teaching future generations about social responsibility and ethics.

By S. Clayton Moore

Michael Leeds puts his money where his mouth is. Leeds, 53, has evolved over the years to become a business leader, an aviator and one of the country’s most remarkable philanthropists. After building up his parents’ small New York company, CMP Media, into a publishing juggernaut, he led his family in giving a $35 million gift to the University of Colorado’s business school, the sixth largest commitment to a business school in the country’s history.

The ultimate goal of this gift is to continue the legacy of the Leeds family. Leeds, his parents and siblings have all made the effort to elevate both business and society through their efforts. While their contributions range from gifts to leading educational organizations to anonymous donations to charitable organizations, they all tend to focus on ethical and social responsibility, a subject that has grown increasingly close to Leeds’ heart.

Leeds has been taught his spirited sense of right and wrong from a very young age. As he’s grown older and wiser, he’s stuck to those principles, having figured out long ago that the best way to profit in the long run was simple–to do the right thing, no matter what the cost.

Modest beginnings

Michael Leeds was born in 1952 in Great Neck, N.Y., and grew up on Long Island. His parents, Gerry and Lilo Leeds, were born in Germany prior to World War II, but their parents, members of the Jewish faith, fled to America as the Nazi Party began to rise in the late 1930s.

“They really are extraordinary people,” Leeds said of his parents. “These days, I’m old enough to recognize how they taught all of us to help the community.”

As a child, his parents always placed great emphasis on the importance of giving and education. When Leeds and his four siblings were children, they gave part of their allowance to charity, starting a lifetime of giving back to the community.

“One thing that has always driven them to get involved and work in the community is that even though they came to America as immigrants, they were educated,” Leeds explained. “They weren’t able to bring much here, of course, but they were able to transport their education, so to speak.”

In 1970, he graduated from high school and went off to look at colleges in Wisconsin, Michigan and Colorado, all of which had accepted him for enrollment. He and his brother, Richard, drove into Boulder in the middle of a dark February night.

“We got up in the morning and saw the sun shining on the Flatirons,” Leeds remembered. “It was sunny and beautiful; I looked at Richard and said, ‘I’m going here.’ He said, ‘Me too.’ So in 1970, I came to Colorado and Richard followed a year later.”

Leeds’ interests are many and varied even today, so it’s no surprise to learn that he bounced between majors, starting out in engineering like his father and later trying pre-med and finally deciding on business in his third year.

Taking flight

Michael Leeds, far right, leads a discussion on ethical challenges at the first annual Japha Ethics Symposium at the University of Colorado in 2003.

Leeds also finally got the chance to fly. He’d been interested in aviation ever since he saw the television program “Ripcord” (a parachuting drama that ran from 1962 to 1964). During his second year at CU, Leeds, his brother and a roommate went skydiving for the first time. Leeds started flying lessons soon after.

“I stayed and worked construction, so I had $700 burning a hole in my pocket,” Leeds laughed. “I saw something about a free introductory flying lesson, so I hitchhiked down to Jefferson County Airport and took a lesson.”

Leeds loved flying. He scraped through his lessons on an hour-by-hour basis, coming up with the money for lessons by working at a local restaurant and finally completing his check ride.

“Much to my surprise, the examiner said I did a good job,” Leeds said. “He told me I had earned a ‘license to learn.’ I’ve always remembered that moment and enjoyed learning more and more about flying over the past 30 years.”

Meanwhile, his parents were busy with a project of their own. In 1971, they founded CMP Media, a small publishing company based in Manhasset, N.Y. The company printed newspapers and magazines focused on high technology. They built the company with the determination to give employees a great place to work and to give customers a great place to do business. The Leeds children were involved from the very beginning.

“I came home from my freshman year in Boulder, kissed my mother hello, and went off to a nearby printing plant to help put out the first issue of our first newspaper,” Leeds remembered.

He worked summers at CMP before graduating from CU with his BS in business administration in 1974. Following graduation, he got his instructor’s license and taught flying. He also worked for the U.S. Parachute Association, completing over 550 jumps, and edited Parachute Magazine for two years. Later, he worked for Harcourt Brace Jovanovich and Ziff Davis Publications, where he met his future wife, Andrea Eisinger. She had been the human resources director responsible for his hire.

Good company

In addition to leading significant financial gifts to the University of Colorado, Michael Leeds often stops by the school to speak with students.

Leeds joined his parents at CMP in 1984, starting a profitable travel division that was sold off in 1994. He was instrumental in driving the direction of the company, helping his parents write a set of seven operating principles during a time when many short-sighted corporations were centered purely on profit.

“We lived by those principles,” Leeds affirmed. “A lot of companies write these kinds of documents today, but I think we were one of the few who really made our decisions according to those ideas. There were times we felt pressure as an organization, of course, but we always tried to avoid those shortcuts.”

In 1988, Gerry and Lilo Leeds asked Michael to take over the company so they could pursue their own humanitarian interests, primarily the challenge of encouraging troubled children in urban and rural areas to succeed academically, finish school and go on to college.

“The company was successful even then,” Leeds remembered. “They wanted the opportunity to start working in the community and giving back to the country where they experienced so much success.”

The young business leader had quite a heavy load to carry. By the time Leeds became president, and subsequently CEO, CMP Media had just hit $100 million in sales and had over 1,000 employees. The company owned many of the most important names in computer print publishing, including Information Week and Windows Magazine.

“It was a lot of stress, partly because my parents had run the organization very personally,” he admitted. “They really were true entrepreneurs and had handled everything on a one-on-one basis. The really important thing was to start putting my own management team in place. There were so many requests coming at the two of them that it would have been impossible for me to run it alone.”

To prepare, Leeds enrolled in Executive Program and Organizational Change, a management program at Stanford University. He also began to forge a new executive management team that included a new chief financial officer, human resources division and general counsel. On July 4, 1988, a date he calls his “very own independence day,” he became CEO of the company.

While the structure may have changed, the atmosphere didn’t. Leeds continued making decisions about CMP with the same compassionate heart his parents had used when starting the company.

“CMP demonstrates that socially responsible business practices aren’t a hindrance in making money,” Gerry Leeds observed. “We got and retained customers because we had good customer service and were a good company to do business with.”

There were plenty of innovative leadership strategies, but the aspects that Leeds remembers are the little things that satisfied employees. CMP had licensed on-site daycare years before such benefits were typical in the industry. Two prime salespeople who had children were allowed to split a job, and produced better market share in the process. Through a committee, CMP’s employees were also allowed to select their own benefits.

“You let the employees come up with an answer and they’ll do just fine,” Leeds said. “What I need or want isn’t always relevant to the needs of those other 2,000 employees. The great thing is that you can ask people what they need. If you just listen, you can often provide the solution for them quite easily.”

Leeds emphasized that those novel ideas all helped, and did not hinder, the company’s success.

“There are lots of ways to make a good company and they ultimately make those companies more profitable,” Leeds said. “There’s a lot of discussion about social responsibility and diversity and a lot of people like to posture that it’s something you should do because it’s right, even if it costs money for the company. That’s simply not true. The fact is that social responsibility increases profits for a company, and you do these things to improve the company’s performance. It just happens that it’s also good for society.”

Under Leeds’ leadership, the company was selected as one of Fortune Magazine’s “100 Best Companies to Work For,” and Working Women Magazine’s “100 Best Companies.”

“The biggest award I ever got was that Fortune named us one of the best companies to work for,” Leeds said. “I always thought that was very important and that it was a real credit to us as a company. I always said that people at CMP worked hard because they wanted to, not because they had to, and it’s one of the main reasons we were successful.”

CMP certainly didn’t suffer because of its ethical stance. Leeds took the company public in 1997 and by the beginning of 1999, CMP was producing nearly $500 million in sales annually and had 2,000 employees.

“Taking care of your people and the community around you creates tremendous loyalty–and it makes a fun working environment,” Leeds said.

In June 1999, the Leeds family sold CMP Media to the UK-based United News and Media for $940 million. Leeds and his family were also remarkably loyal to the employees who helped them build up CMP’s remarkable success. On the back side of the company’s sale, the Leeds family gave $50 million back to their employees.

A model school

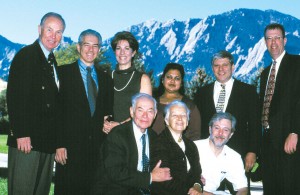

The Leeds family gathered to celebrate the launch of the Leeds School of Business. Back row, L to R: Richard Byyny, Michael Leeds, Andrea Leeds, Sunita Leeds, Dan Leeds and Steve Manaster. Front row, L to R: Gerard Leeds, Lilo Leeds and Richard Leeds.

Since the sale of the company, Leeds has kept busy.

“I still have a lot of different interests,” he said. “When you have the kids and you have the community, there are plenty of things to keep up with. That was the nice thing once I sold the business. Some people aren’t sure what to do when they leave a company. I had lots of things I wanted to do.”

His first priority, beyond spending time with his wife and three daughters, was to return to flying. Encouraged by his wife return to something he felt strongly about, Leeds bought a Falcon 50 and formed a small company, Flightstar, Inc., as a mechanism through which he could fly, pilot charter flights and consult with aircraft management companies. Today, he serves as vice president of sales and marketing for Executive Fliteways, a major Long Island jet charter and management company.

“I have a great relationship with Executive Fliteways,” Leeds said. “I really enjoy flying with them, and every time I make progress, I’m very proud of it. They have a first-class operation focused on safety and good management.”

Leeds also said that the company manages their employees with the same care he used when managing CMP.

“I’m really focused on how they treat their people because it’s something near and dear to my heart,” Leeds said. “Through the ups and downs of the aviation business cycle, they’ve really taken care of their employees, which is terrific.”

He also began working extensively with his old alma mater, the University of Colorado, where he says he spent some of the best years of his life. He had always kept in contact with faculty and staff and had been a speaker at the school’s graduation ceremonies. As a member of the university’s Business Advisory Council, he became aware of a higher need within CU’s business school.

“Being involved with the BAC allowed me to understand the deep commitment of the faculty and BAC members to social responsibility and diversity,” Leeds recalled.

He started having serious conversations with the school’s dean, Steve Manaster, who shared Leeds’ commitment to values and ethics.

The outgoing dean of the Leeds School of Business, Steve Manaster, was instrumental in focusing CU’s use of the Leeds’ $25 million gift.

“I was impressed by Steve’s focus on moving the business school into the top 25 in the country,” Leeds remembered. “One thing led to another and through our discussions, it emerged that they were willing to put a greater emphasis on social responsibility and ethics as part of the curriculum. It was a good match for what we wanted to contribute.”

In 2001, Leeds approached his family, who were enthusiastic about helping shape the business leaders of tomorrow through a major donation to the school. Richard Leeds, who graduated in 1975, and his wife Anne Kroeker, Dan and Sunita Leeds, and parents Lilo and Gerry Leeds all contributed to the $35 million gift, the largest private non-corporate commitment ever received by the university.

“I’m very enthusiastic about it because they believe in so many of the same principles that we do,” said Lilo Leeds. “We’ve been very fortunate that our businesses did so well and that’s why it’s important for us to give back.”

It gave Michael Leeds a tool by which he could continue to demonstrate that corporate ethics are a good and profitable idea.

“I felt that it would be great to find a way to educate people according to that model,” he remembered. “When I was running the company, I could hold up CMP as an example to show people that they could be successful and still be a socially responsible company in all aspects. In many ways, the school serves that same purpose.”

In recognition of the Leeds family’s gift, the business school was renamed the Leeds School of Business. Richard Leeds was initially uneasy about the public nature of the commitment, but his brother observed that naming the school is an important symbol.

“I think philosophically that when you contribute in this manner and also put your name on it, you’re taking a stand on what’s important,” he said. “The Leeds School of Business is going to stand as an organization that is for social responsibility and ethics in business, the very same values that made us successful at CMP. Ultimately, it has a permanence of position and structure that will last into perpetuity.”

Steve Manaster, who was replaced this year by Dennis Ahlburg, incoming dean, says the Leeds name carries a lot of weight in the competitive academic community.

“The name gives the school notoriety and will cause people to look more closely at what a good school we really are,” Manaster said. “And they will like what they see, which advances our reputation in the world. Resources from the Leeds gifts allow investments in our school, which is an even better increase beyond our reputation.”

The shift in the school’s direction came at an interesting time for the country’s business community.

“It’s timely, isn’t it?” Leeds said. “We got more deeply involved with the school and shortly after, Enron’s nonsense rose to the surface. The school has its challenges, of course, but I was happy to see one of our professors win a Nobel Prize. At the same time, CU has dropped off the list of top party schools. We’re going the right way in both directions.”

Leeds continues to be involved with the school’s continuing development, speaking once or twice a year to the student body and visiting the school on a regular basis. He now serves as chairman of the school’s BAC.

“Evolution is a good term for the school,” he observed. “There’s a cycle and a rhythm to the school and it takes time to institutionalize programs. In the end though, the whole program is about the students. I love talking to the students and I stay in contact with them. It’s really worked out great.”

His efforts extend to other arenas as well. Leeds is a trustee of the North Short Long Island Jewish Hospital System, one of the largest healthcare systems in the world. He’s also a director of the Institute for Student Achievement, an organization started by his parents to advocate educational opportunities for at-risk youth.

Michael Leeds and his family have truly been architects of American society, using their success not simply for personal gain but also to make things better, all by sticking to their original principles.

“I think you have to be very rigid about integrity and honesty,” Leeds said. “It’s the foundation of all business and it needs to be emphasized over and over again. It’s the prerequisite to building anything good.”

For more information about the Leeds School of Business, visit leeds.colorado.edu. For more information about Executive Fliteways, visit [http://www.fly-efi.com].

- Michael Leeds and his wife Andrea met during a job interview. She was a human resources director and he was an aspiring advertising salesman.

- Michael Leeds’ Falcon 50 has been repainted, refurbished

- Michael Leeds helps technicians at Garrett Aviation Services untangle the complicated wires behind his new avionics.

- Jim Tomaszewsk and Mike Leavy taught Michael Leeds much of what he knows about flying.

- Michael Leeds, a frequent visitor to the business school in Colorado bearing his family name, waves from the window of his Falcon 50.